| Discover the Reality of Scientific Mythology The Facts of Self-Animating Networks in Nature and a New, Realistic Role for the Mythic Imagination

|  |

> NOTICE: This website is represents a work-in-progress. Please contribute your feedback! email link <

| Home Page | Applying Scientific Mythology |

|

|

Perceiving Hidden Dynamics and Mysterious Agency in Self, Society, and Nature--through Factual Symbolism Bottom Line:

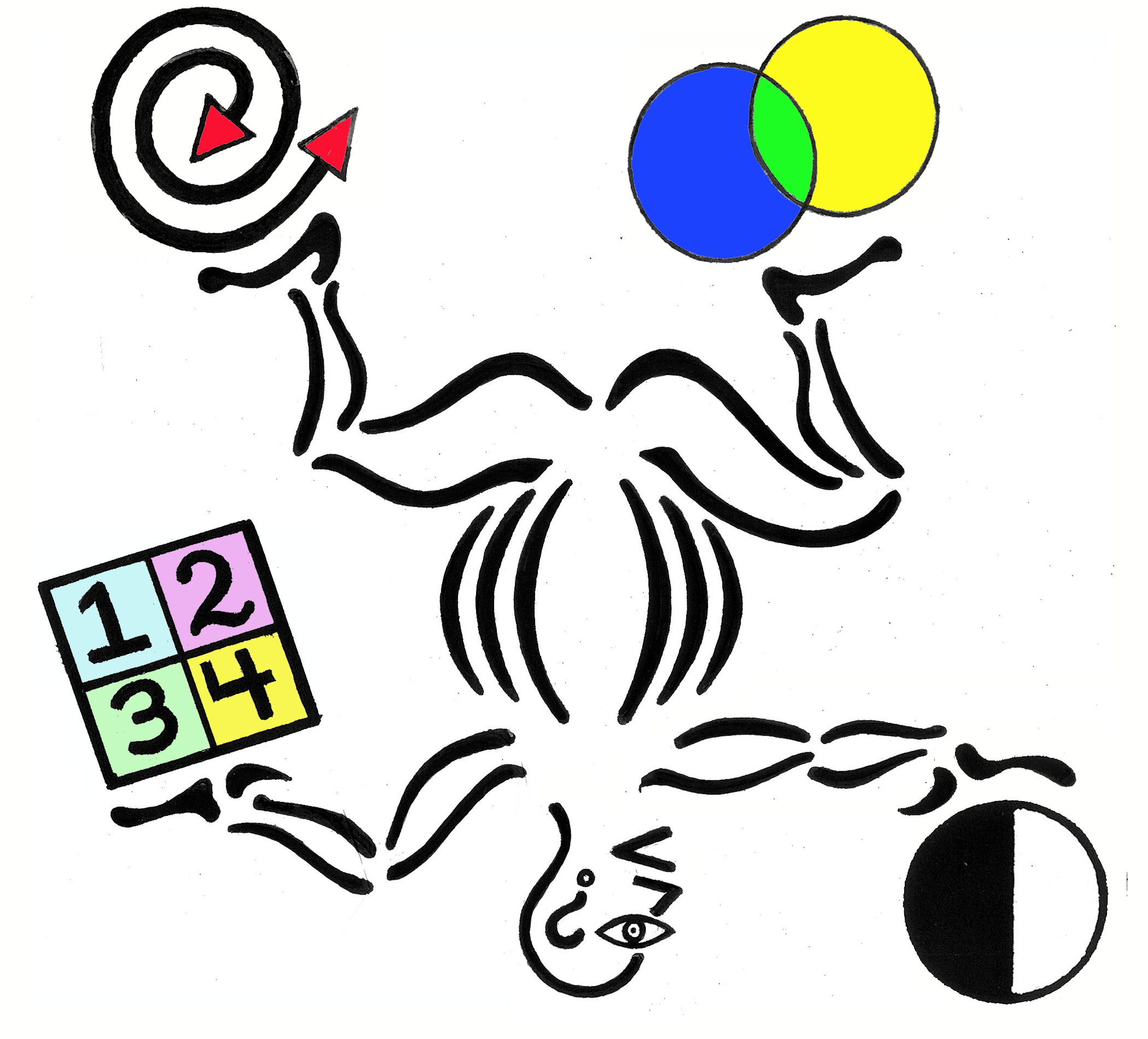

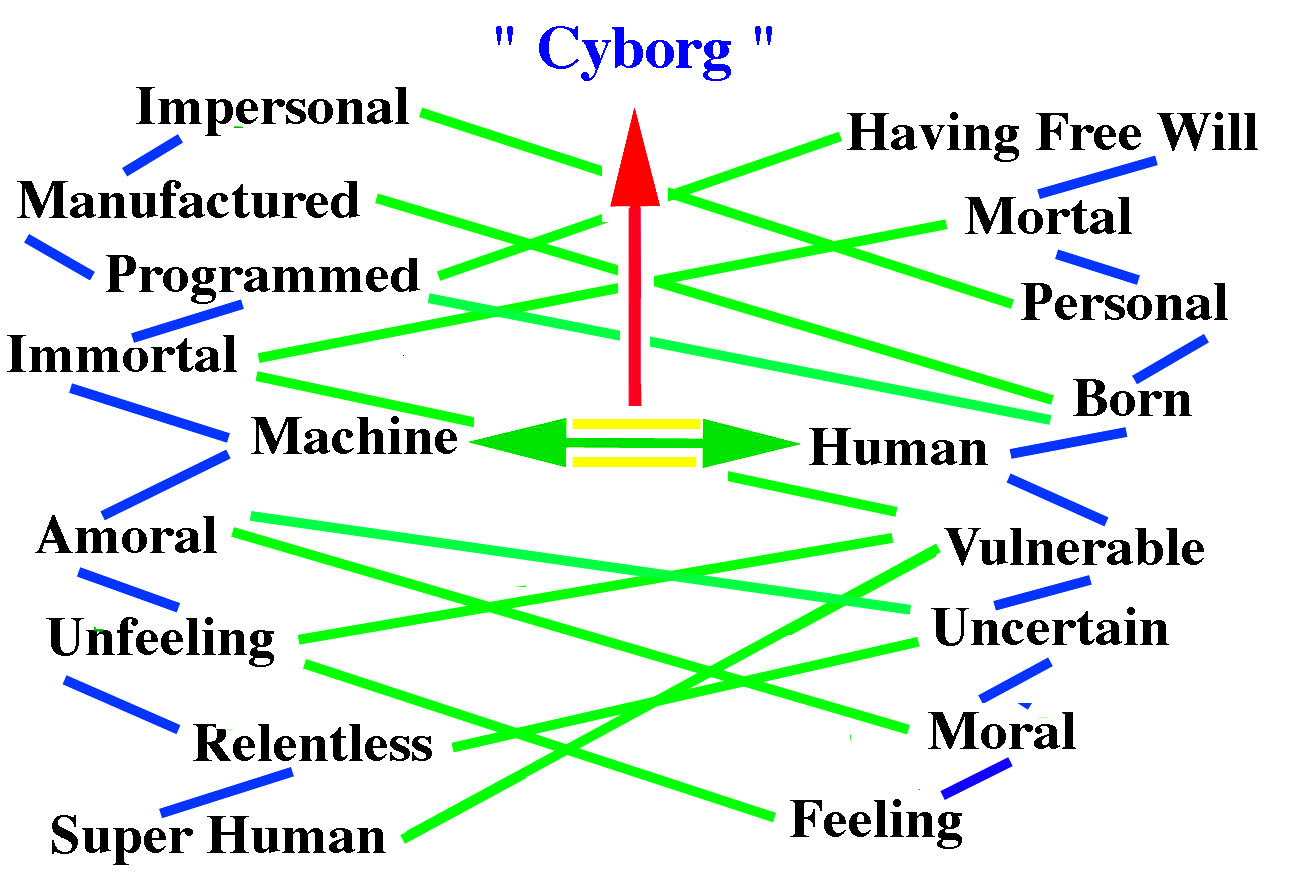

1. Network Analysis--a subject is analyzed as an interactive network: Any topic or context can be plotted as a constellation of parts and relationships. The resulting network is then examined for feedback loops and how they reinforce or retard network behaviors. These interdependencies can then be examined for the emergence of overall network autonomy and its intentionality. This analysis enables archetypal description of the qualities of network operations and their psychological character. 3. Symbolic Elaboration--the revealed network traits are symbolized: The insights gained from network analysis is elaborated through symbolic modeling, using references from traditional mythologies, art, literature, popular culture, and spontaneous imagninal improvisations in the moment. That symbolic elaboration can then be used to enact symbolic gestures of interaction with the network as an intentional entity. 3. Practical Incorporation--analytical and symbolic insights are related to our behaviors: The perspectives and experience gained from network analysis and its symbolic elaboration are explored in relation to real world contexts. Pragmatic attitudes and efforts to interact with the subject network are re-configured in more realistic ways. |

|

> Summary Overview <

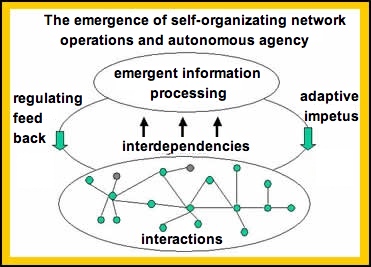

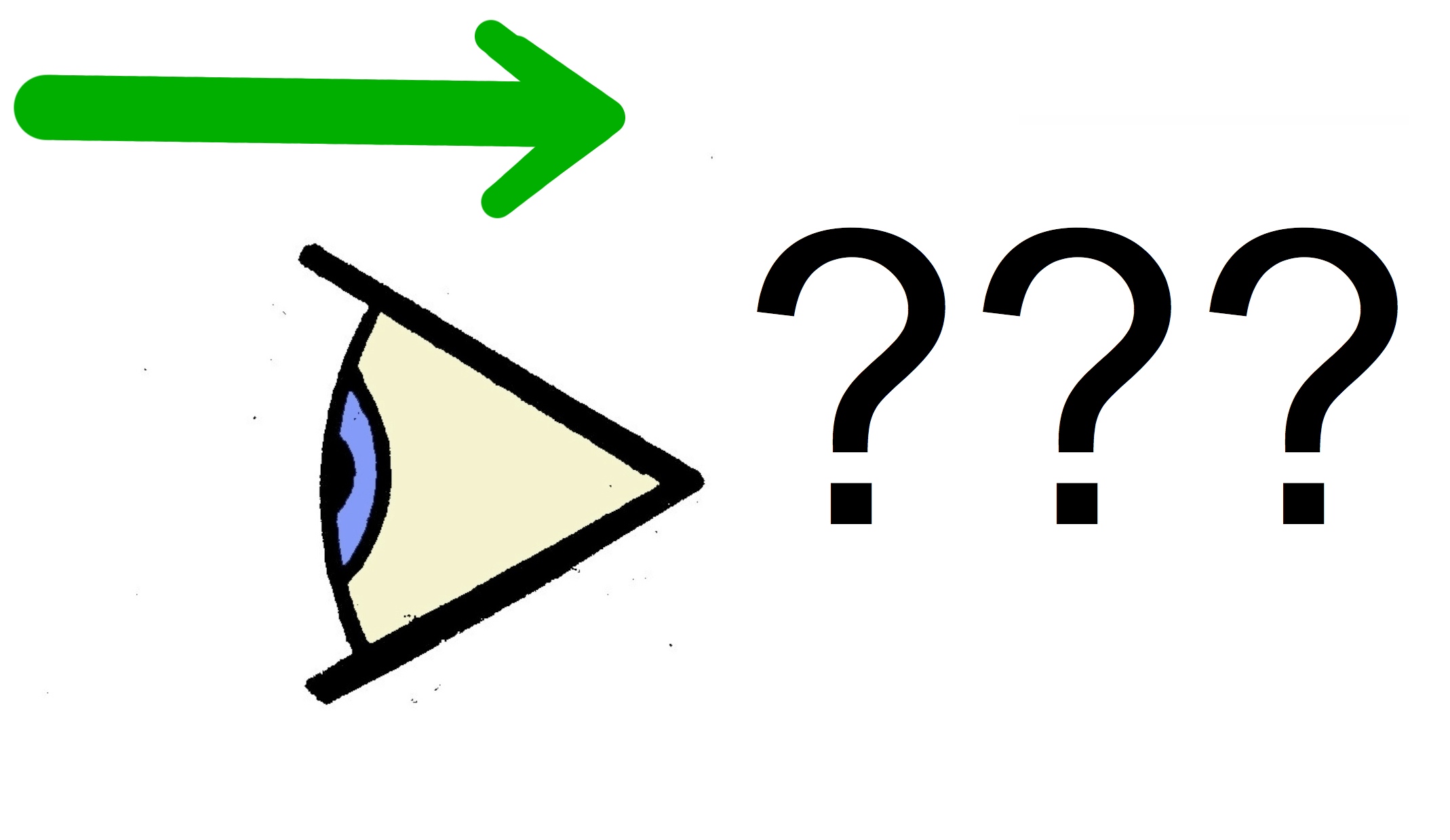

Practicing Scientific Mythology Interacting with Emergent Ordering and Self-Animating Systems through Network Constellation, Archetypal Analysis, and Symbolic Elaboration To be scientifically mytho-logical is to be archaic and modern all at once. The science "sees" evidence for emergent order creation and autonomous system networks. The mythology "sees" these as intentional spiritual animators of the world. Though science provides the initiating basis for practicing Scientific Mythology, this is not technical science. Rather, it is the practice of engaging the basic insights of the science through the mythical imagination. The resulting symbolism helps us better comprehend what the science reveals but cannot be fully explain. The new scientific insights about emergent order creation and autonomously self-animating networks are so profoundly strange to our familiar sense of scientific reality, we require additional methods for appreciating them. What science now reveals about complex dynamics is indeed what mythic symbolism always served to make tangible. Like the new science of complexity, mythic imagination does not tell us "what" exactly makes most of the order in the world, but about how what exits gets ordered--through the synergistic emergence of self-organizing criticality. Neither can tell us "what is right to think" or "how to make things happen" predictably. Rather, both can re-orient our awareness so we can "think about" unpredictably self-organizing, intentionally world-animating network behaviors more realistically. That is the purpose of practicing Scientific Mythology. But to do that effectively, it must fundamentally alter our experience of reality. It must transform the ordinary network configuration of our consciousness--through an actual, though imaginal, experience of "seeing networks" acting autonomously to create and order the world. The transformation of consciousness through science and symbolism

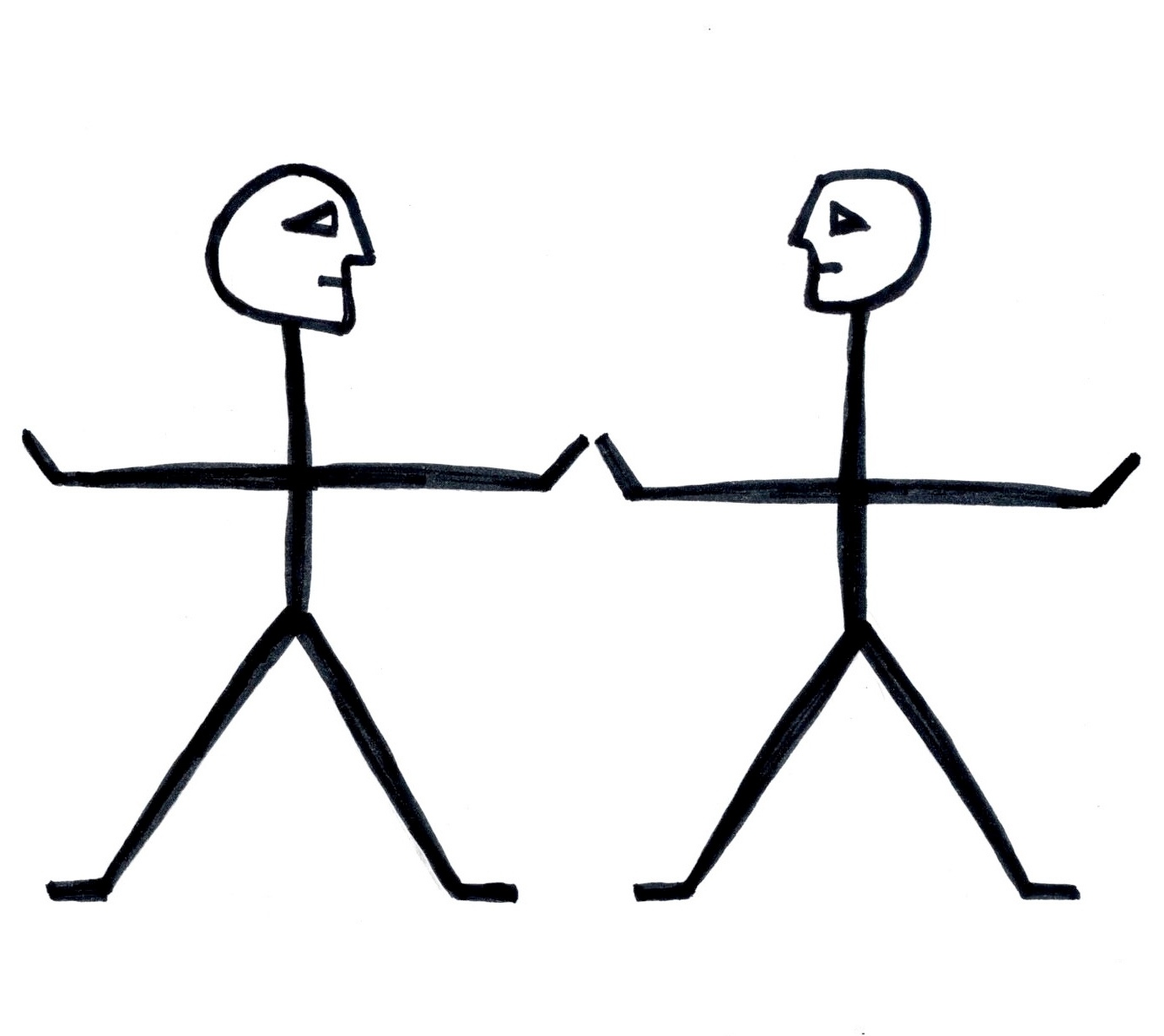

Changing the way we think changes our experience of reality: From mechanical mind through network analysis & symbolic modeling to networked vision       But how is such a transformation possible for a modern mind? How does the obviously imaginal become the actually real? Though this experience was once a primary effect of mythic culture, for us it can seem foolish delusion. That is where the science comes into the "play" of imagining the paradoxical interplay of complexity. If we, as modern minds, trust the empiricism of scientific method, we now are compelled to regard symbolic modeling of its insights with a new respect. We now have the evidence which logically compels us to engage metaphors of metamorphosis as mirrors of reality. The Practical and Cultural Motives for Scientific Mythology

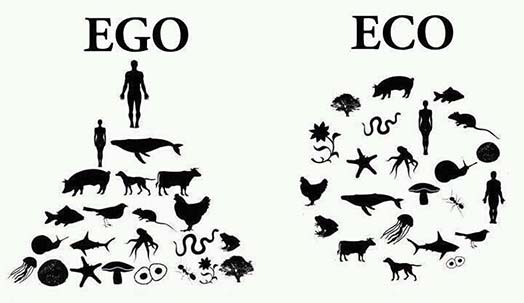

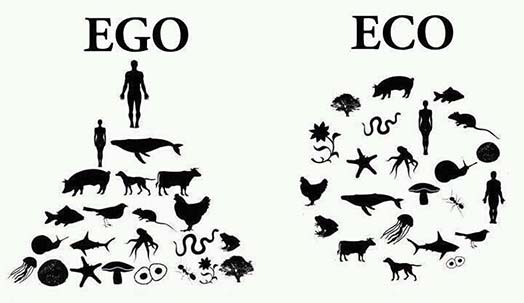

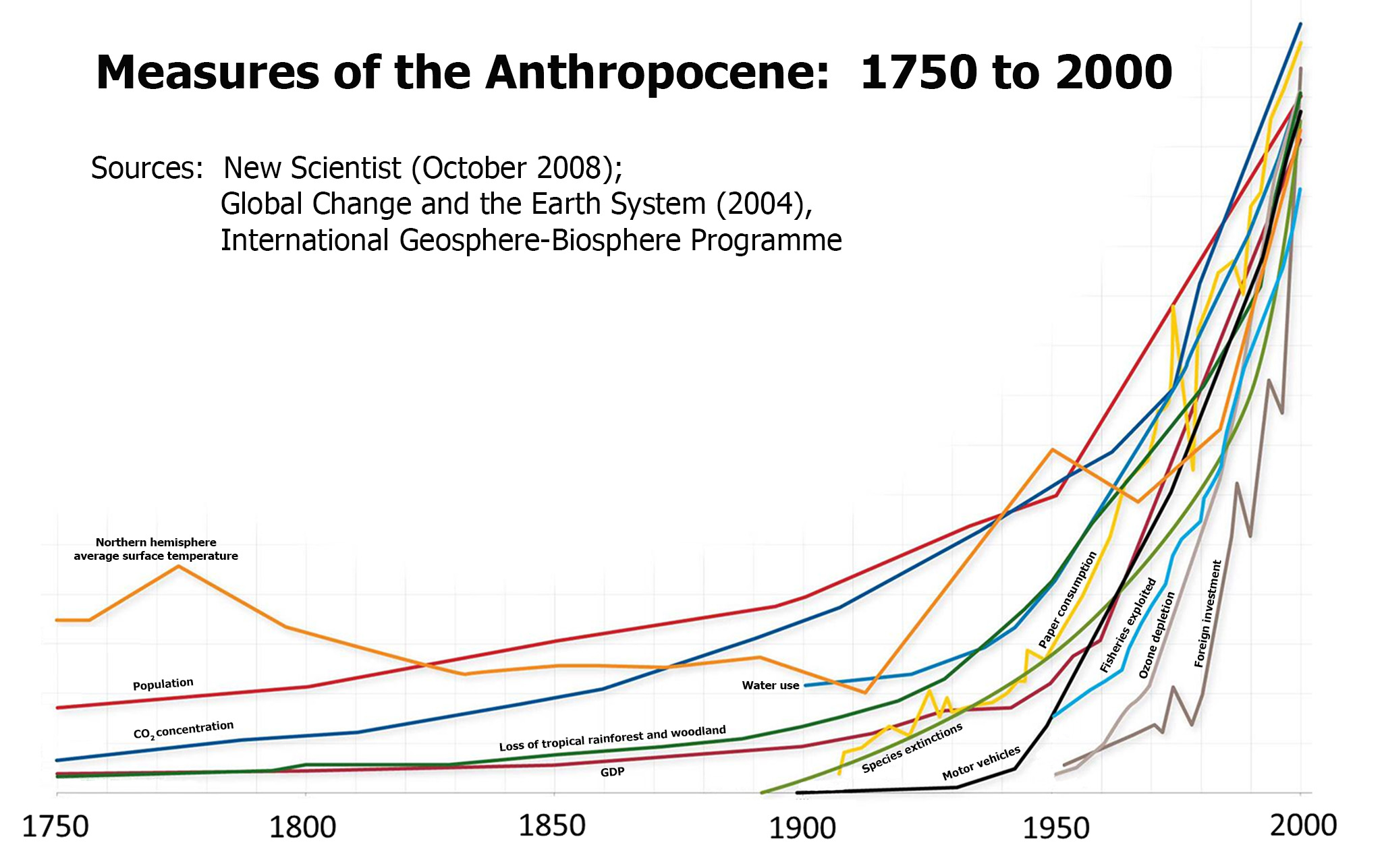

Practically speaking, gaining more awareness of complex systems and their autonomous networks provides a vastly more realistic perspective on how we and the world actually operate. It enhances our ability to interact with the willfulness of networks that we cannot control but can influence. However, there is also a cultural motive for making this effort. Honestly engaging the world-animating roles of networks is a radical act. It shifts our cultural worldview, from one that regards Nature as physical machinery we can manipulate, to one that experiences the world as a realm of interdependent, subjective entities which we cannot control. That makes scientific mythology a de facto spiritual practice. What the science reveals and mythic imagination symbolizes is a reality largely ordered by autonomous networks--whose mode of order creation constitutes spiritual animation. This knowledge and its symbolic experience generate the basis for a profound cultural change--a change that we must make if we are to avoid destroying the ecological systems on which our species depends. The Purposes * To appreciate the reality and effects of emergent order creation from synergistic interdependency * To perceive things and events as expressions of autonomously animating systems and networks * To understand how network character reveals hidden intentions, purposes, and functions * To experience self and world in a more pragmatically realistic and emotionally meaningful way The cultural shift from hierarchical to network mentality

The world perceived through control-obsessed versus participatory identity:  The Essential Questions

The essence of this work is to learn to ask some primary questions

about what networks exist in our selves and our society--and how they

operate with their own, typically hidden, intentions. The overall

question is, "How do network behaviors influence us and how do our

behaviors influence networks?" To discern answers to this question we

must ask the following:

* What are the actual configurations of the systems we are and inhabit? * How do their networks reinforce or retard their operations in response to different conditions and stimuli? * When networks act in certain ways, what purposes are they actually promoting? * How does a network's behavior reflect its evolution over time and how does that history influence it? * What archeytpal character is active in these network behaviors as they animate our personal and collective systems--what type of "spirits" are manifesting in their behaviors? Exploring these questions provides insight about how networks evolve over time so that their present behavior reflects its past. It also shows how our behaviors interact with networks to generate their intentionality, of which we are not aware, but which we can influence by consciously acting differently. Where to Start: Confronting Our Delusions about How the World Works The first step in applying scientific mythology is to confront our dynamical ignorance. Our knowledge of physical science has led us to believe we can explain, even control, all phenomena. But the evidence of scientific method itself now reveals this is a delusion. Neither human nor natural systems operate as we expect them to do. Our lives and societies are shaped by unpredictable transformations and intentional forces we have not been taught to perceive. By applying the network analysis and symbolic elaborations of a scientific mythology, we can identify and engage aspects of realty we currently have no method of conceiving. But that effort begins with the realization that our reflexively linear, mechanistic thinking is incapable of appreciating complexity's nonlinear dynamics. Admitting what we do not know how to think--1, 3, 5, . . .

The disproportional, unpredictably deterministic, synergistically interdependent ordering of complexity:     This shift in our sense of how and what we can know is unexpectedly difficult. It is not about definitively "knowing more" than we now know--or having more direct control of events. It is about becoming more aware of what we cannot fully know or control. It confronts us with the fundamental mystery of emergent ordering and its willful networks. This is a mystery we are, inhabit, and must have a relationship with, if we are to engage reality in any adequate manner. We cannot comprehend how our systems actually work if we view them as distinct parts that act upon each other in simple progressive actions. We must view them as interconnected wholes. If this shift to network perception is effective, one's sense of self and world will be transformed. However, our reflexive reliance upon mechanistic perspective requires us to undergo this transformation repeatedly, frequently, even interminably. It is human to seek control of events. Thus it is human to continually struggle to perceive aspects of our selves and the world that are autonomously beyond control. Our mythic imagination evolved to serve this very purpose. Mythologizing the Science -- In General and in Particulars Most any topic, context, event, or process can be explored and plotted as the constellation of an interdependent complex network, then engaged mytho-logically through archetypal, psychological, and symbolical elaborations. This can be done in more or less formal ways, briefly or in great detail. It can be helpful to begin by considering the general archetypal traits of a type of system and its network, then proceed to consider the particular way it is manifested in a given instance. Various types of networks (from love affairs to economic, educational, and political systems) express an overall range of archetypal traits, some of which are more emphasized in one particular manifestation than another. Networks involving very similar archetypal traits can manifest quite different network behavior, depending on the patterns of feedback relationships that become activated within them. Thus, if examining a particular historical event, one begins with consideration of History as a topic with an archetypal range of network relationships and dynamics, then examines how these operate in the network of a particular event. When investigating emergent transformations and network autonomy in a system of justice, one begins with a consideration of the archetypal range of how Justice is conceived and systematized. Similarly, if exploring a particular marriage, first plotting and elaborating general traits of Marriage as an archetypal system with types of autonomous network behaviors leads into identifying the dynamics of a specific marriage network. However, the process can be engaged in an opposite direction. One can begin with stories, images, or motifs from mythic traditions, popular culture, literature, and art, then proceed to interpret these in archetypal, psychological, and finally scientific terms. The conclusion in this approach is a network plotting of the interdependent relationships represented in the symbolism, followed by reconsideration of practical attitudes and actions in the real world. This "symbolism first" approach emphasizes the intuitive perception of emergent phenomena through aesthetic experience. It is particularly effective in accessing the accumulated cultural wisdom about complexity that has emerged in the symbolic forms of myth and art. Approaching these expressions initially through an intuitive engagement gives the following abstract analytical exploration a different quality. Here the science confirms our intrinsic intuition, emphasizing a sense of revelation about what we "know but don't know we know." From Science to Symbolism in Myth, Art, Literature, and Popular Culture 1. A subject is analyzed and plotted to reveal its manifestation of an operational network. 2. The plotting of that network is then explored for its archetypal and psychological traits 3. These are next explored through symbolic elaboration, in reference to stories, images, motifs, etc. 4. Everyday practical behaviors and attitudes are reconsidered in relation to the above From Symbolism in Myth, Art, Literature, and Popular Culture to Science 1. Stories, images, cultural motifs, etc, are explored as symbolic representations 2. Traits of the subject are interpreted in archetypal and psychological terms 3. These are used to constellate the symbolic relationships as interdependent networks 4. Everyday practical behaviors and attitudes are reconsidered in relation to the above The overall value of this practice is to awaken us to the hidden realities of emergent order creation and its autonomously animating networks. If we can learn to practice this perspective regularly, as a counterpoint to our habitually pragmatic states of mind, we can become much more realistic about how to act in relation to "invisible" forces that we cannot control, yet are, in fact, the primary shapers of our existence.

Contents Below with Links: >The Full Practice: From Network Analysis to Archetypal Symbolism and New Practical Strategies

> How to do It: The Stages of Network Analysis and Symbolic Elaboration > Network Analysis: Plotting Network Configuration and Operations > Elaborating Network Qualities Archetypally > Elaborating Archetypal Traits Psychologically > Symbolizing Archetypal and Psychological Network Traits > The Incorporation of Insights > The Challenge of Evaluating Network Autonomy in Human Networks > Discerning the Subordination of Mythic Symbolism to Control Oriented Social Purposes > How some Topics appear from the Perspective of Scientific Mythology > Evaluating Network Relations between Human and Non-Human Systems > Scientific Mythology as Apocalyptic Revelation  Elaborating Networks -- As as general phenomena, as collective interactions, and as specific individuals

Any

context of interactive

elements can be explored through these inquiries. Subjects from

language to love, economics, society, history, education, and politics

can be examined, both as general types of networks and in terms of how

each takes on particular form in a given historical context. In this

way, we can gain a sense of the types of network autonomy, or spiritual

animation, that tend to be expressed in various areas of thought or

activity. Again, these range from very general categories, such as how

economic, social, and political systems operate, to the specifics of

network behaviors in particular historical contexts.

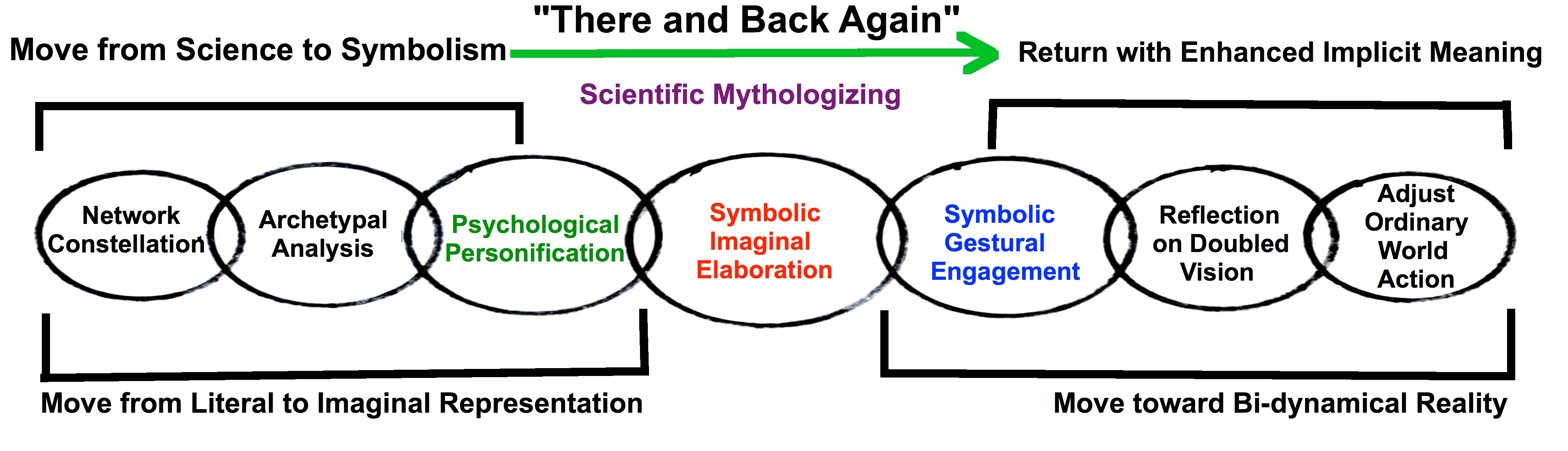

How to do It: Engaging the Stages of Network Analysis and Symbolic ElaborationA particularly important aspect of this method is its ability to reveal the archetypal diversity of emergent impetus in the collectively generated networks of human systems, from those of marriages and families to institutions and social movements. Among the most profound aspects of network analysis is how it reveals the diversity of character and behavior that can autonomously form in very similar networks--and how our ordinary perspective is blind to their willful impetus: appearances are most always deceiving! The basic aspects of Scientific Mythology involve network analysis thorough plotting, bi-dynamical differentiation, and qualitative description, followed by symbolic elaboration, then the formation of new strategies gained from these efforts. These elements have three phases: network analysis, network symbolization, and strategic reorientation. Together they constitute a six stage process. This format provides the fullest experience of identifying and engaging complex network dynamics in specific contexts. The initial analysis can be done in a general or a more technical manner. The main purpose is to orient one's awareness to the actual complex dynamics of the subject. A primary effect is to experience the ultimately unpredictable yet characteristic creativity and behavior of the system and its network operations. However, the elements can also be arranged to commence the effort with a particular story, image, or motif from myth, art, literature, popular culture, or personal experience. The subject is then explored for its archetypal and psychological traits. These then provide a basis for plotting the elements and relationships identified as a complex network. This sequence concludes with the incorporation of the experience into everyday practical strategies for engaging the network autonomies that have been revealed. The Stages and Phases from Science to Symbolism

Network Analysis: Setting the stage for symbolic elaboration 1, Constellating: How is a system's network composed, configured, and operating?

System parts and network structure are plotted as

constellated relationships to reveal interdependent dynamics, emergent transformations, and responses to changing

conditions that indicate autonomy.

2. Archetypalizing: What are the qualities of the network components, their relationships, its actions?

System

parts, network

dynamics, their variable behaviors, and the effects of network

operations are explored through compartive descriptions that suggest

their archeytpal traits and character.

3. Psychologizing: What are the motives and states of mind suggested by network qualities? The archetypal traits of network behaviors and

the dynamical attractors influencing them, are interpreted in terms of psychological character to elicit their confilcts, autonomous motives, and

intentions.

Network Symbolization: Metaphoric modeling of network dynamics, character, and animating actions

4. Mythologizing: What mythical symbols and motifs represent network traits and mentality? Archetypal trats of network structure, behaviors, and psychology are associated with metaphoric images, characters, stories,

and motifs from mythology, literature, art, popular culture, and

personal imaginations.

5. Ritualizing: How can the network be made tangible and engaged through symbolic gestures?

Network character and autonomy are imaginally embodied then engaged through symbolic contexts, and actions.

Strategic Reorientation: Living with and in the symbolized analysis of network autonomy

6. Incorporation: How does reflection on the proceeding stages guide our practical actions?

The insights and

experiences arising from preceding stages are considered for suggestions about how to interact

with the network's dynamics and autonomy in real world contexts.

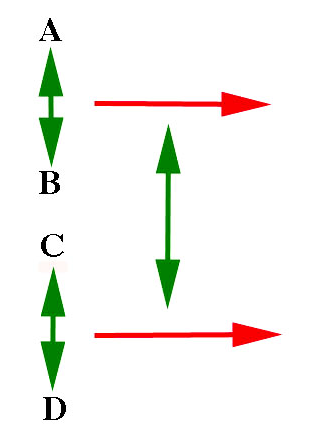

This process of network identification, engagement, and practical reflection has the "there and back again" quality of mythic ritualizing. It takes our awareness from the ordinary state of mechanical consciousness to an imaginal one in which we experience network autonomy as spiritual animator, then back to ordinary reality. This can be represented as a diagram:  The more technical part of Scientific Mythology involves an abstract analysis of how a system is composed. That allows for investigating and how its components are networked together in interdependent relationships. Given the complex dynamics involved, this analysis cannot possibly be a complete, definitive description. Its value is in making us more aware of where emergent order creation is likely arising and in response to what stimuli. It assists in thinking in the ways that networks act, reveals why they cannot be controlled, yet also indicates how their autonomy might be influenced through interacting with it. Network Analysis: Plotting Network Configuration and Operations The quest toward understanding how complex systems generate most of the order around us begins with mapping their configurations. That means identifying their parts and the relationships between these that form the basis of their operational networks. This is done by plotting them as constellations of parts and connections between parts, or nodes, links, hubs, interactions, and flows of feedback. That allows for an investigation of how the parts influence each other in simultaneous, interdependent ways. That provides a basis for investigating feed back loops that either reinforce or suppress certain operations of the system. In this way a portrait of how the system's network self-organizes is created. That portrait aids in understanding how its network autonomously self-animates it. Plotting the Logic of Emergence

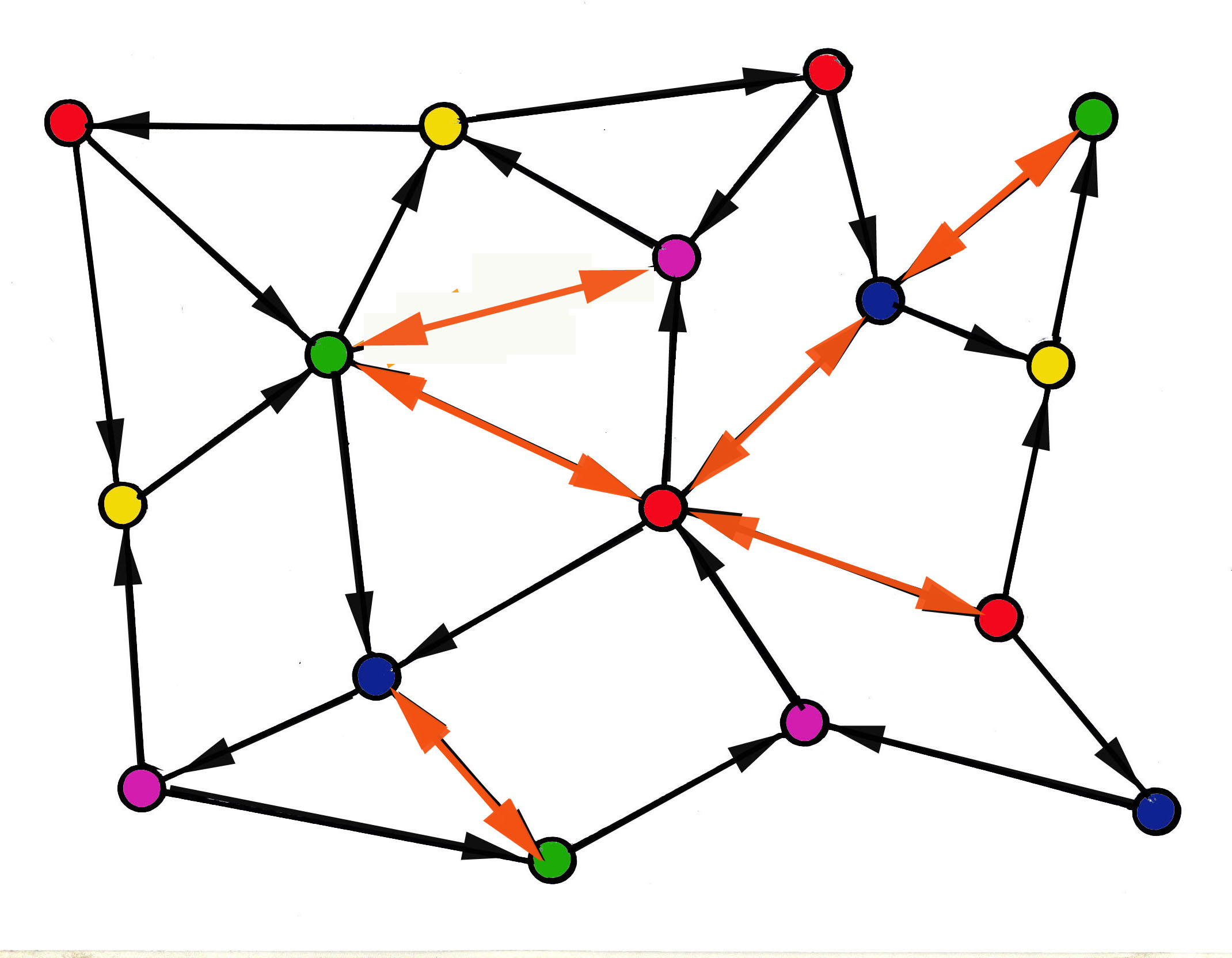

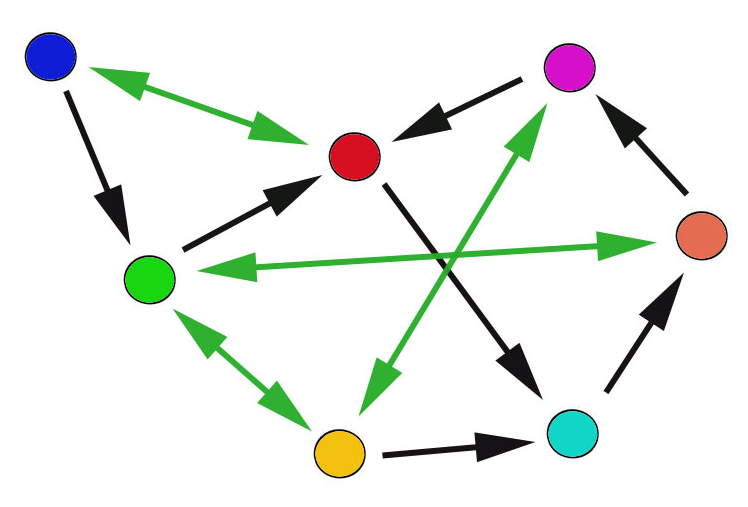

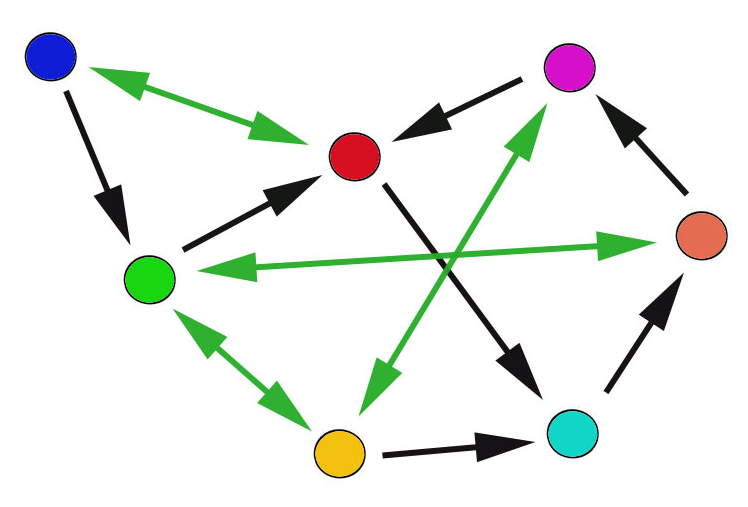

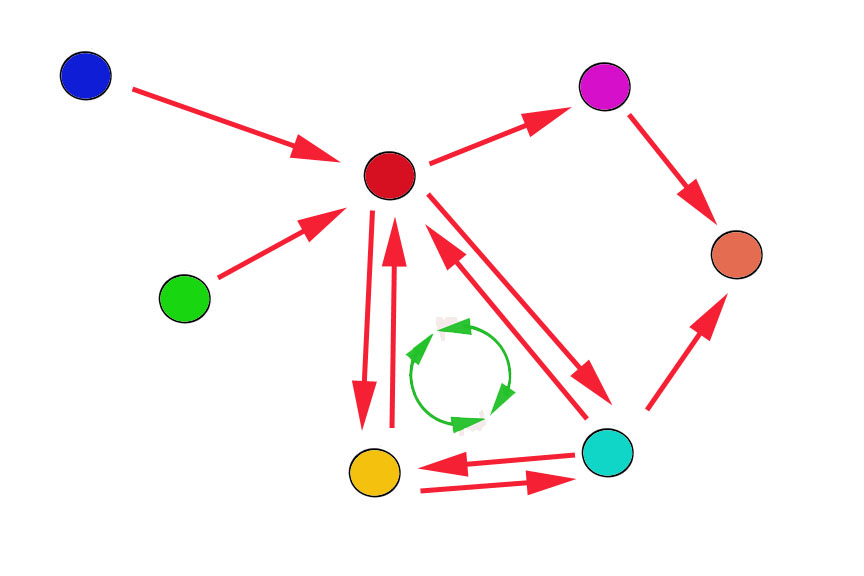

Network constellation reveals interactions whose interdependencies synergistically give rise to network autonomy:

This basic concept of network interactivity and its emergent self-animating autonomy guide us in plotting the parts of most any complex event or subject as a system network. First the parts and their links must be constellated. This visualization immediately alters our familiar perspective on a subject or phenomena. Then the ways those parts interace with each other, under particular circumstances, in specific contexts, must be examined to reveal varying formations of feedback loops among them. That begins the process of revealing the sources of a particular network's autonomy and its characteristic mode of self-animation--its network soul. There is no exact or perfect way to do this. But making the effort always reveals unexpected, paradoxical relationships, and emergent effects on how a network is creating its systems behavior. This network analysis first shifts our persepective from expectations of hierarchical control and sequential, mechanistic causation, to awareness of constellated interdependency. Moving from hierarchical to constellated perspective

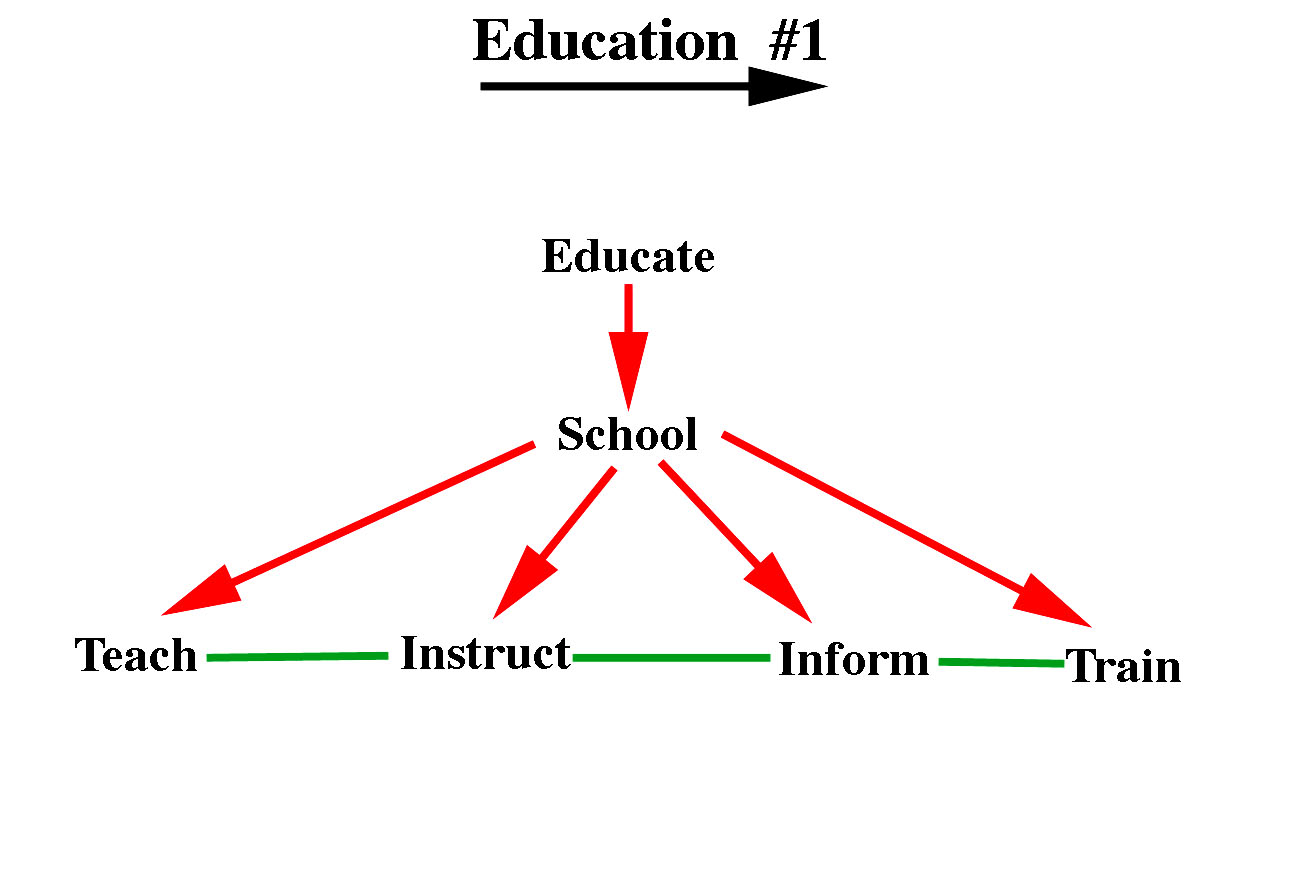

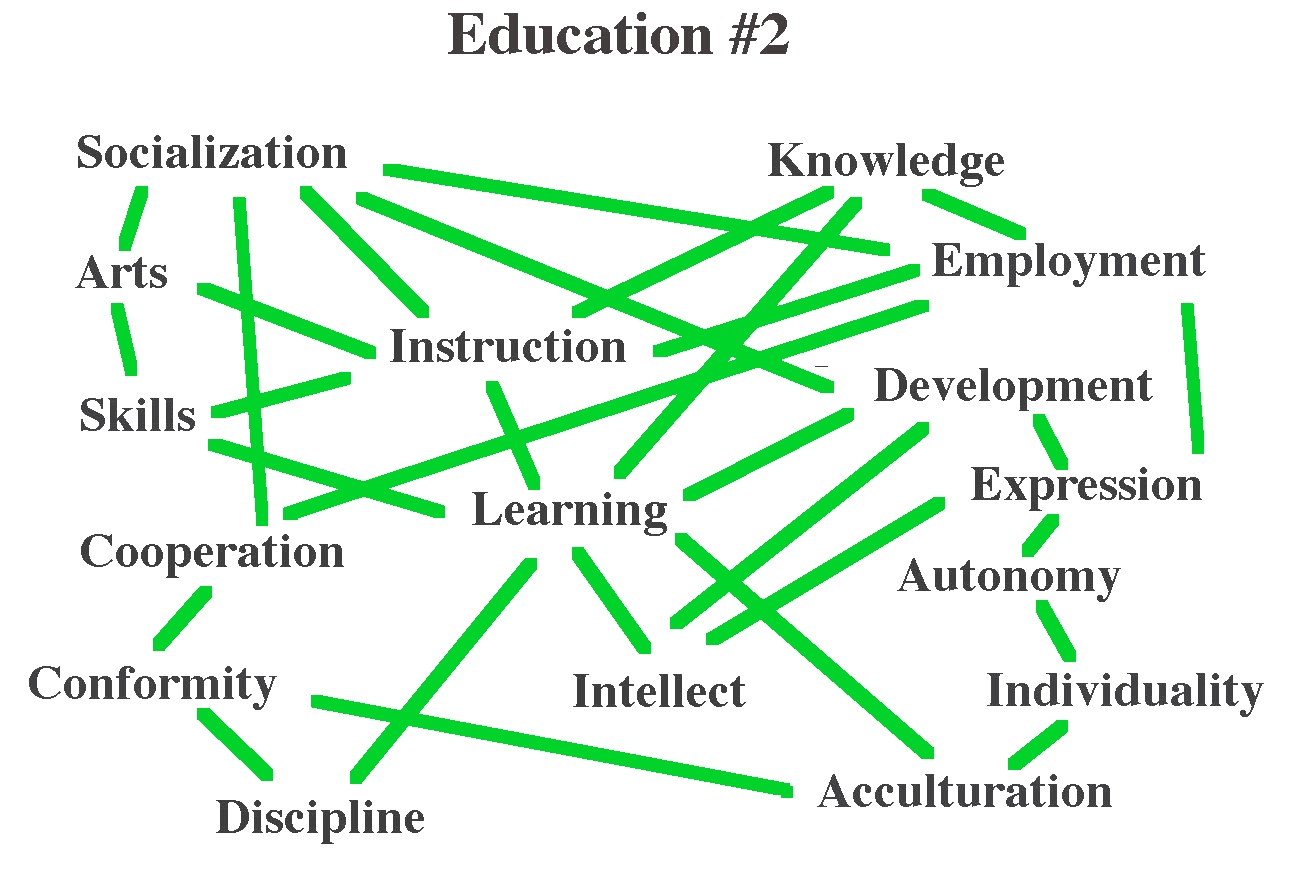

Education as a composite sequence versus as a complex, variably interactive network:   Identifying the Nonlinear dynamics of Self-Organizing Factors in Feedback Loops Once the general plot of a type of system is constellated, the specific behaviors of a particular manifestation of it can be more thoroughly explored for its behavior animating feedback loops. These are circuits of interaction among system parts that generate amplifying or dampening effects on aspects of overall network behavior. Self-organizing systems generate the relative consistency of their operations, the self-similarity over time that gives them recognizable identity, through the on-going emergence of these interdependent interactions. Thus one looks for nexes of interactive feedback which give an indication of where self-organization might be concentrated. Plotting the general topic assists in locating regulating feedback loops in a given manifestation of it :

Plotting these enhanced areas of interactivity assists in understanding

what parts of a system are acting together in ways that modify their

effects and give overall network behavior a particular impetus. It can

be relatively easy to identify specific, one-way actions of separate

parts upon other parts but more difficult to identify how these actions

interact in synergistic ways to produce effects not associated with the

separate parts and their properties or even intentions. The dynamical

complexity of emergent ordering becomes more evident by distinguishing

how relatively linearly dependent actions become intertwined in ways

that generate more nonlinearly interdependent effects. This is the

by-dynamical differentiation of network analysis.

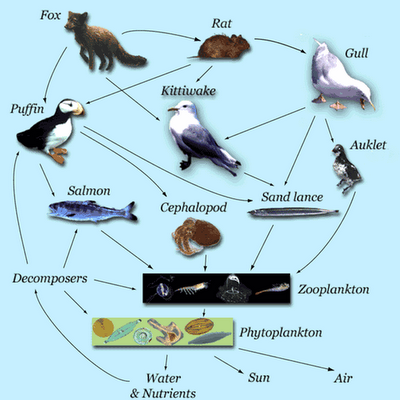

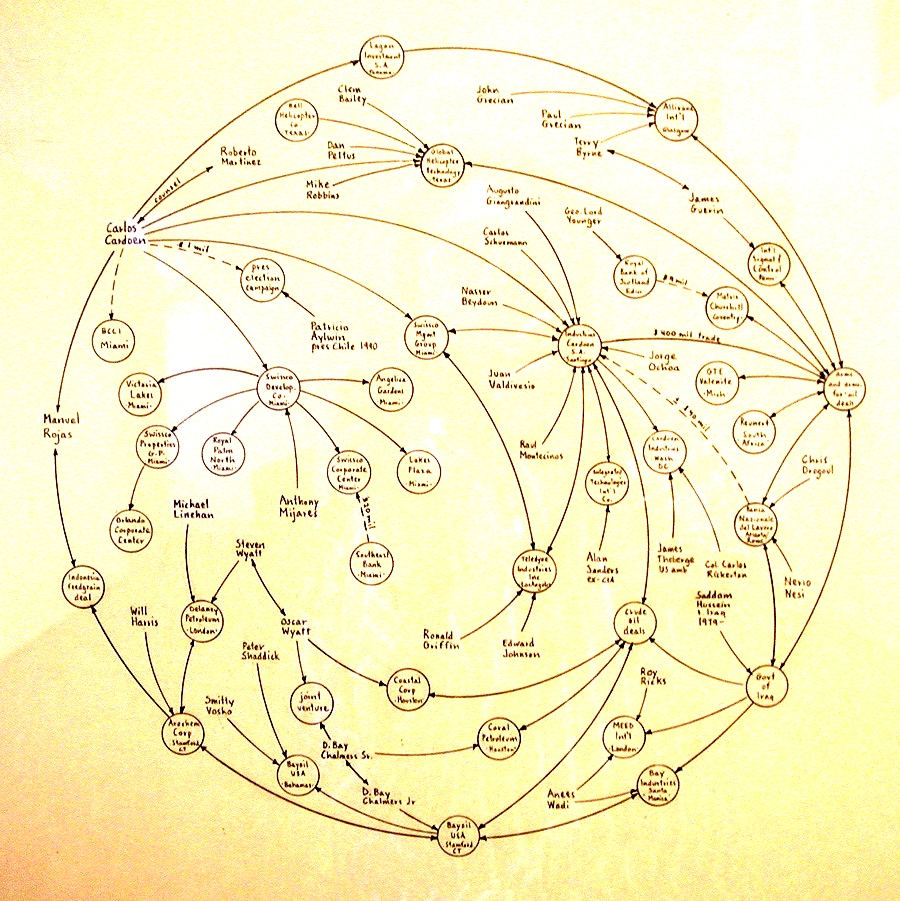

Animals in an ecology and humans in social groups often act mechanically to manipulate things and events. But these physical acts can interact to generate emergent ordering and different intentionality in a larger meta-system network. It is this synergistic effect that associates with concentrated areas of interactive feedback. However, part of the mystery of networks is that what appears to be a minor part of a system can contribute influence that triggers a profound shift in network operations. Thus one must be alert to any indications that peripheral aspects of a network might actually be playing a primary role in how it determines its operations. Many actions make for transformative interactions

Ecological food

web: Mark

Lombardi's graph of "players" in the Iran Contra Scandal

We tend to think in terms of hierarchies and "major players" when regarding systems--from lions to CEOs. But the science tells us that these are more expressions of the interdependency of the overall network and have much less control than appearances indicate. Networks self-organize in multi-directional flows of feedback, being transmitted in every direction concurrently. Thus their operations and intentionality derive more in a "bottom up and side to side" manner. That is part of why seemingly minor aspects of a system can have meta-scale effects. Thus "visualising networks" requires a defuse perspective that can track multiple trajectories and intersections of influence to notice how these "come together" as emergent effects in network behaviors. Tracking the Emergence of Nonlinear Transformations of Network Operations Identifying both nexes of mutually modifying feedback loops and the potential influences that peripheral-seeming system elements and actions might be contributing to these aids in noting where and when a network undergoes a nonlinear or metamorphic transformation. These are appear as shifts from more predictable continuity to a new, unpredictable status and properties. In terms of dynanmical attractors, a system is emergently "jumping" from one attractor pattern to another through an increase in nonlinear dynamics. When such changes are noted in network operations and their effects, close scrutiny might give indications about what interactions have shifted and thus how the transformation gets triggered, if not exactly how it happens. Nonlinear transformations to a new network behavior pattern

Sudden arguments are emergent leaps to new dynamical attractor states:   Seeking Simple Rules that produce Complex Behavior A fundamental insight of complex systems and network science is the role played by very simple actions or "rules" of interaction. The flocking of birds, termed "murmuring," is the manifestation of a nonlinear, metamorphic transition to a complex meta-network, which expresses the emergent purposeful intention of evading of predators. However, it is thought to arise from the simple "rule" that each bird follows the actions of a few neighbors. Similarly, simple social conventions in human groups, such as ways of greeting and language usage, can have unexpected effects on the behavior of the overall meta-network that emerges from seemingly superficial interactions. Such minor aspects of network operation can "add up" to emergently compose potent influences upon an overall system. Many of our daily habits seem insignificant, but close analysis can reveal how they interact to generate transformative feedback loops that either amplify or suppress aspects of larger network behaviors. Simple rules can have complex effects

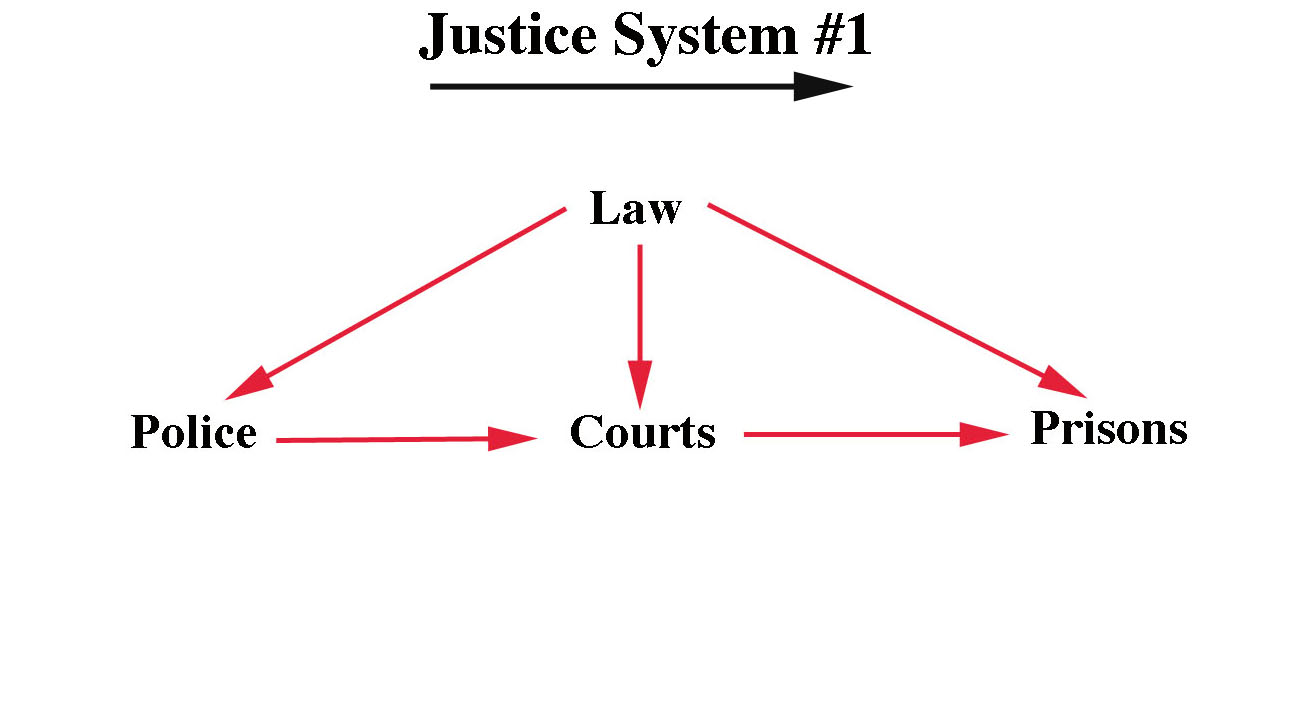

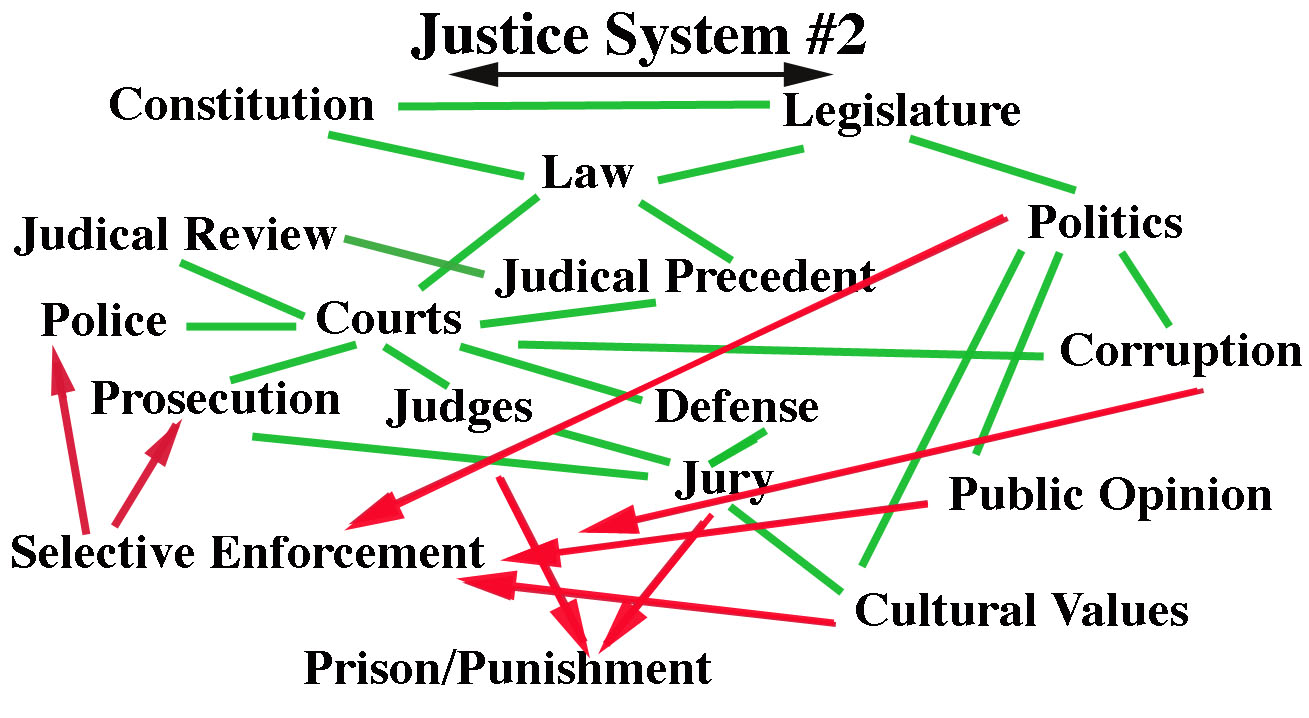

Fish shoaling and human social grouping arises collectively yet unpredictably from individual acts:   Recognizing Autonomous Network Responsiveness However, changes in external influences, or inputs from other networks, can alter how feedback loops govern overall network behaviors. The same system configuration can manifest variable network operations depending on how sub-systems of the larger system respond to shifting factors. From systems of interpersonal friendships to those of commerce, politics, and religion, network behaviors are not only vastly more complex than we assume but variably responsive to changing inputs. To understand the character of their network autonomy, one must consider typical and atypical variations in its behavior. That means identifying how feedback loops emerge in relation to various conditions and inputs from other systems. Networks do not "stand alone," they are interdependent with other networks and reciprocal participants in meta-networks. Our habitual view of natural systems is that these are mechanisms. The behavior of human systems tends to be understood as driven by the deliberate choices of individuals. However, network analysis reveals that these systems act in their own right. Their networks process information and generate impetus which does not come specifically from individual persons--just as ecological and economic systems do. That is why they are termed autonomous: they actually perceive and respond to changing factors as "actors" in the overall interplay of humans and their systems. A recognizable network, such as a justice system, appears to have a predictively repetitive structure and set of procedures. But it can act quite differently in response to even minor changes of input. By our shifting perception of such a system, from a hierarchical view of how it is designed and assumed to operate, toward a more realistic complex of interacting factors, various potential feedback loops become evident. In this view, the actual components and networked relationship of a "system of justice" are revealed to involve factors that are not supposed to be involved in it. The ideal and real system of justice

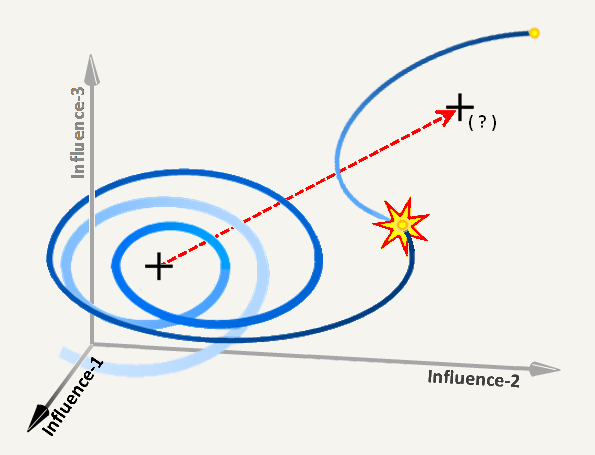

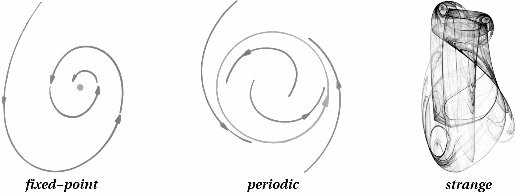

Plotting a more actual constellation of factors and their potential feedback loops:   Referring to the constellation of factors interacting in the networked operations of a justice system shown above, it becomes evident that much more is "at play" than might be expected. Many potential conflicts of interest become evident among subsystems that can be networked together in various ways depending upon inputs that trigger flows of interdependent interactions. These pose quite different areas of potential feedback loop formation that amplify some aspects of behavior why suppressing others. Impetus that promotes a significant shift in the network behavior of a Justice system might be coming from a a particular defendant or judge, or more peripherally from public opinion, political ideology, or corruption. However, the crucial point to understand from the science is that autonomous network behaviors arise not from simple sequences of actions, but from mutually modifying interactions. Thus we have to look for multiple factors that modify each other, as the likely feedback loops where network intentionality is synergistically emerging. Visualizing Network Behaviors as Variably Synergistic Dynamical Attractor Landscapes Appreciating the variably synergistic--and ultimately uncontrollable--dynamics of these self-organizing relationships is aided by thinking in terms of dynamical attractors. Some dynamical aspects of these systems are relatively regular and predictable, others are profoundly unpredictable and "strange." The multiple, shifting patterns of strange attractor graphs provide a way to image the variable responses of systems to changing inputs and tasks performed by network animation. Attractor images of predictably consistent and unpredictably autonomous behaviors:

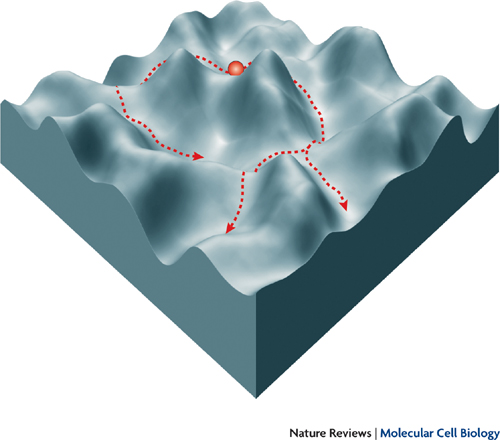

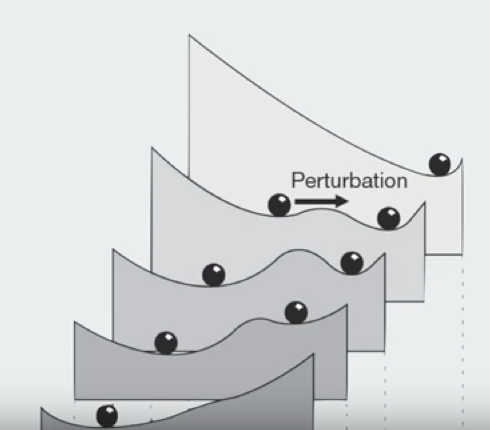

This reference to the science of dynamical phenomena provides the further model of system components as dynamical attractor landscapes, within which their network behavior is constantly emerging through responses to variable factors and inputs. Depending on the degree of perturbation from inputs and the activations of system memory, the relative impetus of differing dynamical attractors can change, resulting in shifts in network behaviors from one relatively steady state to another. A system's attractor landscape can shift in response to in inputs

Linkd to video animation of changing attractor landscapeVarying factors can alter dynamical relations among system parts, changing network behaviors:   To bring these abstractions back to real world contexts, we can think in terms of how differently one behaves in the company of a particular friend or family member as opposed to interacting with some other one. Interacting with different people activates different dynamical attractors in one's own system, prompting distinguishable shifts in one's own network behavior. Similarly, individuals often behave in response to one set of values when working for a corporation but another when dealing with people outside of the dynamical attractor field of that system context. These are sort of the details to notice when plotting and evaluating the variable behaviors and relevant factors associated with a network's overall operations, Tracking Network Behavior in Relation to System History as the Evolution of Active Memory Understanding network behaviors and the feedback loops these manifest at different times, in response to various inputs, inevitably involves references to their system's history. Complex systems evolve over time as they adapt to changing factors within and outside of them. Their networks operate in reference to their system's past formations and actions which give them impetus. Thus their past influences the responsiveness of their current network autonomy. Whether a system is an ecology or a marriage, the past plays a part in how a network self-organizes or adapts its system on an on-going basis. When seeking to identify what factors or inputs trigger activation of particular feedback loops in a network, thus particular patterns of network behavior, it is useful to consider its history. Thus a network analysis of a justice system requires examining how it has responded to various historical events or conditions. Legal systems formalize memory in terms of interpretations of laws recorded as legal precedents. The operational network of the system can, at any given time, choose to affirm or overturn the directives of these historical events. But system memory also involves social, cultural, and economic events that are not overtly recorded data. A legal system that appears to be configured in ways that will adjudicate all cases according to the same principles will often respond to similar cases differently, depending on how system memory is activated by various inputs. Courts considering the guilt or innocence of wealthy individuals tend to reach different conclusions than when judging impoverished ones even when charged with the same offenses. Such a tendency need not arise from the attitudes or beliefs of the judges, lawyers, and jurors involved in a case. It can be understood as an impetus in the system's network conditioned by historical patterns of behavior that triggers a particular feedback loop in its emergent behavior. Network autonomy is not controlled by the overt structure of a system at a given moment. Networks can abruptly reconfigure system operations moment to moment. Thus understanding network behavior requires close examination of how historical factors come into play in the interplay of a system's operation relevant to specific conditions and inputs. Similarly, such systems operate with the purpose of sustaining their own operations. Thus their networks often act autonomously to preserve or adapt their systems in reference to future possibilities. So the considerations of the future influence network behaviors as well as does it "memory" of the past. That makes effective network analysis a matter of comparative modeling over time. One must attempt to observe how network behaviors are influenced by past and potential future consequences of their autonomous agency. Consequently, the most apt plotting of a system and its network visualizes a kind of animation of it actions over time and in relation to varying inputs. Comprehending Network Change: Irregular System Continuity versus Metamorphosis and Collapse Tracking variability in network behaviors enables us to perceive how their relative continuities, their self-similarity over time, actually emerge from irregularities. The self-organization of complexity cannot arise from progressive consistency. Ecological science uses the term "disturbance regime" to describe how perturbations such as floods, lighting strikes, fires, and droughts actually promote the robust operations of an environmental system's meta-network. The adaptive self-organization of that network emerges in part from being thusly perturbed. What appear to be relatively regular behaviors over time are the result of interdependencies among system parts that are enabled from unpredictable yet essential disruptions. Thus what appear to be system-threatening events, or even conflicts between sub-systems, such as animal species, are often a crucial basis for emergent network self-organization. Noting how patterns of feedback within a network respond to disruptions gives some idea of how the autonomous self-regulation of a network functions. However, even robustly adaptive networks can be disabled by some types of disruption. Network analysis can show us how even seemingly minor perturbations can, over time, trigger sudden reconfigurations of network operations or even the system itself. The decline of a single species that functions as a crucial part of feedback through an ecological system might not produce overt effects for years into the future. Then suddenly the system's network can make a relatively abrupt shift, either toward a new pattern of behavior or toward collapse because it can no longer self-regulate. Thus networks can respond to disruptions by transformative metamorphosis, in which they become notably different systems and networks, or become dynamically chaotic and disintegrate. However, beyond collapse, chaotic dynamics can give rise to sufficient interdependencies that enable new forms of self-organization, and the emergence of a new system and network. Sudden transfomation or collapse are referred to in the science as "tipping points," meaning moments in time when changes within a system or in its external environment suddenly "add up," creating pressures that the system's network can no longer accommodate. The preceding patterns of network behavior can no longer emerge because the interdependencies that produced it cannot be sustained. This time delay in the response of a system's network to sustained disruption actually testifies to the resilience of emergent self-organization. But it makes predicting network responses to perturbation extremely difficult. This issue is essential to keep in mind when analyzing network behaviors and attempting to understand how these can be influenced. Both extreme and minor perturbations can have a variety of consequences, from enhanced network robustness to eventual chaotic collapse. The plotting of how feedback functions in network relationships, particularly with external factors, can give some idea of what changes might have more profound influence upon overall network behavior and sustainability. That provides us with a sense of how to try to influence network change without dissabling its adaptive potential. Elaborating Network Qualities Archetypally Exploration of how a system's components are network into relationships with each other, and with external factors, allows us to describe its qualities by asking what it is like. Relying particularly on adverbs and adjectives, traits of the emergent ordering which gives a phenomenon or network its shape and behavior are explored. What are the qualities of his configuration and actions, the way it operates under certain conditions, its conflicts? This constitutes an archetypal analysis of network dynamics and behavior. These descriptions are not literalistic definitions because they seek to enhance our awareness of something that is not accessible to such representation. The emergent aspects of things, events, and systems are intrinsically obscure. So the method of archetypal analysis is comparative, relational, resonant. Here our exploration is already approaching the imaginal method of myth and art. The accuracy of this effort arises from "staying with" the evidence of the subject and the plotting of relationships among its aspects. A basic aspect of archetypal differentiation is distinguishing more linearly dependent actions from more nonlinearly interdependent ones in the preceding network analysis assists in qualitatively describing the ways network operations are generating emergent ordering. Relying on adjectives and adverbs to describe system and network traits begins the process of psychologizing and symbolizing it as an intentional entity in and of itself. Elaborating Archetypal Traits Psychologically Interpreting network autonomy in psychological terms is an extension of archetypal elaboration. The intent is to characterize the qualities of a networks' behaviors in regard to its subjective responsiveness to various factors and the temperament of its intentionality. This can be done in casual language as well as more formal psychological terminology. Thus a particular example of a political system, such as a political party, might be characterized in as aggressive, emotionally unstable, paranoid, or even sociopathic. Psychological profiling of networks often reveals paradoxical or conflicted character traits that are expressed as a form of psychic dissociation. The "minding" in networks can be schizophrenic. In this regard, thinking in terms of human psyches, networks can be considered to manifest more conscious versus more un- or subconscious aspects of subjectivity and intentionality. Depending on the extent of the analysis, a network can be psychologized in a very general way, or to through a more formal psychological profiling. The main objective is to begin to perceive network behavior as an expression of subjective self-awareness and intentionality that constitute a personality influenced by its history and its relationships with other networks. That promotes understanding it as a form of spiritual animation. Psychological elaboration is also useful for gaining insight into network intentionality. Psychological analysis of humans as mental networks reveals the diversity and inherent conflict that underlie their self-organizing cohesion. It often indicates that a the pattern of a person's behavior indicates that conflicts within their mental network are, in effect, attempting to "work them selves out," to become more interdependently integrated so that the overall network of the system becomes more coherently sustainable and adaptive. Such enhanced integration is the goal of much psychotherapy. When we view networks other than human minds in this way, we gain access to understanding of why their behaviors manifest as they do. Further, it becomes more evident how those networks might be influenced to facilitate their re-self-organization toward greater reciprocity with other networks. Psychological analysis of human mental networks "tells a story" about what is happening "in there" and sometimes why. Thus it helps prepare the way for symbolic elaboration. Symbolizing Archetypal and Psychological Network Traits The preceding three stages of network analysis, archetypal qualification, and psychological characterization provide the basis for symbolizing network dynamics. In this effort, associations are made to images, stories, and motifs found in traditional folk or fairy tales, mythologies, literature, art, and even popular culture. These associations assist in conceiving a network as a "creature" that has a "story," and a past history that is active in its present operations. An important extension of this mode of representing network autonomy is the engagement of improvisational symbolic imagination. The input of preceding stages is allowed to prompt spontaneous associations out of one's own intuitive responses. In effect, one practices the same generation of associative symbolizing that creates myths and art in general. Symbolizing network dynamics psychologically

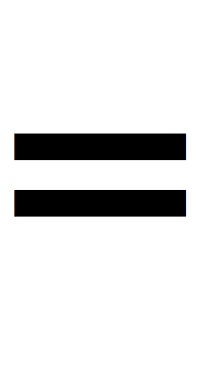

How to visualize the archetypal character of an intimate two person relationship:     When seeking to symbolize how the network behaviors of a particular interpersonal relationship generates the additional network autonomy of a third, such as in a marriage, there is a panoply of symbolic references to consider. The creator-destroyer god Shiva, in union with the beneficent Parvati, emanates the network character of the jovial spirit of good fortune, Ganesha. The story of the Bear King requires a woman to accept a great beast as her partner in order that he might metamorphose into a human companion. Apollo's obsessive pursuit of Daphne manifests her transformation into a tree. Ariadne's essential assistance in Theseus' slaying of the minotaur is rewarded by abandonment, which leads to her becoming the consort of the god Dionysus. In the tale of the Frog Prince, a haughty princess avails herself of the aid of an ugly frog to retrieve her "golden ball" that has fallen into the watery depths, with the promise of taking him to live with her, only to reject him. But she is compelled to honor her pledge, with unexpectedly transformative results. And so on the inumerable variations of such symbolic tales and motifs goes. Images and tales of relational dynamics--and how these can transform

Shiva + Parvati = Ganesh: The Bear King: Apollo and Daphne: Theseus and Ariadne:     The Frog Prince: Psyche and Eros:   Echo and Narcissus; Tiamat and Marduk: Hutter's Couple:    The stories and motifs of myth, literature, and art provide archetypal references not only for how system networks tend to manifest their character, but also the conditions under which that character is likely either resist change, be transformed, or to disintegrate entirely. There are stories that symbolize "successful" transformation and stories that represent trajectories of destruction. Considering these can assist in understanding how to interact with a network in ways that might encourage its transformation or avoid its catastrophic collapse. This symbolization of network dynamics and character can be carried a step further by engaging the symbols as the actual "spirits" at work in the networks being explored. This is effectively ritual process in which symbolic contexts, forms, and gestures are generated as a way of enhancing intuitive understanding of the networks autonomy--and how one might relate to it in ways that influence its behaviors "in the real world." This effort can be thought of as a "communion with complexity," as a way to maximize an experiential encounter with a network's intentionality, which might seem either benevolent or malevolent--or both. Though there is a significant analytical element to this process, it is not directed toward the typical purpose of logical or scientific analysis. Neither the science nor the symbolism involved can provide us with conclusive knowledge that will enable us to plan and act with certainty about outcomes. This effort is about learning how Nature acts in genuinely mysterious ways to make and maintain the world. It has the purpose of becoming wiser about the interdependencies from which we ourselves emerge, as do other aspects of the biosphere. Rather than enhancing our capacity for command and control of events, it teaches us that there are autonomous forces manifesting in all manner of system networks that, due to the very dynamical conditions of their emergence, cannot be controlled. But in the process of discovering these willful forces, we can learn about their archetypal tendencies. From this knowledge we can become more intuitively sensitive to how types of networks are likely to behave, and how they respond to various conditions. The autonomy of networks are, after all, interdependent with each other, responsive to the character of other networks around them. Thus, though they cannot be directly controlled, they can be influenced. The wisdom gained from scientifically mythologizing networks reveals that influencing them often means acting in what seem, to our ordinary pragmatic perspectives, indirect, illogical, and paradoxical ways. Network Wisdom and the Surrender of Heroic Control Learning to "play" with the interplay of network dynamics in a conscious manner not only enhances our capacity to influence them, whether by facilitating or redirecting their behaviors, it brings greater meaning into our experience of self and world. There is much more happening, with far more complex intentionality, and in marvelously more mysterious ways, than our culture has led us to believe. But we must be wary of a tendency to invent egoic fantasies about these mysteries. Entertaining fantasies, as in the entertainments of popular culture, tends to favor the control oriented role of heroic conquest and victory over evil enemies. The world according to complexity science, and the fullness of any cultural mythology, is not so simple. The heroic protagonists of ancient myths are often shown to fail in their attempts to attain control over events. They express the hubris of human mentality in its impulse toward manipulation and dominion. In so far as they do survive and succeed in their ventures into the "other world" of mysteriously animating spiritual forces, they most always do so because they are assisted by those forces. Stories classed as fairy tales particularly emphasize the necessity of having such assistance in coping with the personified agency of autonomous networks. The wisdom about interdependency it offers is ever logically paradoxical and not a matter of belief in good and evil. Gaining access to this wisdom requires a surrender of the longing for certainty, control, and righteousness. Through such a shift in our mentality, we can learn to think in terms of two dynamical modes of order creation. That make us more able to "live in both worlds," that of mechanically predictable events and that of complexity's emergence and autonomously animating networks--what myth perceives as the ordinarily profane and the extra-ordinarily sacred. In this way one is better able to embody consciousness of one's own, paradoxically conflicted yet self-organizing meta-network of networks. You Can't Get There from Here: The Indirection of Influencing Network Behaviors As the science indicates, changes in network behaviors emerge from shifts in interdependencies. Thus it is typically not possible to simply manipulate the aspect one wants to change. Attempting to eliminate violent behavior in the network behavior of a person or group by blocking it does not interact with the many interdependent origins of the violent impetus in the network. As the science indicates, changes in network behaviors emerge from shifts in interdependencies. Thus we cannot simply change one aspect by directly manipulating it. Trying to suppress violent behavior in the network of an individual person or a group is not likely to succeed because that behavior has many, interdependent origins. Getting Practical about Network Autonomy--from Reaction to Interaction Beyond gaining wisdom about the uncontrollable aspects of complexity and network autonomy, practicing Scientific Mythology prepares us to act more pragmatically. Once we comprehend that networks not only act autonomously but react unpredictably to our attempts to "force" their systems, a strategic shift becomes possible. It becomes evident that seeking direct control might gain short term advantages, but that these come at the risk of catastrophic backlash resulting from disruption of self-regulation in the networks thusly manipulated--such as ecologies . The tactics appropriate to exerting long term, perhaps even transformative influence upon networks without provoking severe disruptions can appear indirect and irrational to mechanistic mentality. Though it sounds simplistic, the difference can be stated simply as that between "reacting" and "interacting." Human behaviors based on hierarchy and control tend to foster reactions to stimuli, without regard for the complexities involved in a situation. Our initial responses to events tend to have this "fight or flight" quality. Behavior informed by awareness of complexity can be much more subtle and effective in influencing network behaviors. Consideration of the paradoxically diverse and contradictory factors necessarily exerting influence on the emergent behavior of any complex network alerts one to the limits of controlling these, while at the same time provides insights about how one might act to influence their re-self-organization. "Pushing back" or deferring to overtly obvious network behaviors both tend to reinforce existing patterns. Entering into the interplay of the factors that are generating the behavior tends to be more effective--not by exerting control, but by providing additional interactions that can facilitate a network "making a shift" of and within itself. A most accessible example of this is in intimate two person relationships. It is usually ineffective to try to force your friends and intimates to behave differently. But sometimes just responding to their actions in an unexpected, perhaps overtly symbolic manner can trigger a sudden shift in their psychic network operations. Getting practical about network autonomy can involve "behaving strangely." The Affects of Scientific Mythology

These efforts move our consciousness into a more complex perception of how forms and events actually arise--as the emergent effects of conflicted yet cooperative interdependency. Consequently, our ability to anticipate and interact with the uncontrollable autonomy of the networks we engage, in and around us, in everyday reality. The benefits are not enhanced control or prediction. Rather, they are an increase in awareness that expands understanding of complexity, thus our capacity to act in relationship with the subjectivity of complex networks--instead of acting in ignorance of them. It helps avoid suffering the often disastrous consequences of assuming we can define and manipulate anything and everyone. That awareness, and its experience of subjective network autonomy through symbolic imagination, also foster greater empathy for the "others" of natural systems--from discrete animals to entire ecologies. Such encounters with the sentience of the non-human offers a more compelling sense of the intrinsic interdependency of life itself. All of which aids in living more fully, with/in the paradoxically conflicted, neither good nor bad dynamics of reality. Despite its abstract analytical elements, the practice of Scientifid Mythology is a profoundly aesthetic one. It has the potential to bring us to sudden intuitive understanding, such as experienced through encounters with works of art. This is the affect of a metamorphic transformation in the configuration of our mental networks, which can be termed a state of mytho-logical mentality. Human Systems are Different Though complex human systems manifest emergent network autonomy through interdependency, like those of the rest Nature, human ones can be significantly different. Systems configured on hierarchical frameworks of authority and bureaucratic procedure are less reciprocally responsive to flows of feedback within their networks and between these and the networks of other systems--especially non-human ones . Though systems of social hierarchy are common to many animal species, this quality of command and control exercised by an elite sub-network over an entire meta-system can become elaborately amplified in human societies. The institutional structures of organizations associated with civilization, such as governmental, military, law enforcement, commercial, financial, and educational systems, manifest an exceptional capacity to act in insular, competitive, dominating, and exploitative ways. Thus in seeking to understand network behaviors in human systems, some special considerations are required. Our species dependence on manipulative control as our mode of adaptive survival has profound consequences. In the modern civilized sense of the word, systematic tends to convey a meaning of hierarchically ordered, mechanistic operations. That is how civilized systems tend to be conceived and configured to function. Yet despite this intention and expectation, even the most hierarchically structured human social systems actually manifest complex dynamics and network autonomy. Armies have rigid command and control regimes that give their elites the power of life and death over subordinates. But in their actual operations there arise interdependencies that exert the influences of network autonomy over the behaviors of the entire system. This paradox of complexity and network autonomy operating even in the most hierarchically structured systems is difficult to appreciate, but crucial to a realistic understanding of how our systems actually function. Emphasis upon hierarchical privilege and power does insulate elite sub-systems from being reciprocally responsive to the other aspects of an overall system that they manipulate and dominate. But this same operational trait feeds back into the less obvious complexity of the meta-system to influence the character of its network autonomy. In short, the overall network behavior in hierarchical systems tends to reiterate this hierarchic bias. Complex networks, after all, demonstrate an intrinsic, autonomous impulse to sustain and adapat their systems for future sustainability. Thus a complex system structured to have pronounced command and control functions will tend to act autonomously to enhance this quality. Natural systems evolve within constraints of reciprocal interdependency that they cannot readily evade. Predators are dependent upon their prey, which they cannot directly control. But humans have evolved capacities for manipulative control that evade this reciprocity with other systems. That ability appears to be directly linked with the mass social systems of agrarian-based civilization and its amplification of technological methods for manipulating both natural and human environments. Civilization can only exist by way of amplified command and control systems that enable the direct exploitation of subordinates by elites--whether of humans over plants and animals or over other humans. Nonetheless, human social systems remain complex adaptive systems "in their own right." The difference is these have a greater capacity for manipulative control and exploitation than do those of non-human Nature, and thus their network character, or soul, tends to act in this manner "of its own accord"--regardless of what we humans assume our systems are meant to do. Thus even human systems intended to act reciprocally with others, to foster the flourishing of other human and even non-human systems, if hierarchically configured, will often tend to act willfully "in the interest of" their own ability to control and manipulate others. This applies to the institutional entities of governments, justice, economy, education, religion, and even of philanthropy or ecological protection. Our assumption that such systems can fundamentally put the "interests of others" above those of their own self-sustaining control functions is not only "dynamically naive," it is producing catastrophic consequences for both our species and life on earth. The Social Organisms of Collective Human Networks What is most significant about these facts of network autonomy is the implications for how we understand motives in human systems. Though it might seem that organizations and institutions are primarily directed by the motives of the individual persons who are in leadership positions, the science warns us that human behavior can be profoundly influenced by the impetus of network autonomy in the system itself. An extreme example of this is the behavior of very ordinary Germans in the extremely immoral operations of the Nazi state--most particularly its orderly prosecution of genocide. Individual human agency can readily be subsumed under the influence of collective network autonomy. Thus it is essential to regard any system that is constituted by collective social networks as a subjectively autonomous "social organism." Doing so enables us to attend to the role collective network autonomy plays in our interpersonal relationships with each other and in shaping events in ways we neither intend nor approve. Further, it aids in discerning what kind of network character is emerging from interpersonal relationships and the ways our systems are configured. To do that requires plotting the actual feedack loops that are forming within these systems and how those are suppressing or amplifying aspects of network behaviors. Exploring the Conspiratorial Creatures of Everyday Networks System networks are usefully regarded as "consipriatorial creatures." That is, networks emerge from a variety of often conflicting impulses within a system, which constitute expressions of "spiritual animation." These "come together" in interdependently synergistic interactions, from which emerge the unpredictable yet effectively intentional behaviors of the overall network. Thus we can seek understanding of our systems through examination of the various impulses arising in their networks that coalesce as overall behavior, in response to varying factors inside and outside the system. What are commonly termed "conspiracy theories" reflexively seek to explain events solely in terms of the conscious intentions of individual persons. Certainly, cabals of people engaged in plotting behind-the-scenes manipulations occur, constituting obscured sub-networks operating within and across social systems. However, in evaluating "hidden motives" in the operations of collective social networks, from street gangs to global financial institutions, it is now scientifically appropriate to investigate these as aspects of motivation in network autonomy formation itself. In other words, social-based system networks manifest "creaturely" intentionality that can be considered to be the "conspiratorial" assertion of a non-human "actor"--or actors--in the form of network autonomy. The more control-oriented the structure of a system is, the more prone its network autonomy is to acting in ways that promote its capacity to maintain and extend its manipulative operations--whatever the values and intentions of the humans involved in it. The hierarchical, control-obsessed networks of institutional systems are particularly prone to manifesting self-promoting network autonomy, regardless of their assumed purposes:

Armed

forces:

Governments:

Financial and commercial corporations:

The salient point here is that we humans, through our interactions,

give rise to system networks that act autonomously in ways we do not

intend or even perceive. Our presumption that only our conscious acts

create the consequences of our systems' operations is dynamical

delusional. "We", in effect, do not know what we do because we do not

understand how network autonomy arises from our actions. Thus we often

do not understand what our actions are actually "in service to."

A further aspect of this ignorance is that when we perceive overt conflicts between social groups, such as political parties espousing contrasting ideologies and policies, we assume these are acting for genuinely different purposes. However, due to the interactive dynamics of such sub-networks within a larger social meta-network, their apparent conflict can become part of a larger scale intentionality on the part of the colelective network's autonomy. That is, evidently competing political parties can serve to facilitate the concealment of the overall network's operations. Liberal and conservative factions can give the illusion that the overall social-political system is manifesting distinctly different impulses when it is in fact acting to enhance the power and influence of an existing elite system of individuals, institutions, and corporations. This sub-network within the larger social meta-network benefit from the perception that there are two competing factions. Thus it will act, our of its own self-interested autonomy, to promote the debate but not allow it to result in any significant changes to their dominance of the larger system. The same obscured effect occurs even in two person relationships where the parties think they are struggling for their contrasting goals but the network emerging from their interactions has the intention of promoting the conflict to preserve the existing form or the meta-system constituted by the conflict. Such is the hidden character of "conspiratorial" network operations within and between social systems. Recognizing the "Monstrosity" of Network Autonomy The mythic notion of monstrosity is useful in distinguishing reciprocally interdependent network behaviors from non-reciprocally exploitative network character. The archetypal traits of monstrosity often involve aggressive, voracious, and anti-social qualities. Thus monstrosity often associates with psychopathic personality, indicating an incapacity to feel empathy or act cooperatively. This aspect of network character is often found in systems configured for competitive and exploitative purposes, which can manifests in spite of human intentions regarding the functions of those systems. Thus systems manifesting monstrosity in the mythical sense are often conflicted and unconscious about their destructive aspects, psychologically speaking. Monsters are real--but they are not things, they are network soul The single-minded, many-headed, life-devouring characters of non-reciprocating network autonomy:

Monstrosity can readily emerge in the network autonomy

of mass social movements, as these arise from from the seething

interaction of many interacting

networks. The self-organizing criticality of such dynamic

interdependency holds many possibilities. But experience shows how

often they either generate conformist enthusiasm, aggressive

competition, and simplistic ideology which can lead to collective

psychopathic behaviors. One the other hand, they often arise in

response to such behavior manifesting within institutionalized social

systems as an impetus toward more reciprocal relationships between

sub-networks in an overall society, such between hierarchically

stratified social classes. In individualistic, heirarhcially

competitive, technologically control-obsessed societies, monstrosity is

a particularly nascent potential in the formation in the archetypal

soul of social networks. The tenor of these networks can readily swing from one extreme to another.

Social and political movements express variable archetypal network soulSocial network impetus toward collective identity and equality prompt a wide range of network behaviors:   Institutional power structures often exploit or suppress these impulses for the sake of sustaining their dominance:   It is dynamically naive to expect control-oriented systems to abdicate their power and resist monstrosity for the sake of enhanced inter-network reciprocity:   The Monstrosity of Individualistic Fragmentation

Confrontation and violence between systems can prompt monstrosityThough contemporary societies express a primary concern about the rights and liberties of individuals, this aspect of network character is also problematic. Our cult of individualism can foster non-reciprocating competition between persons and social groups that fragments network interdependency. This can not only debilitate the operations of society as a meta-system but make it more vulnerable to manipulation by sociopathic or even psychopathic sub-networks seeking manipulative power. Thus, whether analyzing the network character of a two-person relationship or an entire society, one must investigate the complex dynamics arising from every and all system elements and their assumed purposes. Both a marriage and a larger social or economic system configured around competitive individualism can manifest monstrous network autonomy--meaning network intentionality that acts to disrupt the sustainable operations of the meta-system. In this regard, the practice of Scientific Mythology can reveal how the interaction of sub-networks might adjust their behavior to facilitate more sustainable and equitable meta-network operations. However, that means increasing or redirecting flows of feedback among the sub-networks of individuals and various social or economic groups--which means these must become more reciprocally responsive. That is the concept of democratic society. But that concept, and even an existing system structure that facilitates its potential operation, are not the same as effectively activated interdependent feedback loops between a society's sub-networks of social, economic, and political groupings. In short, when the many act competitively with each other, and delegate or concede power and control to a few, manipulative domination by the few is inevitable. Dynamically speaking, that is a recipe for monstrous network behavior on various levels. Evaluating the Catastrophic Potential of Non-reciprocal Network Behaviors Long term sustainability of systems derives from their relatively equitable reciprocity with other systems. Interdependent systems must "give to get." Non-reciprocating exploitation of other systems, whether by individuals or larger social networks and institutions, promotes chaotic dynamics that are not sustainable over time. That is so because it disables the autonomously self-organizing operations of other systems, promoting chaotic dynamics that reverberate through larger meta-networks all the way up to that of the biosphere. Evolution among natural systems constantly imposes relative reciprocity. But human systems evolve with greater speed and through technological leverage that directly manipulates other systems, making these more prone to acting non-reciprocally, thus pushing complex dynamics into catastrophic chaos. So a primary purpose of Scientific Mythology is to identify where and when non-reciprocating network behavior is occurring and what its extended effects are. Of course, elements of conflict and disorder are essential to effective self-organization. The question is when and how are these factors being amplified by feedback loops in ways that threaten overall sustainability and adaptivity of network operations. Nonetheless, even in the realm of Natural systems, their mutually benefiting interdependency evolves over time, through an interplay of both chaotic and complexly self-organizing dynamics. Thus there are inevitably periods of greater disruption as well as more self-similar continuity over time. Humans, however, have the potential network intelligence to regulate their manifestations of catastrophic disruptions. Our network memory, the knowledge of history, provides us with endless examples of the chaotic consequences of not imposing adequate reciprocity upon our selves and our systems. Out of the chaos our behaviors create arise new, autonomous networks. But these can be "monstrous creatures" whose impetus is toward promoting destruction. Mythology is replete with examples, such as the Greek Trojan War or the annihilating family feud of the Pandavas and Kauravas in the Hindu epic The Mahabharata. that is a "creature of chaos" in its own right Goya's "Colossus"--the "network soul of war":  Discerning the Subordination of Mythic Symbolism to Control Oriented Social Purposes Understanding the role of mythic imagination, as metamorphic transformations and magically creative spiritual animation enable perception of complexity's dynamics, requires differentiating this function from its other uses in social systems. Throughout history, mythical symbolism has served multiple purposes within societies. In its references to spiritual animators, it provides an external basis for spiritual and religious traditions that link human consciousness and identity with the purposeful forces of the non-human world, and thereby creation itself. By this orientation it, provides a common cultural language for collective identity. In these regards, it imputes a more meaningful sense of identity and purpose to both individuals and collectives by connecting them to a similarly conscious and intentional cosmos. These functions also serve to validate the subordination of individuals to the structures of social orders, by linking social practices and customary roles, such as those for men and women, to the spiritual realm from which all is assumed to derive. This latter function is extended to the justification of the inequities of power and wealth in the class systems of hierarchically structured societies, such as civilized states. In all these social and cultural functions, mythic symbolism is effective because it models the mysterious order creation of chaotic and complex dynamics, which are regarded as the "realm of the sacred." However, when employed to justify the inequitable dominance of elite sub-systems within society, the power exercised over ordinary society by the likes of religious institutions, political leaders, and aristocracies is justified because they are posed as, in some way, ordained by or "closer to" the "more than human" sources of spiritual power. When employed for this social purpose, mythical symbolism tends to become regarded as literal, even historical fact, the definitions of which are established by an orthodoxy that is determined by institutional authorities. Elites, in effect, expropriate the significance of myth's symbolism of complexity's spiritual mystery for the purpose of justifying their sub-network's exploitative dominance over the rest of a social system and its meta-network. Of course, brute force often serves to secure the dominance of social elites. But mythological justification is typically employed in some form for this purpose, indicating the intuitive potency of mythical symbolism as reference to "how the world is actually created." Though the modern world is ostensibly secular and holds a primary belief in mechanistic causation as the sole source of all phenomena, rather than a spiritual source, it actually continues to manifest mythical symbolism. The validity of any inequitably hierarchical social system necessarily requires justification in reference to some "greater purpose." That can be the supposed divinity of a king or of a secular nation state as the de facto "sacred spiritual identity" of its subjects. Whereas pre-modern societies referred to a spirit world of gods that were their source and to which they owed their existence, Modernity refers to mechanistic physics and the ideals of humanistic values. Since physics is believed to disprove the existence of spiritually animating divinities, the humanistic values of individual liberty and rationalism constitute the overt justification for social orders. These idealized egalitarian values have come to justify the existence of social norms and their network behaviors. But in so far as they refer to the subjectivity and agency of individual persons, they are mythical references to spiritual animation. Thus the ordering and constraints of a collective society are justified because its operations serve the autonomous existence of the spirit of individuals--despite the fact that these are not overtly regarded as mythological beings. However, this same value is employed to justify hierarchical social and economic stratification that grants some individuals more liberty, wealth, and power of control than others. Thus the actual systems and network operations of modern society are often in conflict with the mythically spiritual references used to justify its existence. The mythical symbolism of the "sanctity" of the self-animating individual, of its liberty and equality, are being subordinated to the justifications of inequity. Thus control-oriented, power-obsessed sub-networks can act to exploit the larger system in non-reciprocal ways, for their own inequitable advantages, claiming to be doing so in service the the spiritual basis of the social order. The inequitable advantages of elites are presented as promoting the society's purpose of serving the spiritual individual while acting to exploit it. Mythic Symbols of Social Purpose and Authority

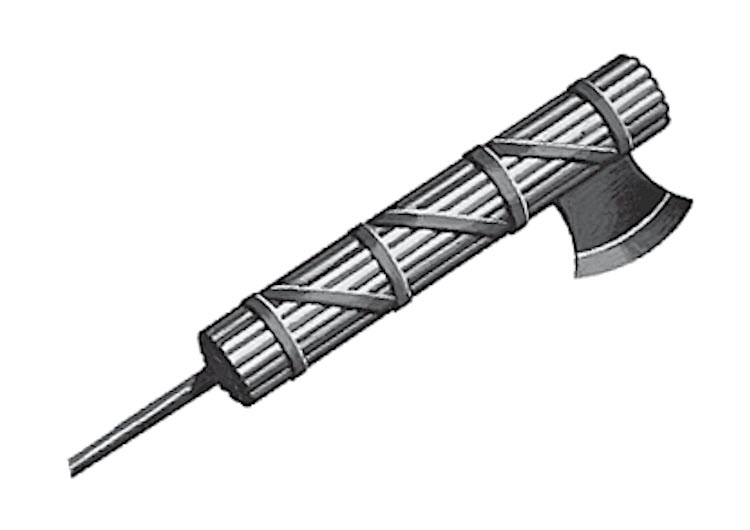

References so "spiritual forces" that justify social power Royal crown with cross: Roman/Fascist faces: National Socialist Eagle:    The royal crown of European kings was often topped by the Christian cross, a sign that the king was the channel through which god acted in the world, justifying personal actions regardless of the consequences. The Roman faces, a bundle of sticks bound together around an axe signified the unity of the many bound closely together and the power of its commanding social hierarchy over life and death. It was used in the 20th century as a symbol of political fascism. The Nazi movement in Germany combined the eagle that symbolized the preceding imperial state with its expropriation of the ancient swastika, once an auspiscious symbol of life's order emerging from chaos, to represent its triumphant right to conquer and rule all other systems in the name of a superior ethnic Germanic "spirit." All these symbols indicate that the many of society exist for the political state that personifies their values and purposes. Social Rule in the Name of Spirit

God-king Pharaoh: Divinely

guided pope: Spirit of