| Discover the Reality of Scientific Mythology The Facts of Self-Animating Networks in Nature and a New, Realistic Role for the Mythic Imagination

|    |

> NOTICE: This website represents in a work-in-progress. Please contribute your feedback! email link <

| Home Page | What Is Mythic Imagination? |

|

|

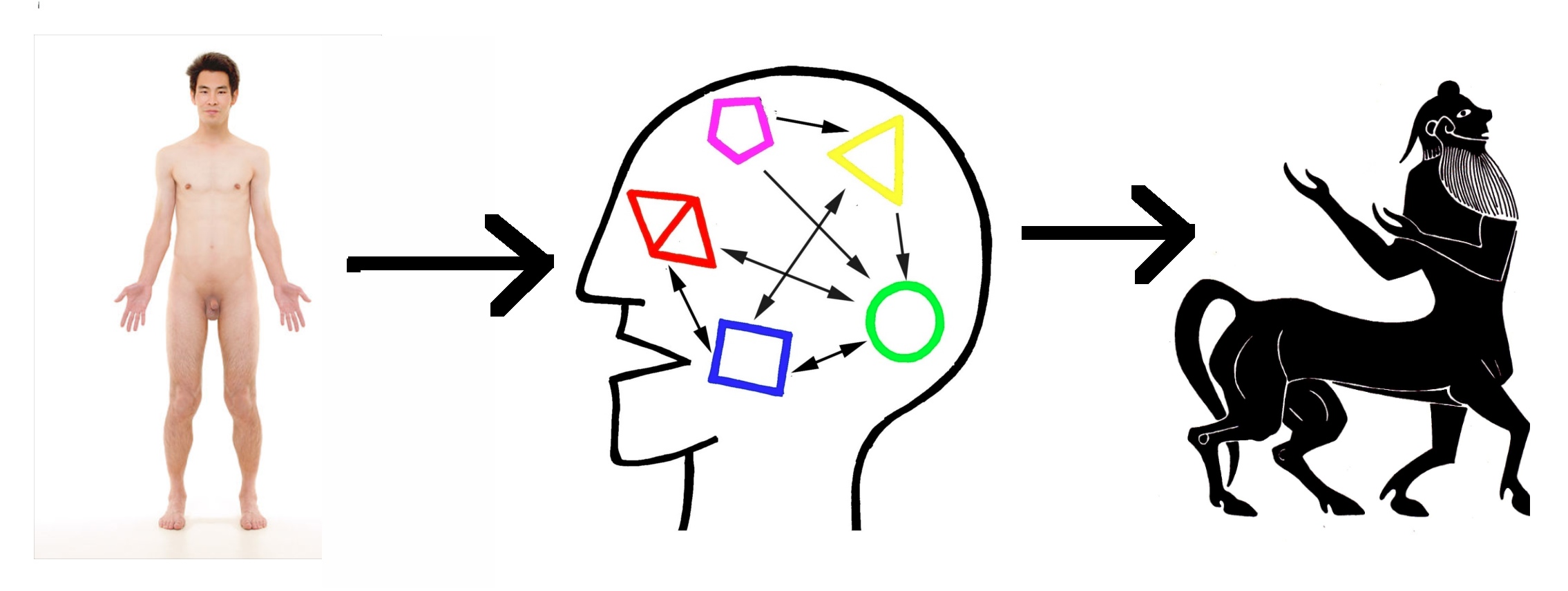

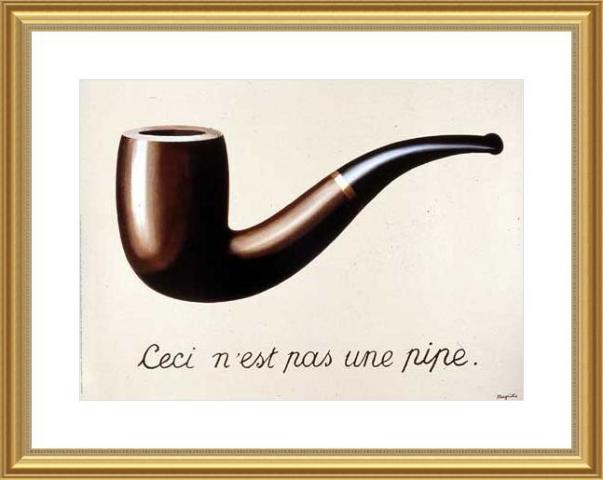

The Dynamical Modeling of Mythical Symbolism and Its Scientific Basis Bottom Line: 1.Metaphoric symbols function as constellated networks of interdependent complexity: Symbols represent something they are not. Metaphors combine familiar aspects of reality in illogical or unrealistic ways: "John is a wolf." Such paradoxical associations cannot be logically sequenced or explained. Their elements only make meaning as constellated networks. This nonlinear association models complexity's interdependent dynamics. 2. Mythic imagination symbolizes through magical events and mysterious agency: The most basic trait of mythology across cultures is the representation of magical transformations and the influence of spiritual forces on the familiar physical world. This motif in the stories, images, and characters of mythic imagination represents an ethereal "other world" of strange dynamical activity and intentionality. 3. Network Science reveals mythic imagination as dynamical modeling of complexity: Viewed from the factual perspective of network science, the magical events and spiritual entities of myth correlate with complexity's emergent creativity and network autonomy. Mythic symbolism models the bi-dynamical order creation of the biosphere. |

|

> Summary Overview < The Mythic Symbolism of Two Dynamical "Worlds"

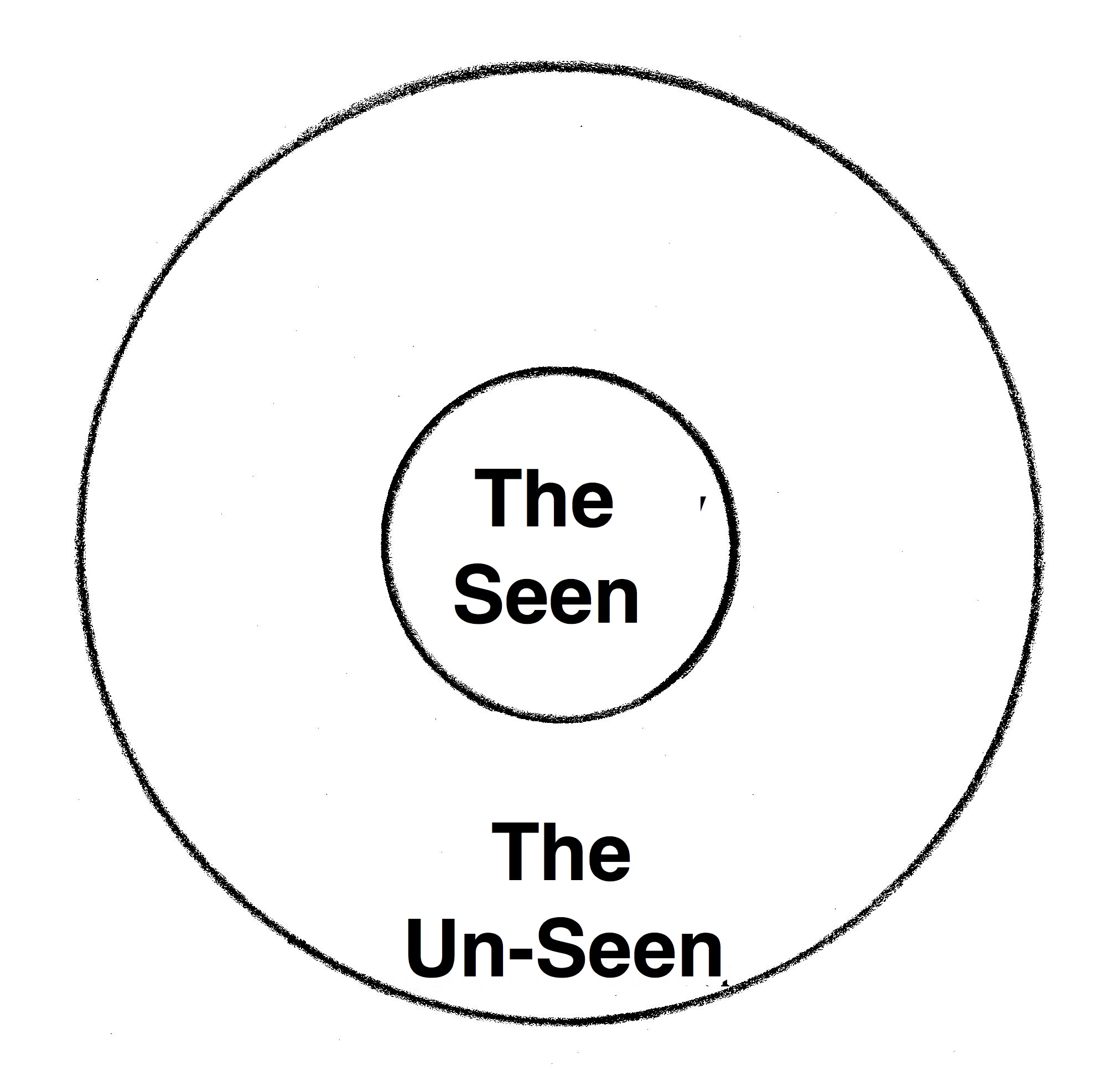

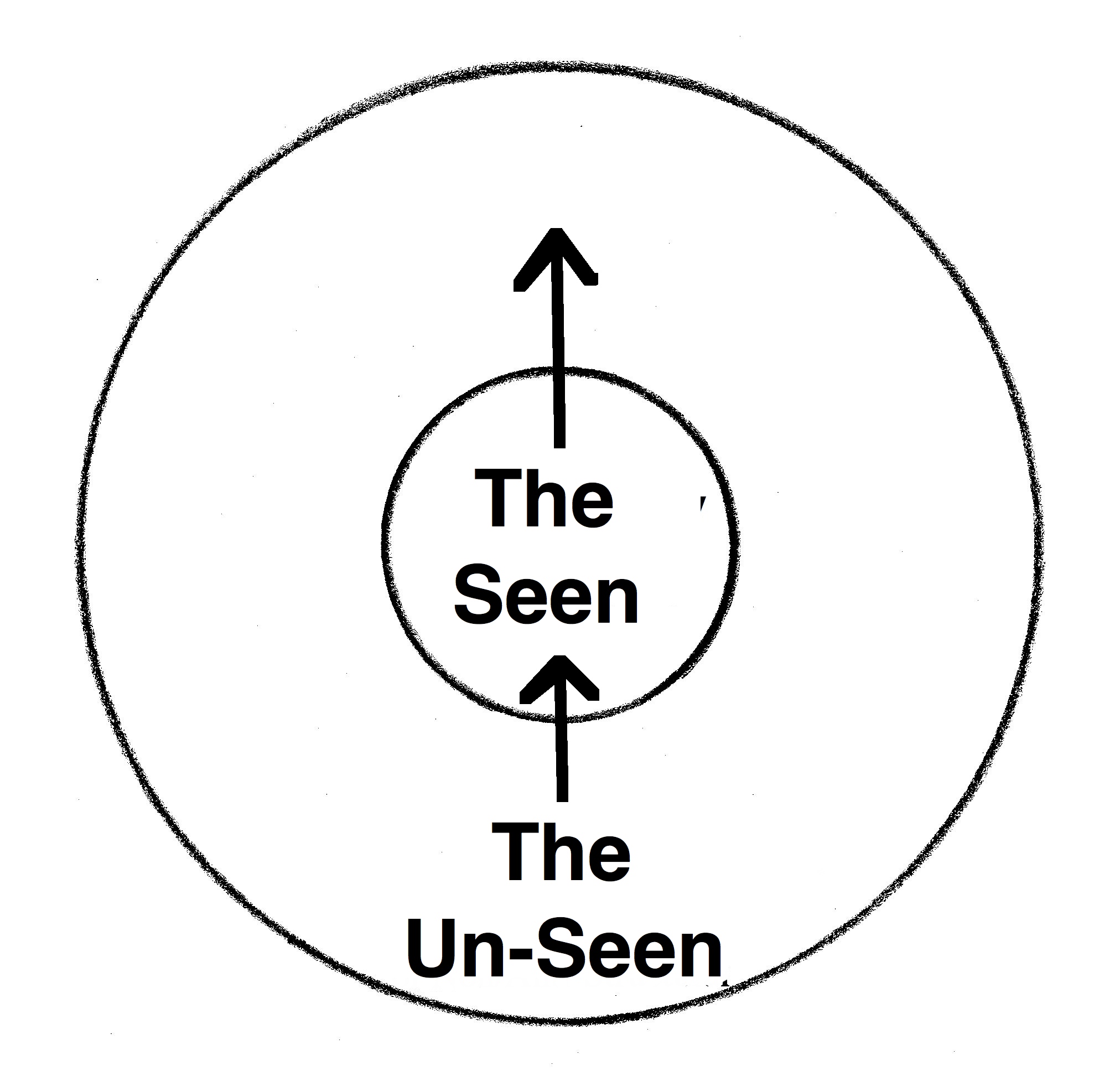

The ordinary physical realm of reality is created and maintained by the spiritual animators of an extra-ordinary one In Myth there are two Ways that Things Happen

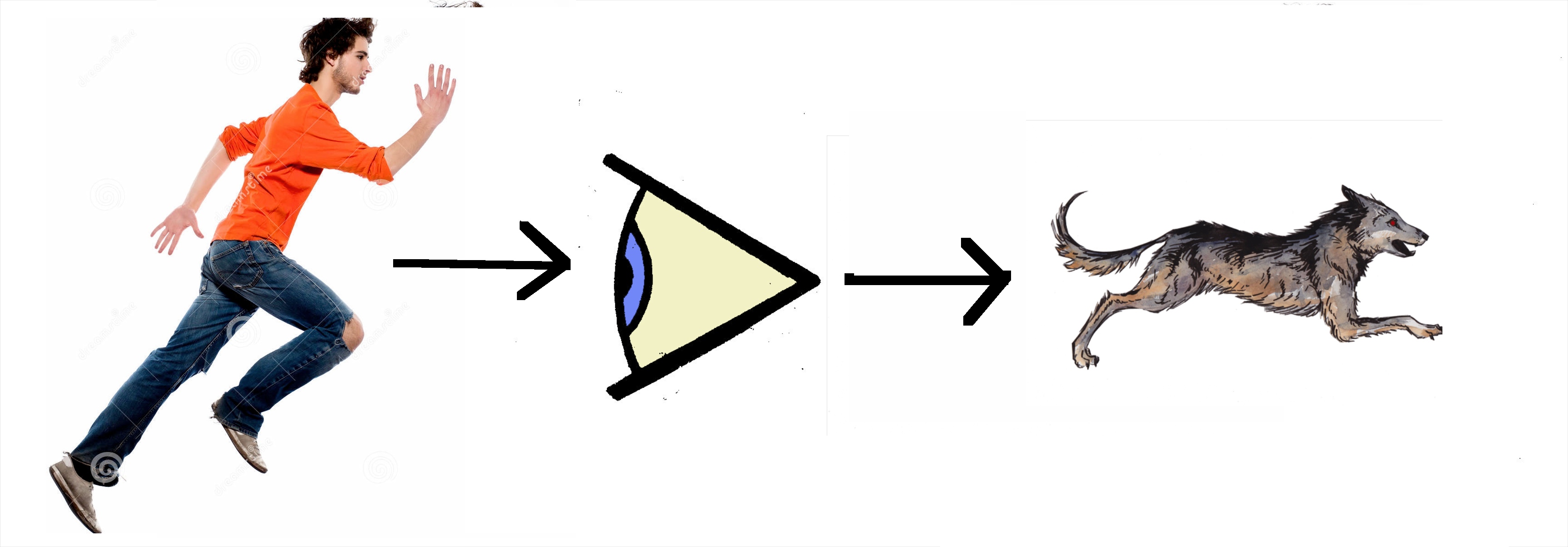

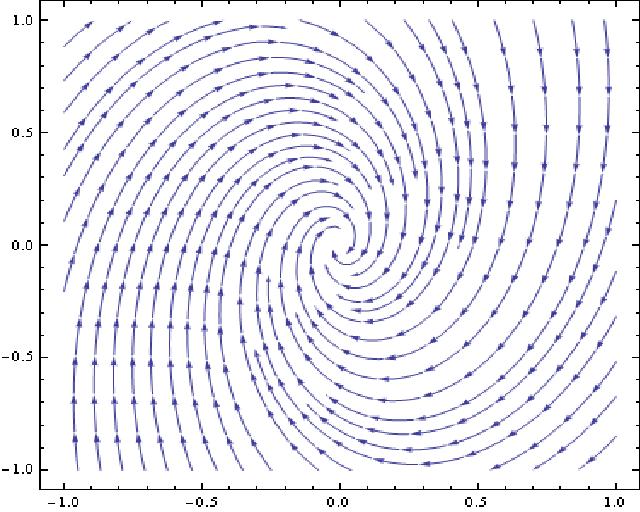

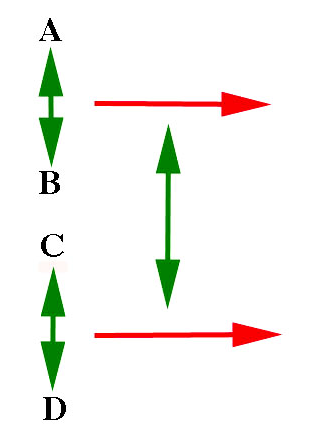

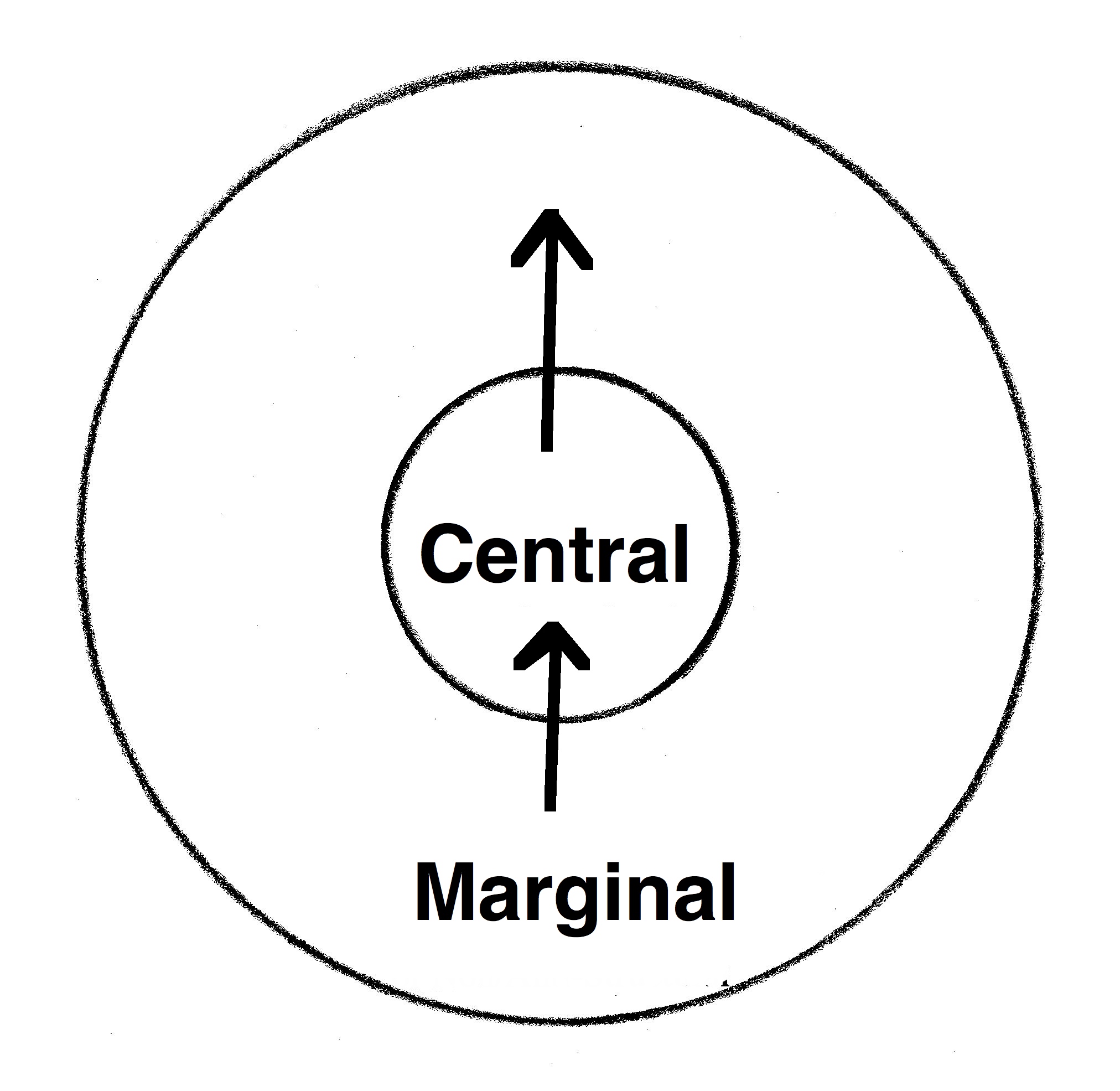

We are all familiar with an ordinary world where tangible things can be manipulated and controlled. That is the basis of our practical view of how to make things happen and act to survive. But where the mythic imagination is active in humans, an additional, very different way that things happen is represented. In the mythic perspective, the practical aspect of physical reality is animated by an "other word" of spiritual forces that have extra-ordinary powers of creation. In this spiritual domain, events are magically transformative and ethereal forces intentionally influence the ordinary realm in mysterious ways that are beyond control. It is these strange events and spiritual forces that make the other world mythical. The physically controllable ordering of "This World":

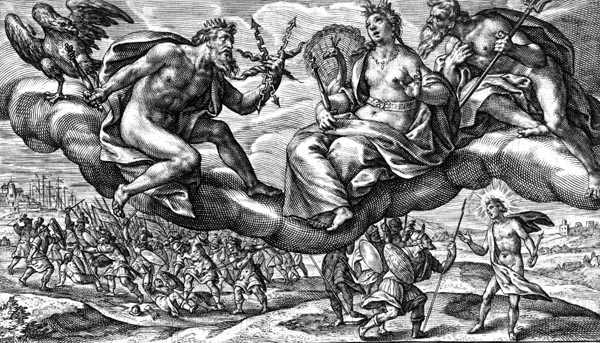

The uncontrollable, spiritual ordering of "The Other World":     In mythic images and stories the ordinary becomes magical. Humans find

themselves confronted with fantastic events they cannot survive, much

less control, without the assistance of the mysterious powers of

extra-ordinary beings. Spirits, talking animals, ghosts, gods, and

goddesses appear to make things happen that appear impossible to our

ordinary sense of reality. Yet their existence and strange influence

are represented as essential to the existence of the world and

the ability to humans to exist in it.

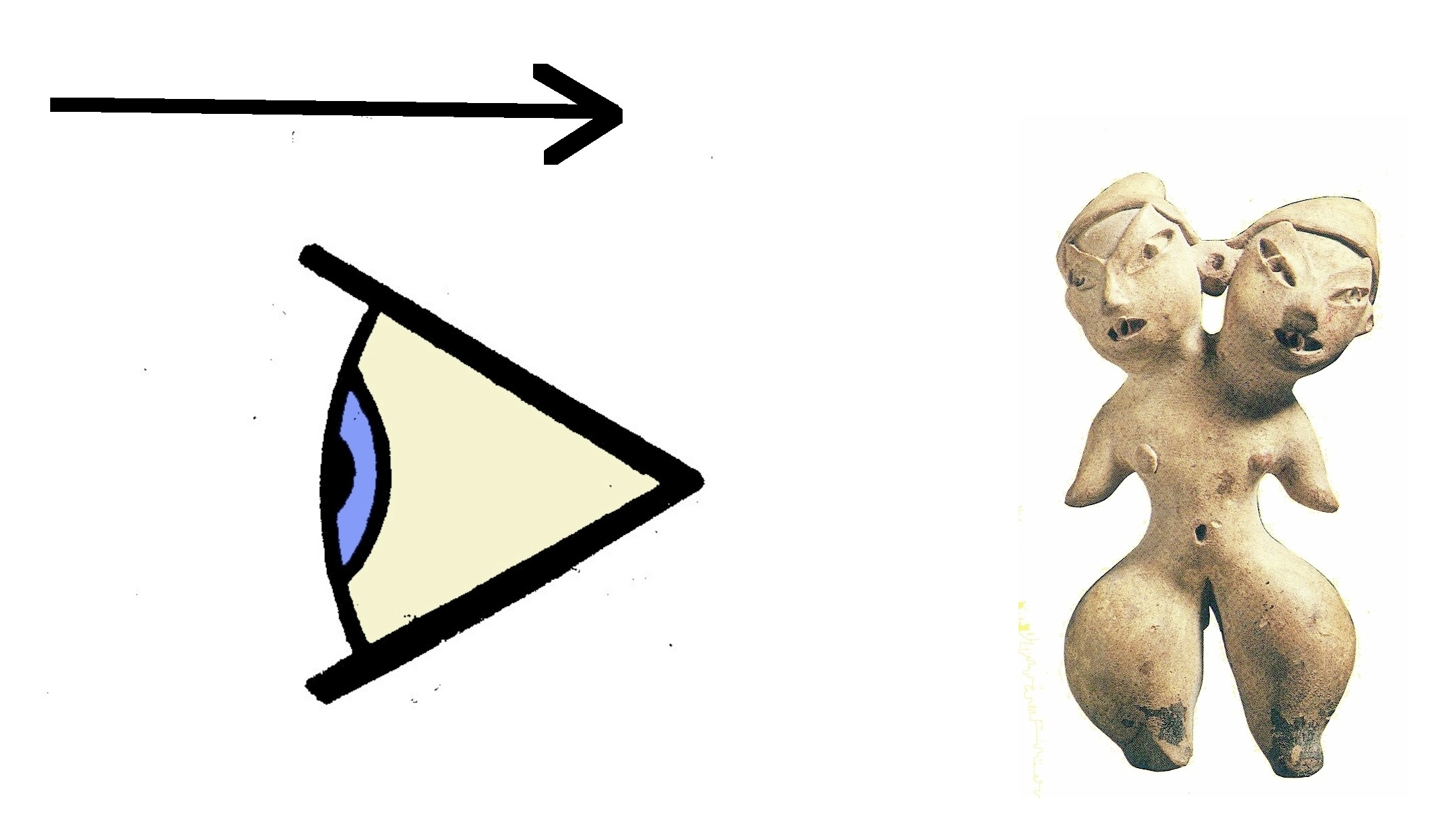

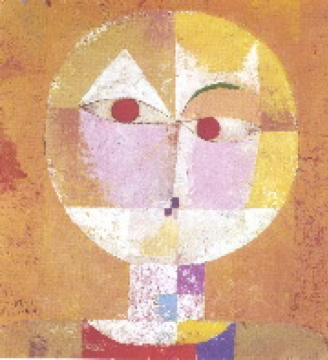

The Doubled Vision of Mythic ImaginationSymbols of Second Sight

The multiple perspectives of Hinduism and the Buddhist third eye of enlightenment:   From Frivolous Fantasy to Factual Symbolism:

Correlating Bi-Dynamical Order Creation in Science and Myth As fascinating as this notion of a mystical "second sight" may be, myth has been regarded as delusion and fantasy by the modern worldview. There has been no category for it in our physics-based definition of reality. But now there is new scientific evidence indicating that myth's "figments of the imagination" are actually symbols of factual events. Complexity science reveals order creation that is obscure to our cultural notion of purely physical science. When scientific method is focussed upon the wholes of complex systems, such as compose our biosphere and human society, a second mode of order creation becomes evident. There is now evidence for two different ways, two dynamical modes, in which the forms of things and events become ordered: the familiar one of mechanistic sequences and the mysterious one of emergent transformations. Surprisingly, this new bi-dynamical scientific perspective on how things happen correlates with the worldview of myth. Science and myth now share a dynamically doubled vision of order creation. From this perspective, we can understand how mythic imagination serves to join our ordinary mechanistic view of the world to an extra-ordinary, seemingly magical one: mythic symbolism models the emergent dynamics revealed by complexity science as an "other world." Myth and science represent the same two dynamical modes of how things happen. There is a Science of Myth's hidden Other World

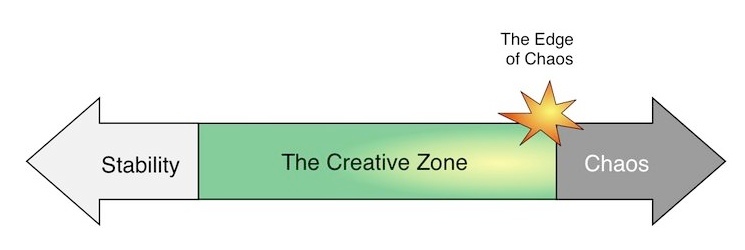

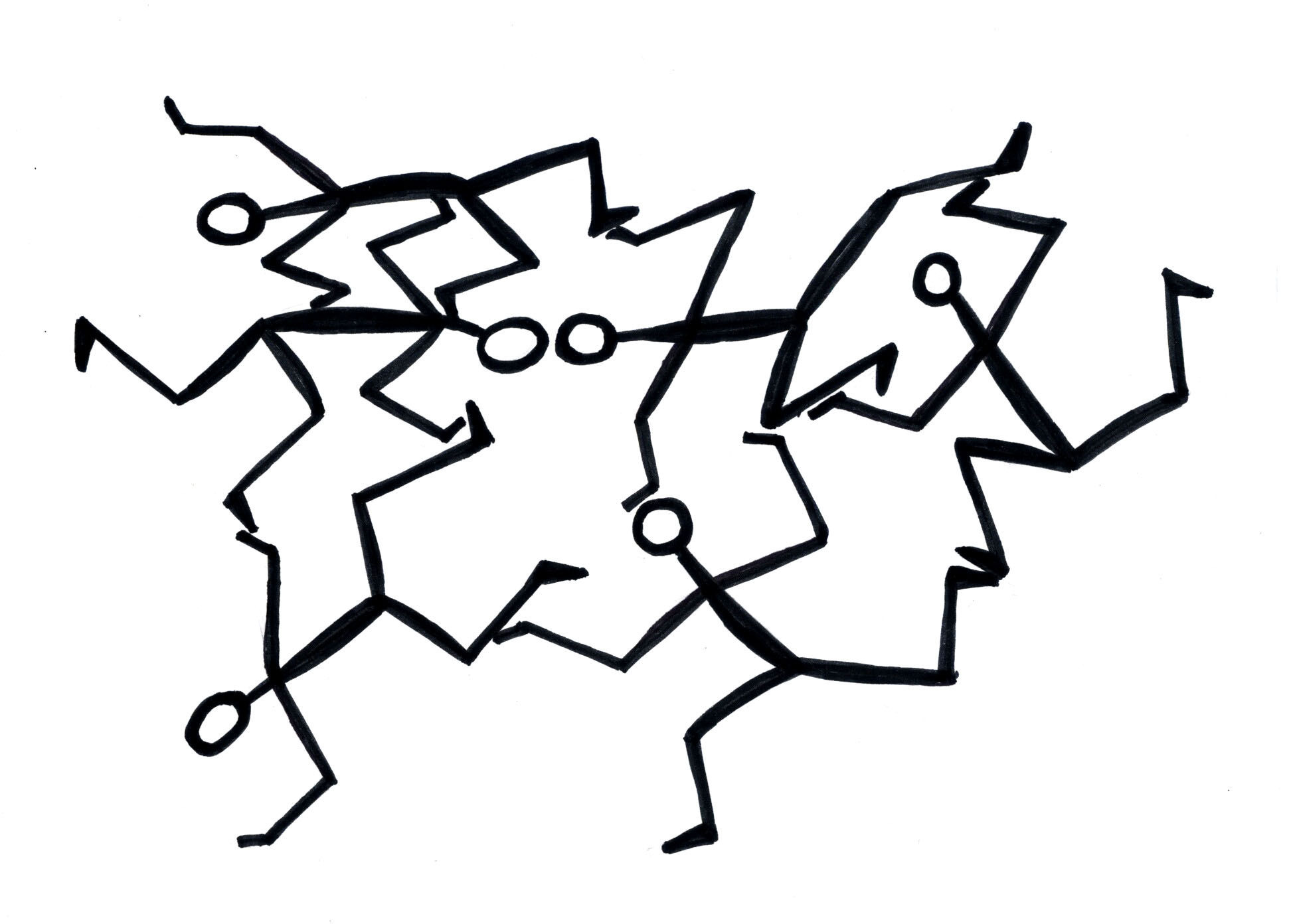

The science locates the

emergent creativity of complexity's dynamics "at the edge of chaos."

This condition of disorderly, unpredictably self-organizing activity is

the real world domain of myth's "other world" of magical

transformations, animating

spirits, and divine powers. There is a basis for a practically

useful, secularly spiritual, meaning enhancing cultural change in

worldview. In complexity science, interactions between unpredictably autonomous networks, like people, create additional autonomous networks with their own character and influence. Mythic imagination gives us vivid, compelling ways of perceiving such phenomena that science cannot provide. Myth makes these ethereal networks "visible." The corresponding bi-dynamical perspectives on order creation in science and myth:

Science

Myth

Physics:

This World:

> Order of predictably deterministic mechanism > Order of practically controllable events Complexity: The Other World: > Order of unpredictably deterministic emergence > Order from uncontrollable spiritual animation Metamporhic Emergence and Complex Networks in Science and Myth

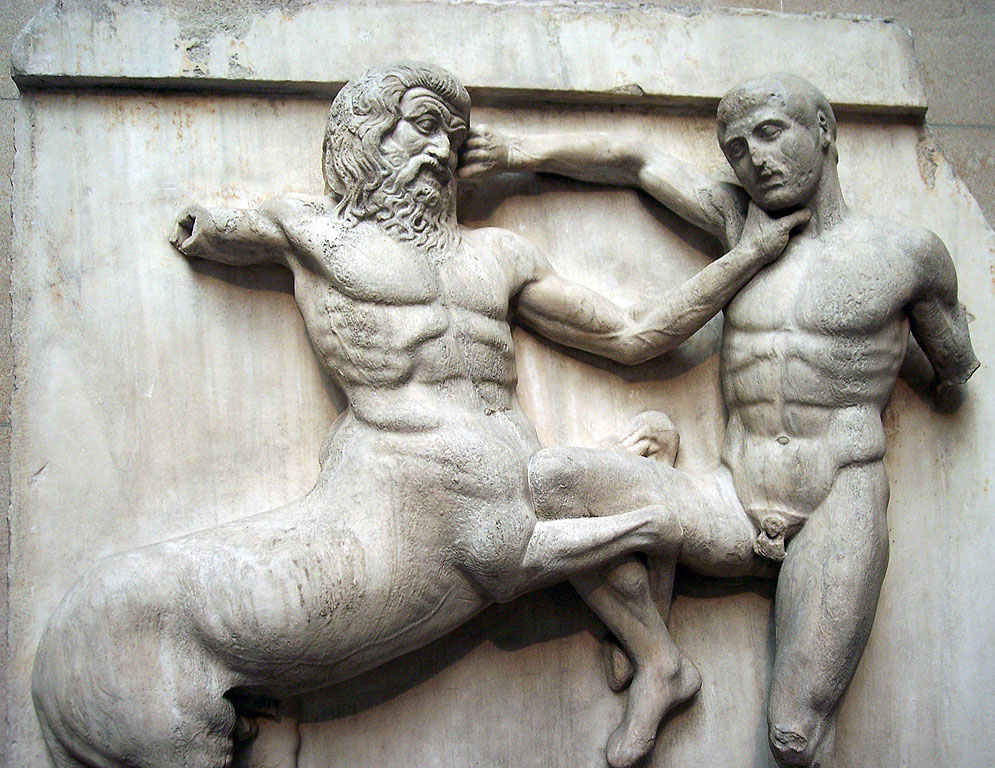

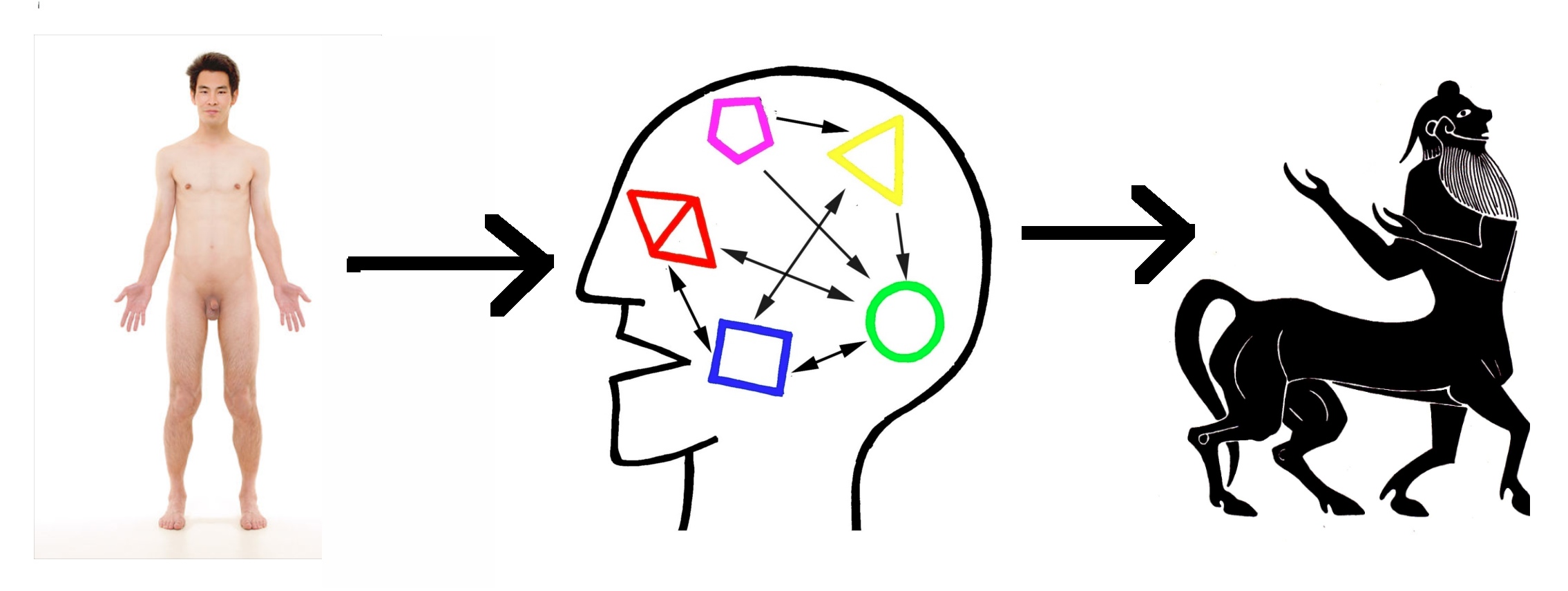

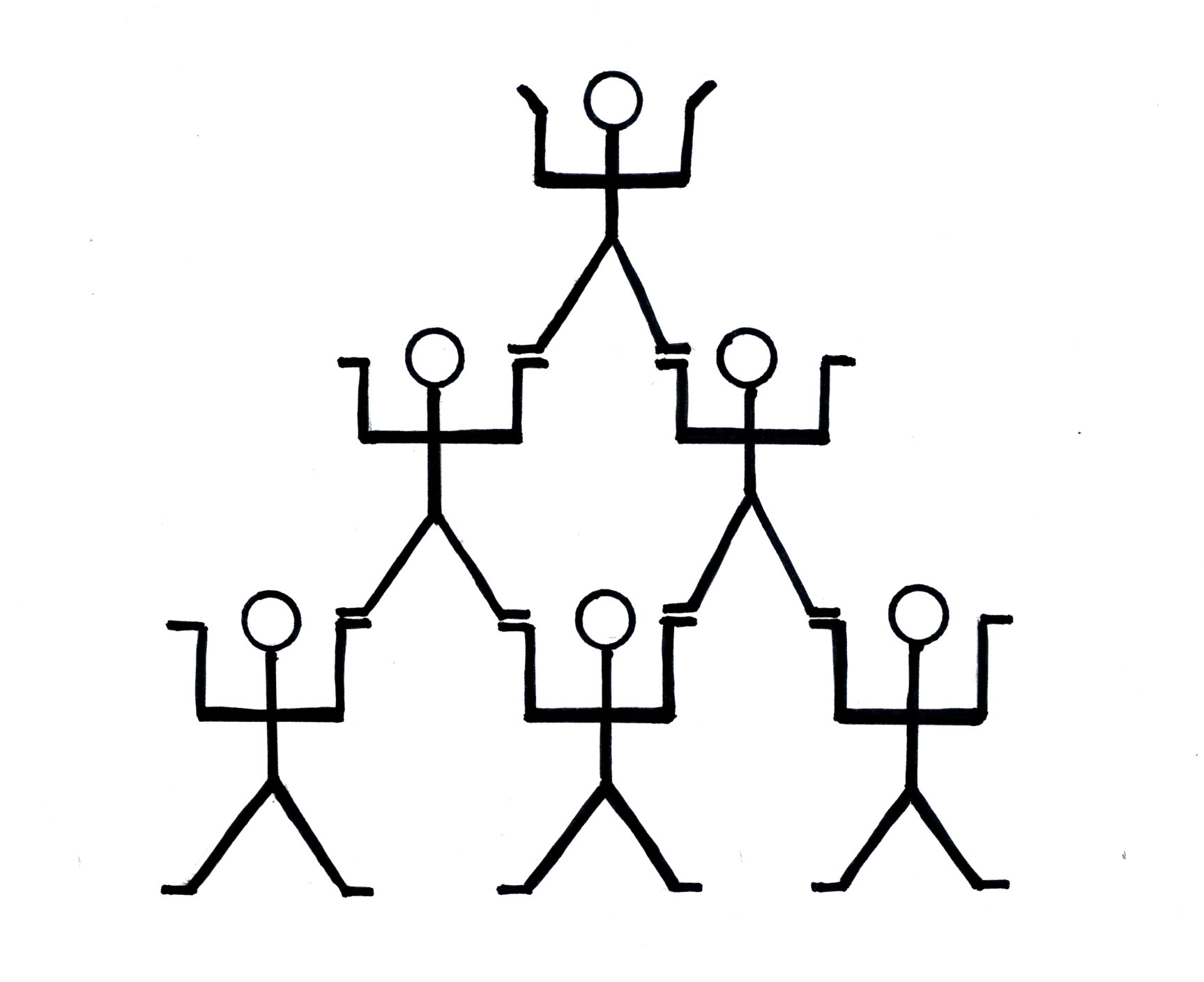

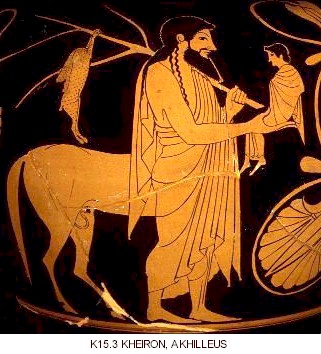

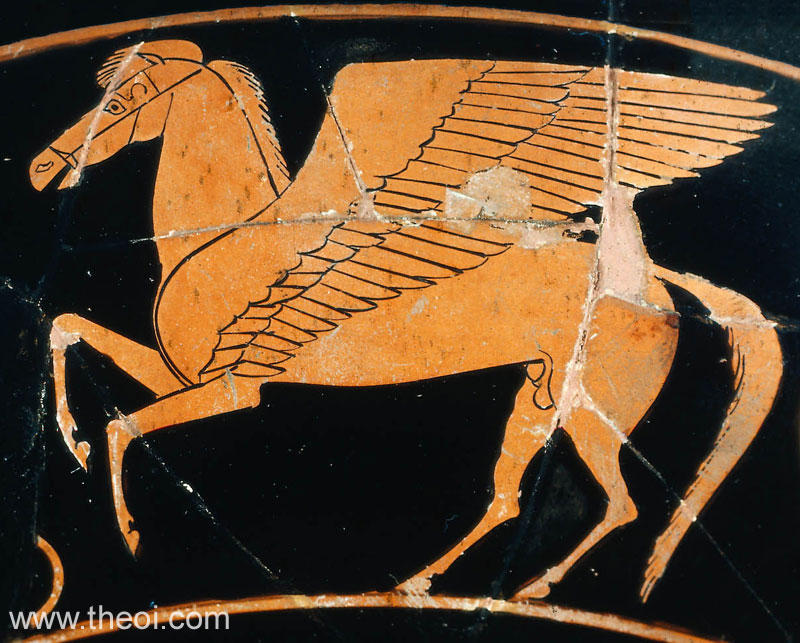

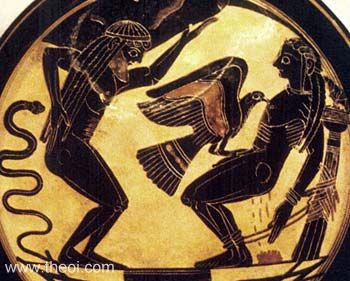

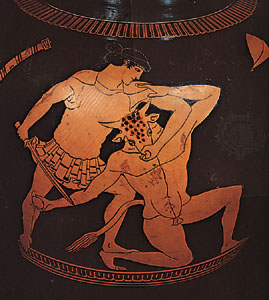

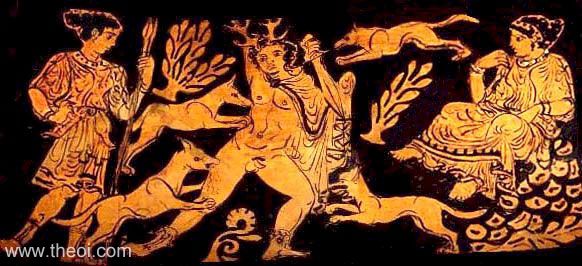

The unpredictable, inconsistently transformative effects of emergent order creation described by science are represented in mythic imagination as metamorphic changes. One type of thing inexplicably becomes another or is composed by ordinarily different things: humanness is metamorphosed into centaur-ness. This metamorphism is the most apt representation of emergent order creation in science. Mythic imagination models the complex, self-organizing system networks of science through the paradoxically nonlinear interdependency of its symbolic images and stories. Its spiritual agents that animate the world "make visible" the variable character of self-organizing network autonomy. Mythic symbolism is the archaic from of "network vision." These correlations are the basis for a practice of scientific mythology, in which the evidence from complexity and network science are amplified by the archetypal symbolism of mythic metaphor. Scientific method takes us to the point of understanding the limits of its ability to fully describe and explain complexity, emergence, and net autonomy. Myth gives us the capacity to represent what science cannot--the variable archetypal character of network autonomy gets expressed in complex systems as an animating force, and how these influence our actual lives. Spirits, Gods, and Goddesses of Myth are the Animating Agents of

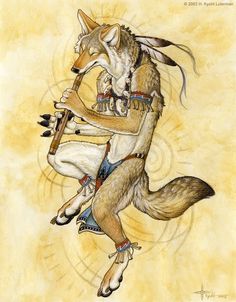

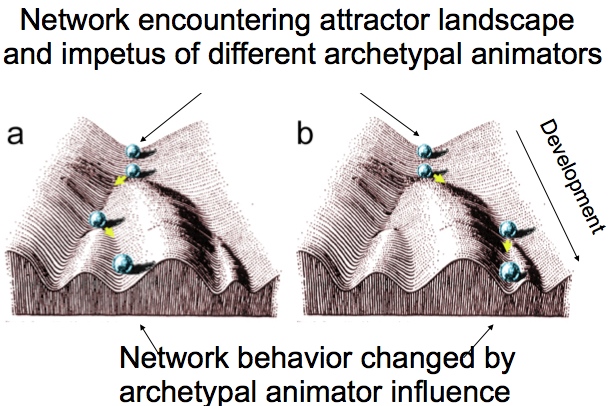

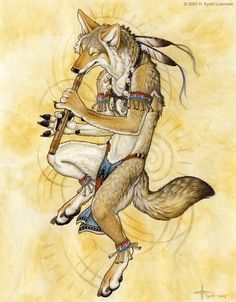

Network Autonomy in Science The spiritual animating agents of myth, its spirits, gods, and goddesses, can be understood as archetypal forms of influence that shape the behavior of network operations in actual systems. These archetypal animators tend to be depicted as complex psychological characters in and of themselves. They also are shown to have characteristic, on-going relationships with each other that suggest commonly occurring constellations of network behavior in Nature. Rational Apollo: Ecstatic Dionysus: Trickster Coyote:

The

interactions of thes archetypal tendencies effect the ongoing changes

in emergent order creation. At any given moment, they are acting in

networks of interdependent relationships that constitute the

"con-spiracies" of a meta-network system. The notiin if various

"spirits" interacting represents the contrasting impetus emerging from

a comple network as it self-organizes or self-animates.

Myth Imagines the Archeytpal Animation of Network Soul

Through careful observation of the order and behavior complex systems manifest, mythic imagination generates metaphoric images and stories that symbolically model the autonomous behavior of complex networks. These symbolic models characterize the archetypal traits of the dynamic patterns of particular systems and how they interact with other systems. These imaginal representations give us an intuitive sense of how events take place and systems act that science cannot provide. Mythic imagination reveals hidden factors in the networks of our personal relationships

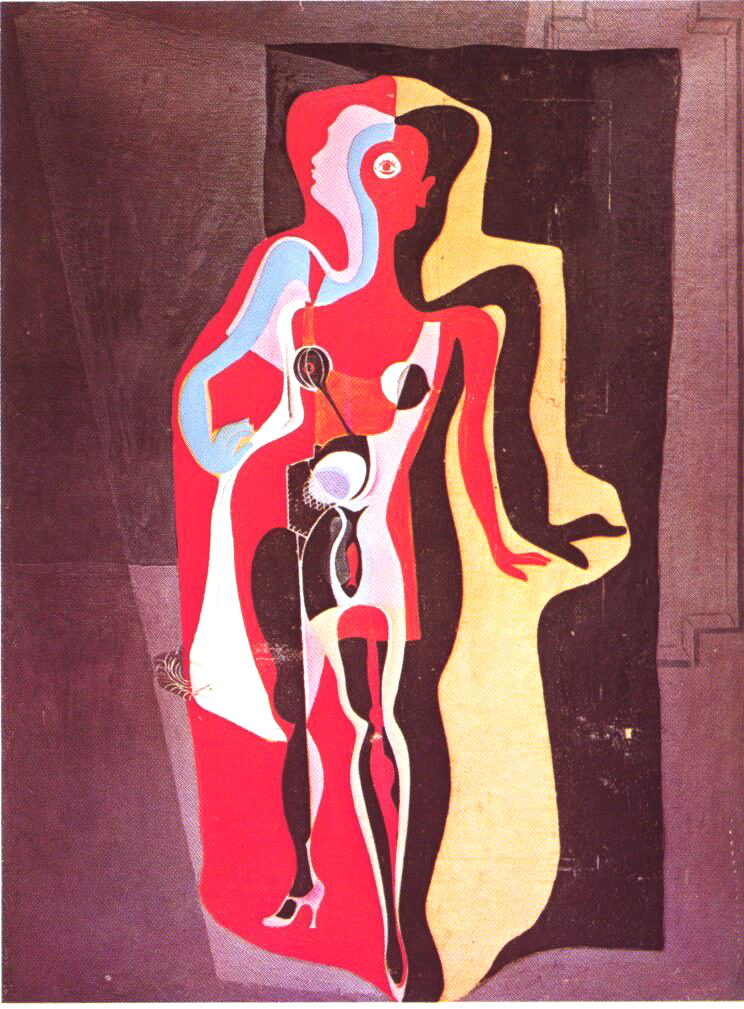

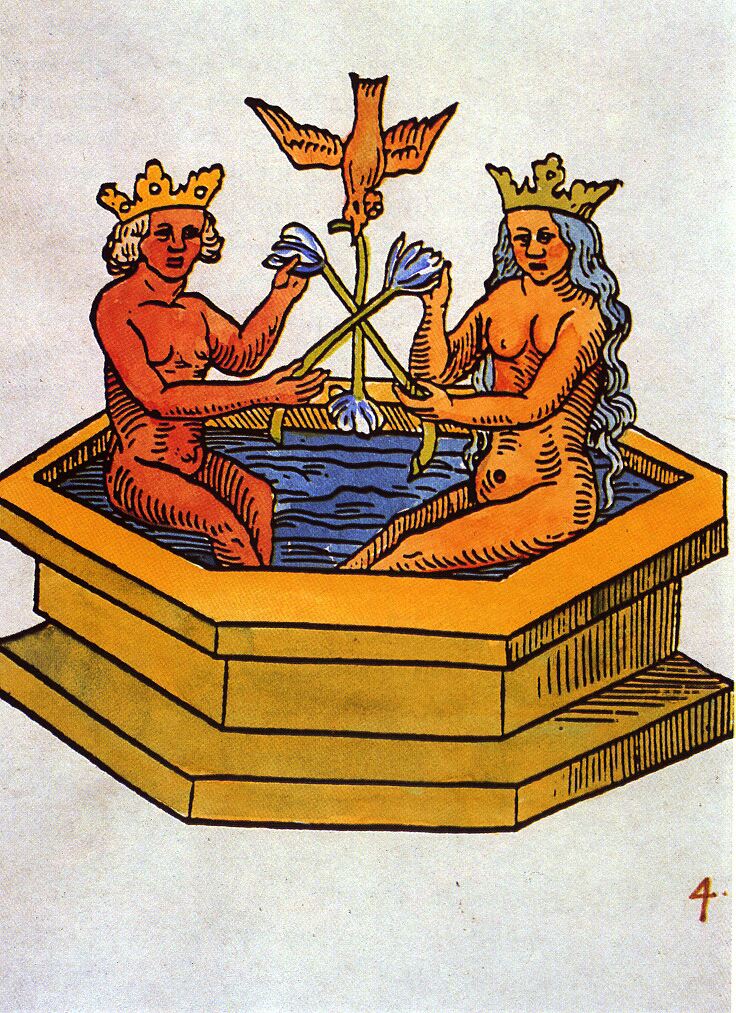

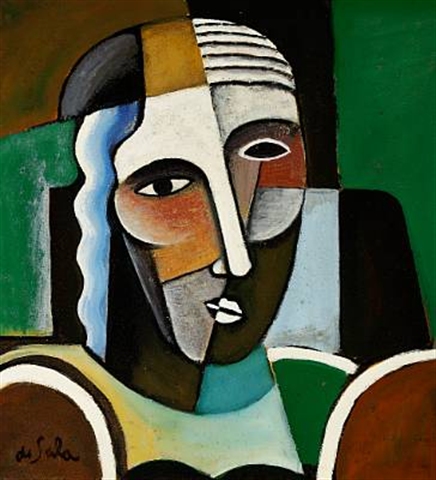

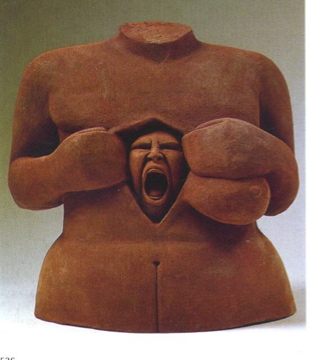

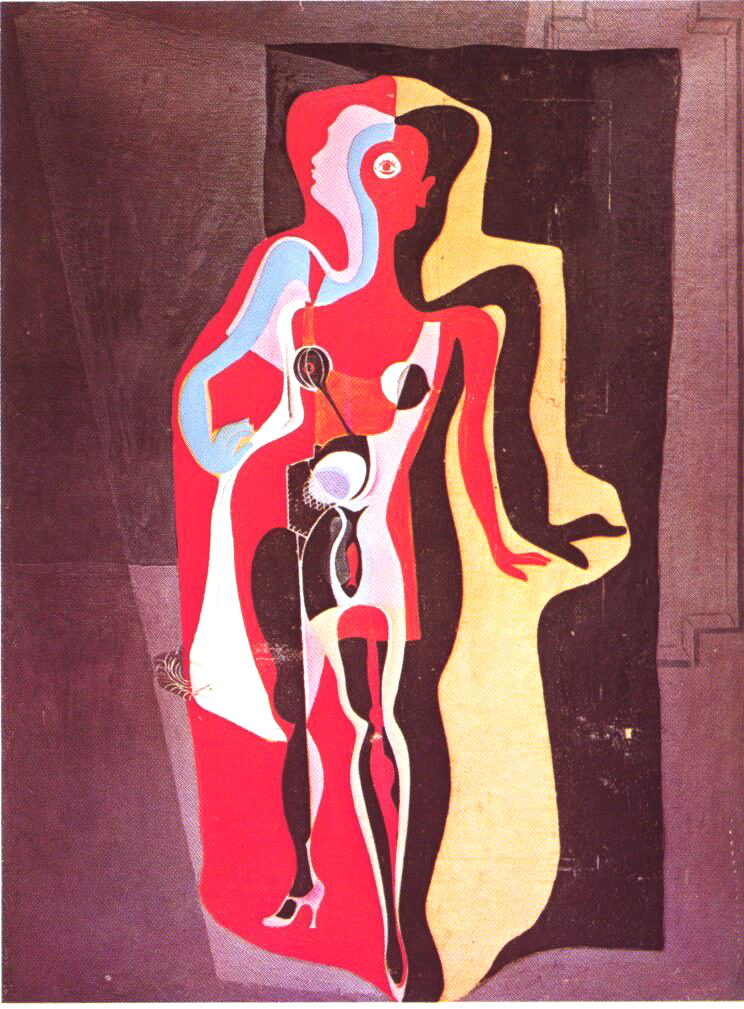

The struggles of gender seen through the Third Eye of Mythic Imagination:    Mythic metaphors reveal the behavioral character or personality of network self-organization in particular systems by representing its fundamental or archetypal traits. In this way they provide an archetypal psychology of how network autonomy animates the world, of the ways it becomes the "minding of matter"--in human and non-human systems. By imagining these behavioral characteristics in a metaphorical mode of representation, the self-ordering individuality of a system is revealed as its network soul. Making the character of network autonomy visible

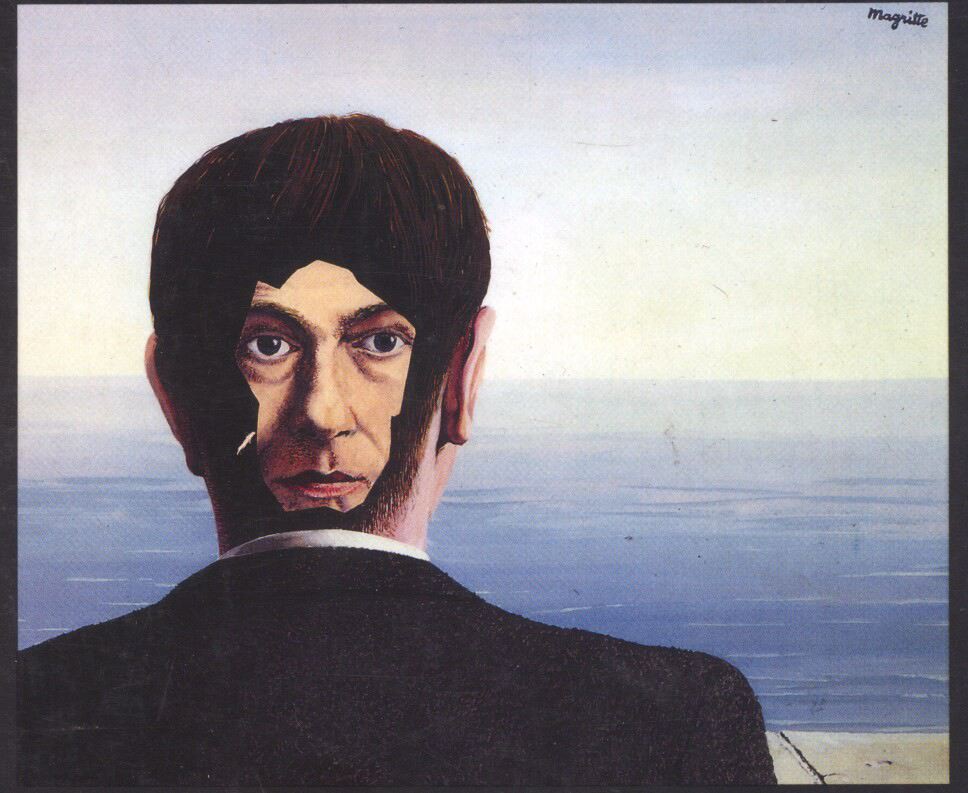

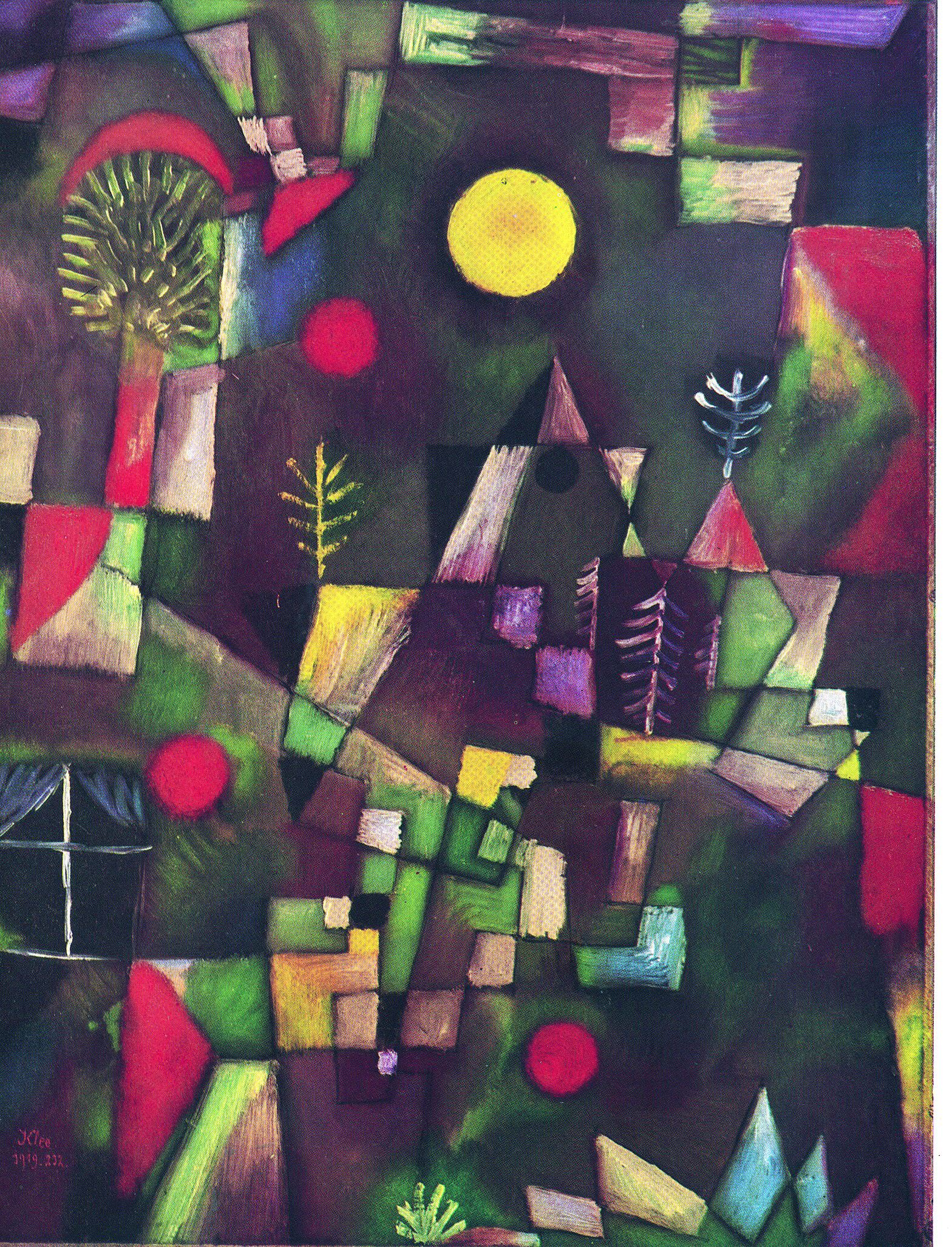

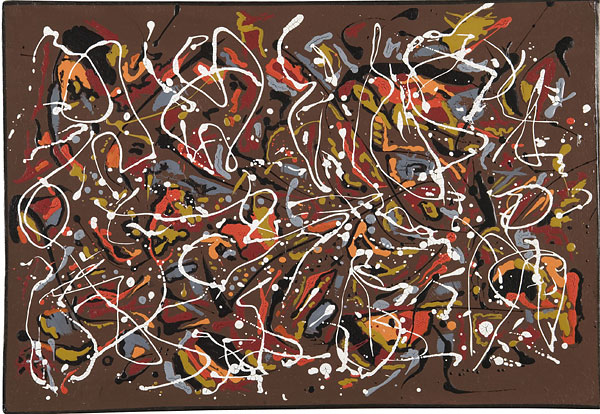

The archetypalizing imagination of network soul:  The Mythic Imagination of Perceiving Bi-Dynamical Realty in Art

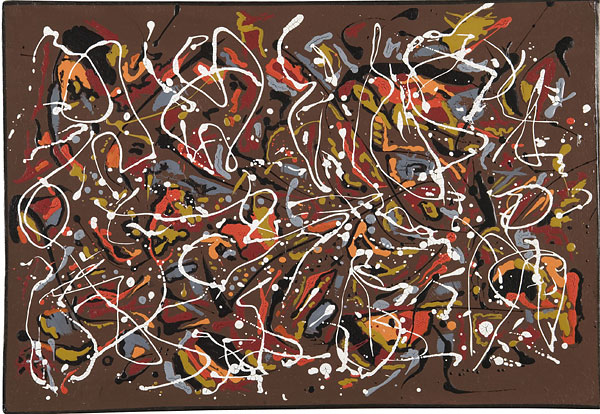

The correlations between complexity science and mythic symbolism provide a new understanding of the imaginal reality of art and literature in general. It becomes evident that artistic expressions are also a form of myth's "third eye" and "second sight" into a bi-dynamical reality of mechanistic and emergent order creation.

Understanding Mythic Imagination as Symbolic Network Science Contents Below with Links:

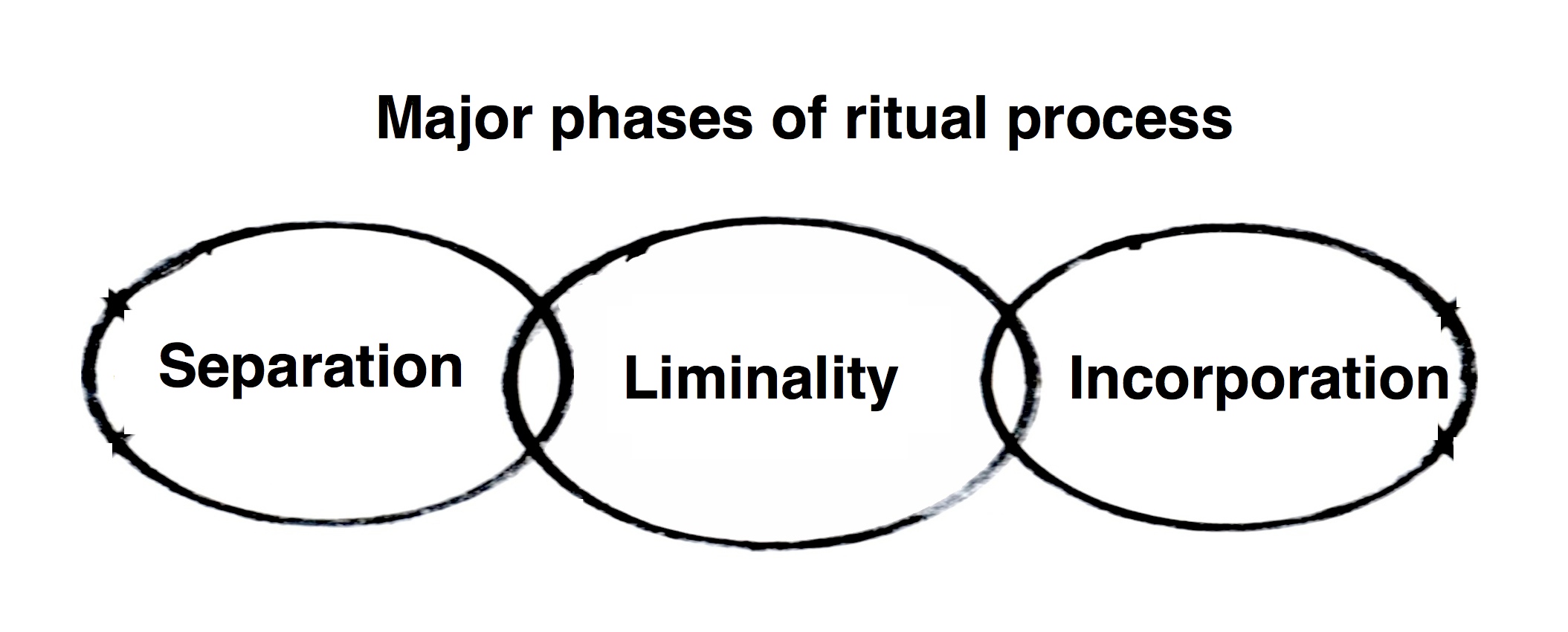

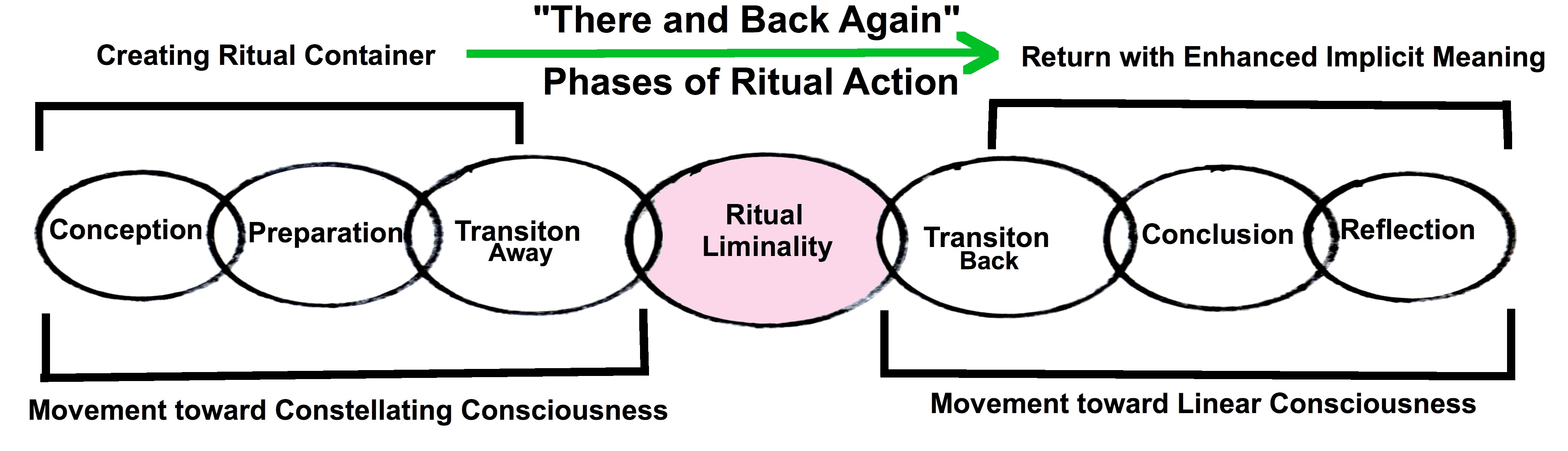

> What is the Mythical Imagination?> New Disorderly Logic of Networks and the Validation of Mytho-Logical Reality > Correlating Complexity and Network Science with the Dynamical Modeling of Myth > Mythic Symbolism as Archetypal Complexity's Emergent Order and Network Autonomy > Myth is the Archetypal Psychology of how Network Autonomy Animates the World > Archetypalizing the Psychological Identities of Spiritual Animators > Archetypal Spiritual Animators as Dynamical Attractors > Exploring the Dynamical Attractors of Myth's Other Worldly Spiritual Animators > Telling the Story of Emergence and Network Autonomy Archetypally > Variations of Mythical Narratives > Mythic Themes of Metamorphic Transformation > Rites and Rituals: The Symbolic Gestures of Engagement with Network Character > Activating Experience of Spiritually Animating Networks through Ritual Symbolism > Ritualized Meditation and the Induction of Liminal Consciousness > Mythologizing the Archetypal Network Dynamics of Human Psychology > Mythic Imagination in Social Order, Spiritual Practices, and Religion > The Mythologizing of Secular Art

What is the Mythical Imagination?

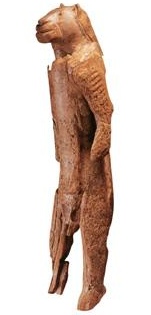

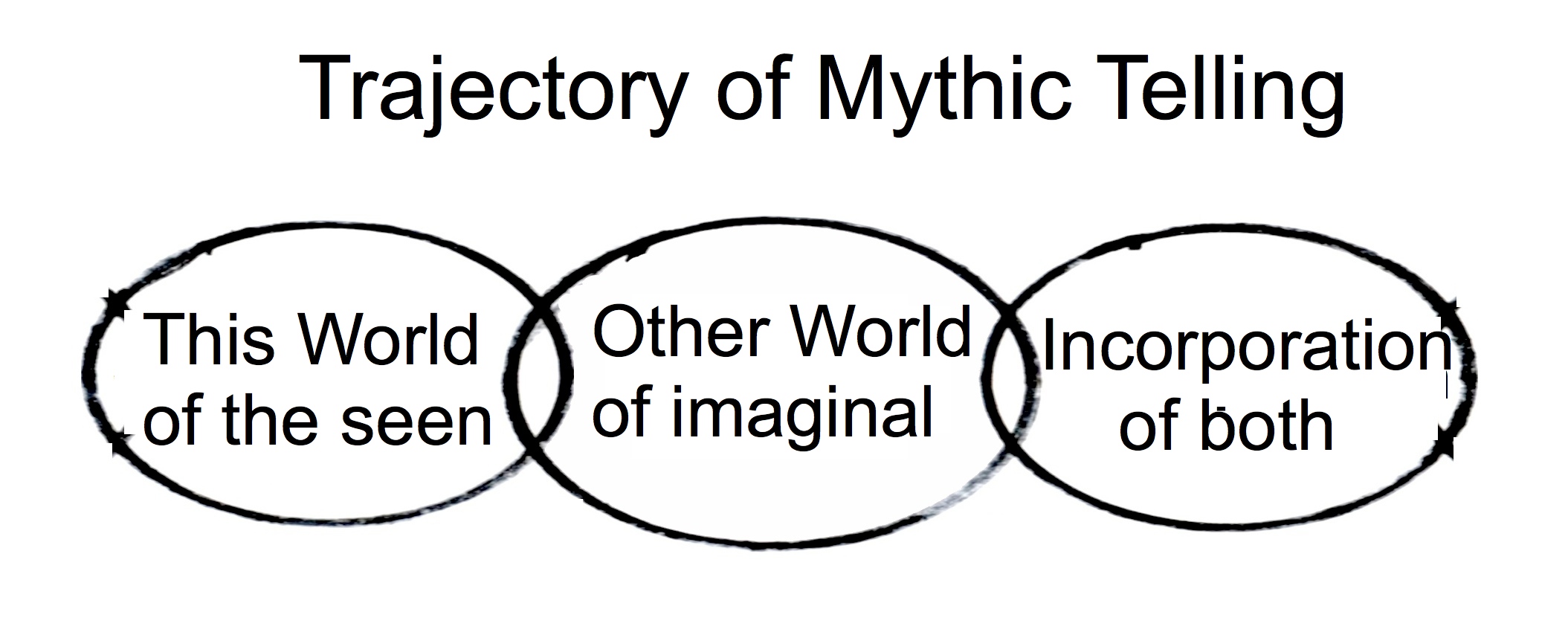

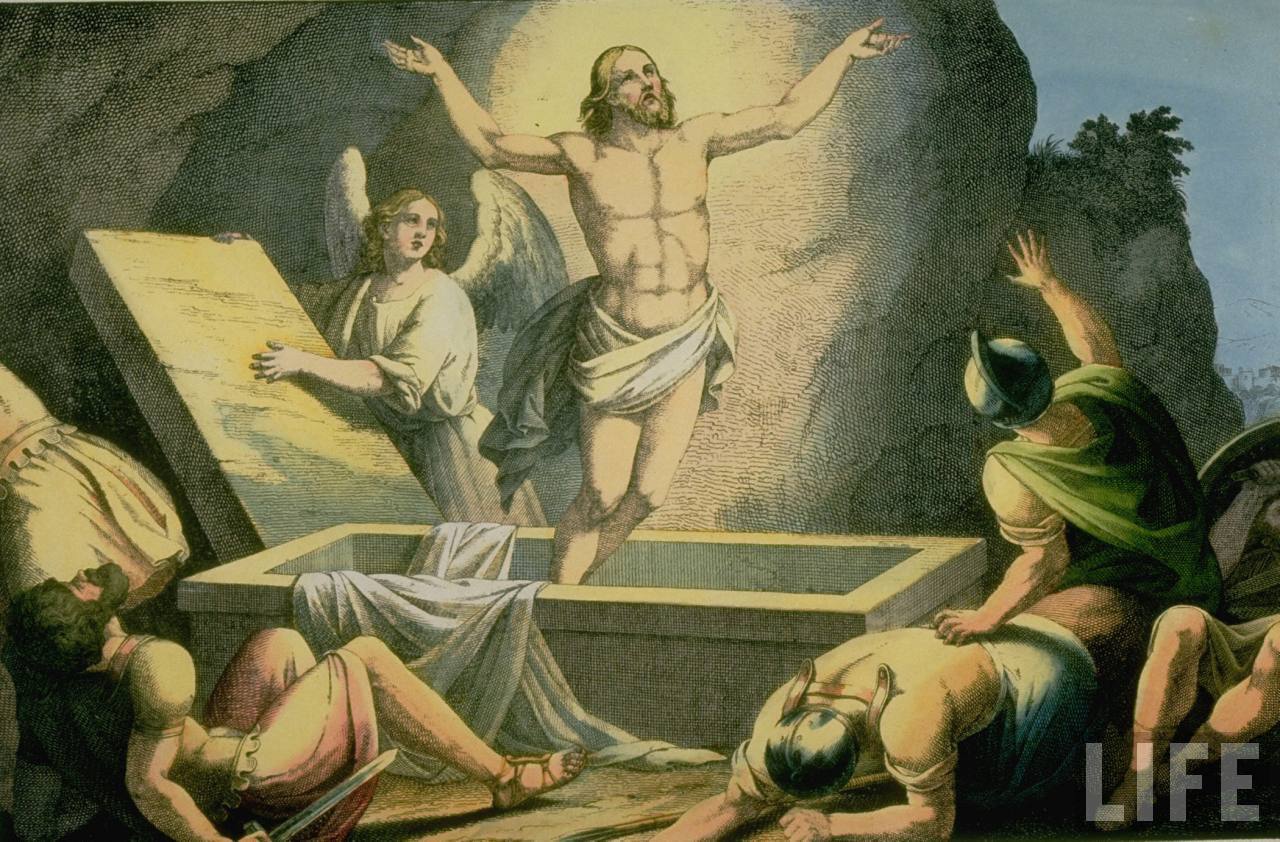

Many attempts have been made in modern times to define myth. It has been described as the "bad science" of primitive humans attempting to explain Nature, the fanciful residue of legends once told about famous historical people, and a disease of language. Modernity's standard for representing reality, founded on the predictable mechanism of physics as the only valid explanation of how things are and happen, has had no basis for regarding myth as representation of reality. Thus archaic myth has remained incomprehensible to a modern mentality. Consequently, the notion of myth has come to mean falsehood, untruth, fantasy, and delusion, But the recent science of complexity and self-organizing system networks provides an entirely new factual basis for understanding what the symbolism of mythical imagination is actually "good for." The most fundamental trait of the images, stories, and concepts generated by mythic imagination across all pre-modern cultures is its concern with magical transformations and the personification of non-human spirits, gods, and goddesses--as spiritual forces that animate all aspects of existence. These are the very traits that make it an illogical fantasy to a physics-based view of cause and effect in Nature. They occur in striking variety from culture to culture over, dating back at least 40,000 thousands years. Clearly this mode of representing self and world were regarded as profoundly important, even essential, to the people who created them. But how could such overtly un-realistic actions, creatures, and ideas have any relationship to the real world we moderns have become so adept at measuring and calculating? Myth as Art If we approach mythic expressions as we tend to do the notion of artistic expression, the mythic can at least be granted the function of prompting an aesthetic experience. Art in our modern context tends to be regarded as having little practical usefulness yet still a valuable part of cultural life. What is called art ranges from a more realistic representational style, in which familiar objects, places, and events are represented much as appear do to our ordinary perception, to completely fanciful or abstract forms, whether as paintings, sculptures, dance movements, movies, or literature. These express a range of events and things, some of which are comprehensible to a mechanistic sense of reality and some of which are confounding to it . Similarly, they can prompt both a pragmatically logical sense of meaning and more illogically emotional experiences that are difficult to explain in relation to the mere objects of matter, color, form, and movement which appear to be the source of such experience. Art in our modern context, as an aesthetic experience, fits into the general category of entertainment. It is something people like to engage for the sake of emotional stimulus, not as information about the actual world we deal with in our daily, practical states of mind. But there are also those who believe Art is something other than entertainment. That it has other functions and purposes. This view suggests that artistic expression, as an experience, somehow provides us with important knowledge. However that might be, there is wide spread agreement that whatever art does, it does so through its production of metaphoric symbolism. The meaning of artistic metaphor is implied by its non-literal modality. In this view, art is imagery, form, movement, and language that is deliberately not a representation of what it appears to be in the terms of ordinary definitions, descriptions, and explanations of things or events. That is, art as metaphor "stands for" something other than what it literally, logically appears to be--even if it represents familiar objects and actions. This implies that there are aspects of reality that can only be effectively revealed by metaphors that communicate by indirect referral, deliberately distorting ordinary definitions by representing one thing as something else. Metaphoric symbolism is a basic element of language. In conveys qualities of things and events that are not readily described in pragmatic, literal terms. We use it on a daily basis without thinking about its logical un-reality when we describe another person as a wolf or speak of raging a storm. Our pervasive use of metaphoric symbolism, not just in art but in everyday speech, indicates it must be essential to us on some level. If we approach the expressions of mythic imagination from this perspective, we can ask a specific question about it. What is its preoccupation with magical action and spiritual animation, as artistic representation, actually about? What is qualities of things is it trying to represent by way of its fanciful, seemingly un-realistic mode of representation? Evidently, whatever that is, it cannot be represented in ordinary, familiarly logical terms--it must not be referring to phenomena that can be described and explained in a practical manner or by the Laws of Physics. Yet there must be some kind of logic about the world, some underlying aspect of reality, that prompts us to employ this type of indirectly implied representation of meaning. Art in general must be concerned with qualities of reality that are in effect invisible to ordinary perception and understanding. We can think of this as qualifying what cannot be quantified or defined in exact terms. Myth as Dynamical Modeling The magical actions, metamorphic transformations, and spiritual actors of the mythic imagination do have something in common. These all involve a way that things happen which is not logical to our ordinary pragmatic sense of reality. It seems that nothing in the literally real world happens in these fantastical ways. That is the very basis of judging myth as un-truth. These fantasies might be entertaining, but they are not practically useful representation of reality. Nonetheless, they can be understood as a way for modeling a type of dynamical activity--all be it one that appears illogical and physically impossible. Viewed this way, mythic expressions convey a sense that events can occur through disproportional, unexplainable dynamics. Further, its spiritual actors or agents suggest there are intentional, even immaterial sources of creativity that somehow influence the forms and events we encounter on a daily basis--as if there exits an other, invisible world behind, or inside, familiar one. This suggests that there is a logic to how things happen, magically and unpredictably yet intentionally, that exists in addition to the familiar, predictably deterministic, mechanistic causality associated with physical science. Paradoxically, mythic imagination seems to be a "vision," a way of seeing hidden dynamics that actually order reality, a way of "seeing" which can only function by representing those dynamics indirectly, as metaphorially symbolic models of how the world happens. The enigmas of myth become intuitions of bi-dynamical ordering:

The New Disorderly Logic of Networks and the Validation of Mytho-Logical Reality

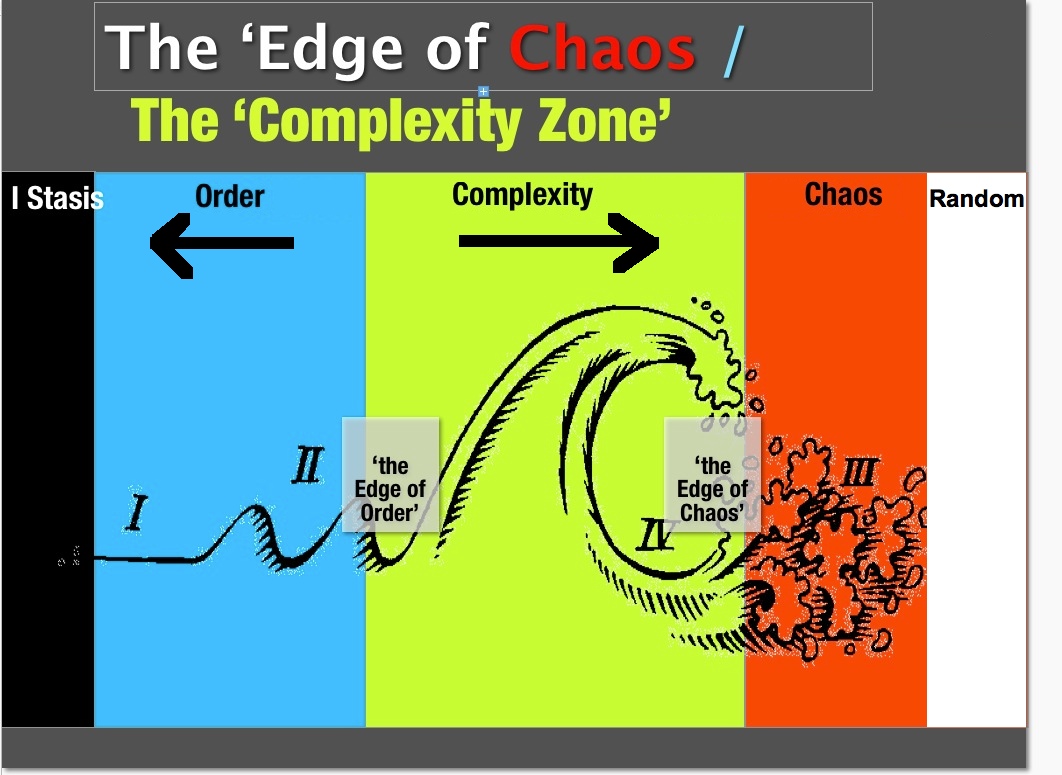

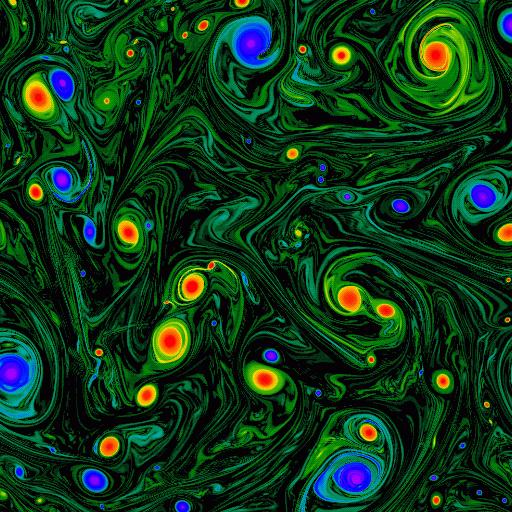

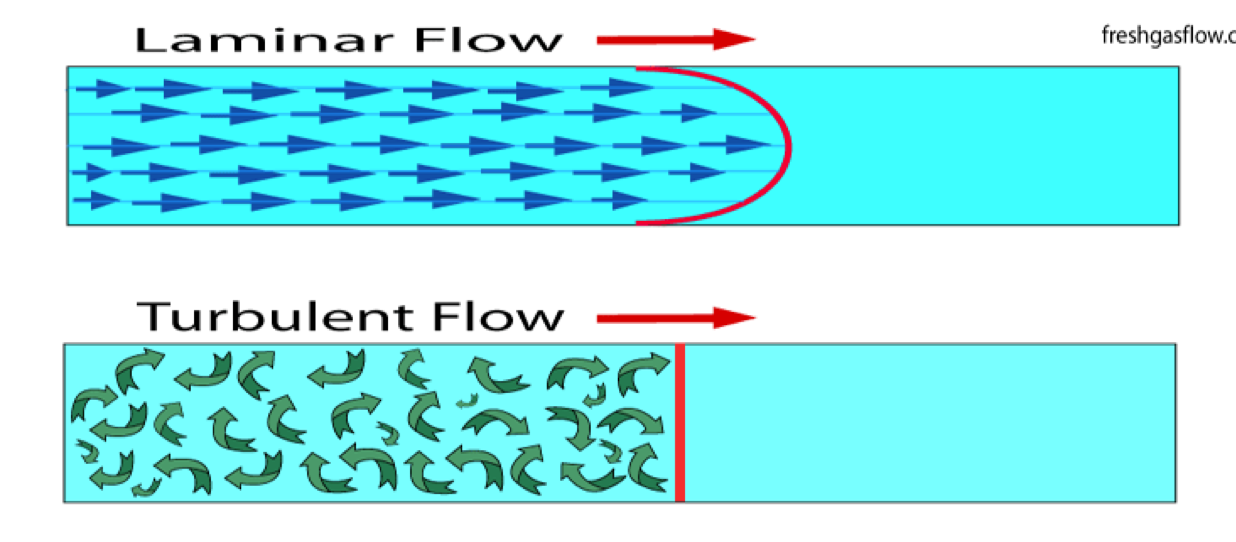

With the above observations about myth as dynamical modeling in mind, when we turn to the evidence and theories of the recent science of dynamical complexity, with its emergent creativity and complex adaptive systems, which generate autonomously self-organizing operational networks, an astonishing correlation appears. The un-realistic dynamics of myth are strikingly similar to the emergent phenomena, whose effects can be quantified the science though their actual process remains obscure. Like myth, this scientific evidence compels us to accept that there are indeed ways that things happen, that the physical worldbecomes into its myriad forms and activites, that are not fully identifiable, explainable, controllable, nor even entirely material. Science and myth have converged as mutually affirming visions of ultimately un-representable dynamics of order creation in reality. Complex systems and network science present a logic of order creation that seems illogical to our modernist sense of causation. In this new scientific knowledge, it becomes evident that the creation of most complex systems in the biosphere derive from disorderly, unpredictably deterministic dynamical conditions: the more complex forms of order, from bodies to economies, necessarily derive from significant disorder. Greater complexity derives from a dynamical condition termed criticality--being a state of partly unstable activity within a system of interdepently interacting parts. This is a dynamical condition said to be "at the edge of chared it cannot sustain its form. If it becomes too ordered, it will not be able to maintain its complexity. The turbulence of activity that approaches chaotic dynamics is required to generate the emergence of network autonomy. On a dynamical spectrum from ordered to disordered dynamical activity,

complexity is a zone between stability at one extreme and un-regulated chaos and randomness at the other.

It is this type of dynamic activity that synergistically allows the actions of diverse, interconnected parts to influence each other, through simultaneous flows of feedback, thereby spontaneously organizing themselves into the entire system. Thus there is a logic to this disproportional, unpredictable, yet not random creation of new, more complex, forms of organization. That is: most organization in the biosphere can factually be shown to derive from this disorderly dynamical condition and cannot be created without it. The ordering of life derives from near chaotic dynamics, not the predictably pre-determining order of physical properties. This proves to be logical because stability and predictably ordering factors do not have the dynamical properties that could create, nor maintain the level of complexity expressed in the living biosphere. But this new scientific story of order creation in Nature gets even more confounding. The source of all this disorderly, disproportional order creation out of systems manifesting criticality includes the emergence of autonomously self-organizing system networks. The critically dynamical activity in the system results in a network of relationships among its interacting parts that "takes on a life of its own" by influencing those relationships. It acts to create, maintain, and even adapt the overall forms and activities of the system. This operational network is not identifiable as the parts of the system nor the quantifiable physical activities of those parts. It is something more, something ethereal, yet something that has physical effects on the system and thus the world beyond it. The two basic terms for these dynamical phenomena are emergence and self-organizing criticality. The self-determining network operations that result, enabling complex systems not only to regulate their forms and activities but to adapt these in response to changes in its environment, are an unpredictable emergent property of self-organizing criticality. It functions in part by somehow processing the feedback flows between the parts into information about the system, and its environment, that enable it so regulate and adapt the overall system. This phenomena is referred to here as network autonomy. That term is meant to indicate how an emergent network expresses volitional action in its moment-to-moment regulation or adaptive re-organization of the system. So the extended logic of complex adaptive network science involves the necessity of this partly ethereal network autonomy for the existence of the complex systems that constitute the biosphere. Without self-organizing criticality and emergent network autonomy there are no life forms, no ecologies, no societies, economies, cities. This new knowledge of order creation mirrors the dynamical modeling of the mythic imagination. The unpredictable creativity of emergence from complexity is the magical action and metamorphic transformation of myth. The partly ethereal operations of network autonomy are the mysteriously creative forces of spirits, gods, and goddesses. In myth, as in network science, there can be no world without these dynamical factors. In myth, as in science, there are "two realms" or order creation, one overtly visible and quantifiable, one not. There is an other, invisible, world behind or within the ordinary world--a realm of spiritually animating autonomous networks. That is what the metaphorical symbolism of the mythic imagination seek to reveal to us. That is the art of myth and the myth-ing of art. The dynamical logic of myth has been confirmed by scientific method. The disorderly ordering of complexity's self-organizing criticality near the edge of chaos is mirrored in the tumult of myth's images, events, and stories. Correlating Complexity and Network Science with the Dynamical Modeling of Myth

If we are willing to consider that science and the mythological method are not inherently opposed, it becomes evident that mythical symbolism is indeed a way of modeling the existence and operations of network autonomy. It was, once upon a time, and still among some surviving tribal cultures, the corollary of complexity science--a useful method for perceiving the invisible realm of emergence and network autonomy. Both share a similarly logical worldview on order creation as deriving from two modalities: the bi-dynamcal one of physic's predictably deterministic but un-intentional ordering and the unpredictably deterministic, partly intentional ordering of emergence and network autonomy. Thus there is sound scientific reason to re-unite science and the mythic imagination in a sense similar to the pre-modern natural philosophers. Only this time scientific methods of quantification and calculation actually frame a factual basis for imagining what that method cannot fully describe and explain. We can generate the doubled vision of a factual imagination to produce a new, non-religious, post-modern metaphysical philosophy. The characterization of myth thus far might lead one to assume it is only concerned with modling emergence and network autonomy. But just as science now must struggle with evidence of a world made by two modes of order creation, so too mythic symbolism serves to establish understanding of the relationships between the ordinary physical world and the "other world" of magical transformations and spiritually animating forces. One cannot be represented, much less comprehended without the other. The Archetypal Dynamism of Science and Myth

Science distinguishes the dynamics of order creation in terms of

sequential mechanism versus concurrently interdependent complexity.

Myth does so in terms of the ordinary actions that can be pragmatically

predicted and controlled, and those that are magically

transformative and spiritually animating.

The corresponding bi-dynamical perspectives of order creation in science and myth: Science Myth > Physics:

predictably deterministic

mechanism

> This World: controllable, pragmatic

events

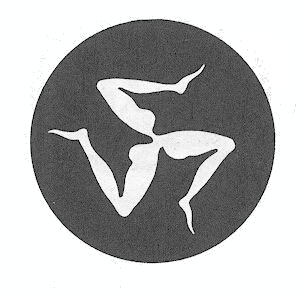

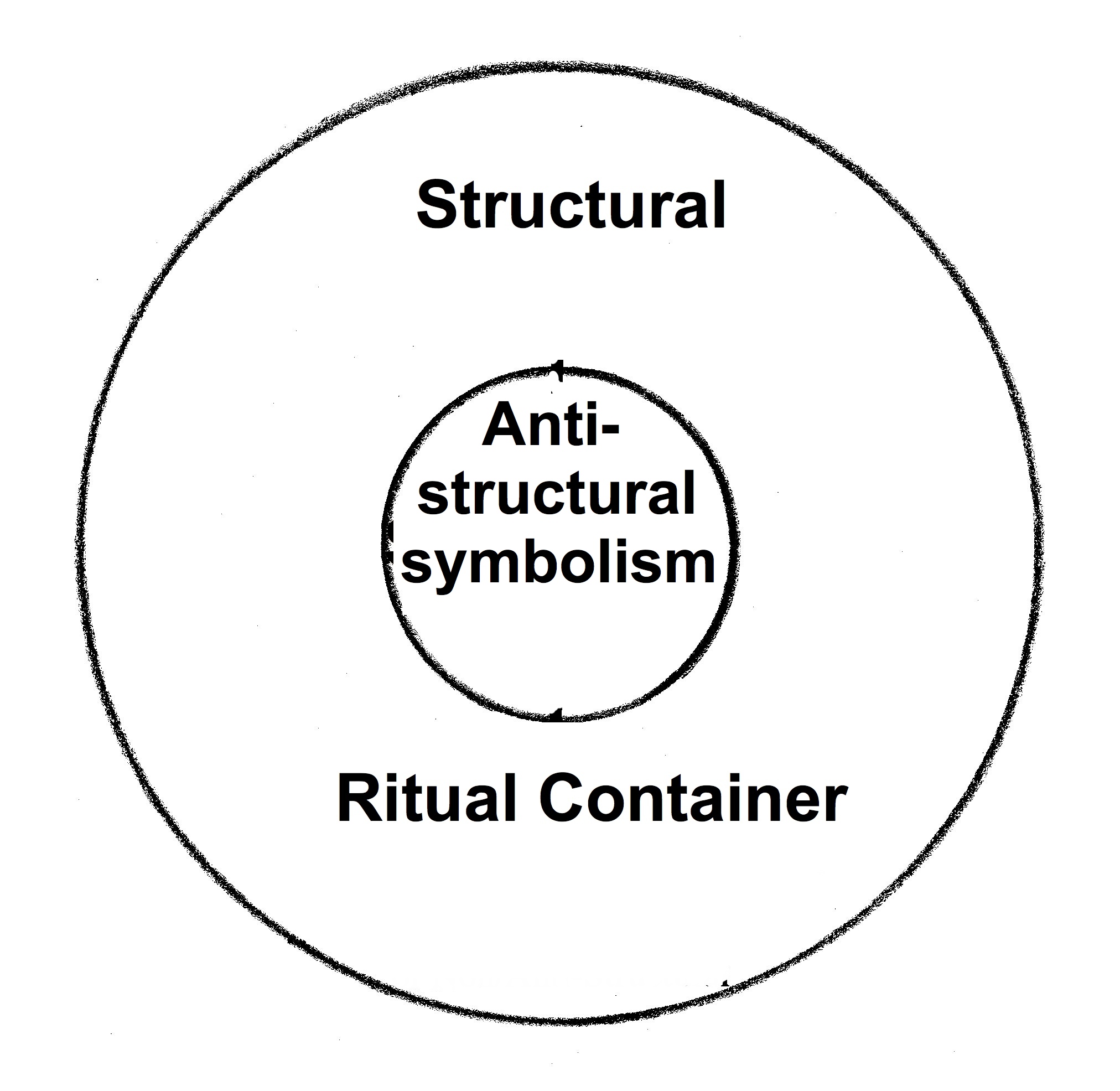

> Complexity: unpredictably deterministic emergence > The Other World: uncontrollable spiritual animation Though science has only recently began to engage the unexpected implications of bi-dynamical order creation, myth is myth because it does so. The difference between science and myth is methodological. Science uses reductive quantification and calculation to analytically differentiate evidence for the two modes of order creation. Mythic imagination qualifies the contrast by characterizing the archetypal traits of complex dynamics using metaphorical symbols. The most overt examples of the tension and coexistence of both modes in mythic symbolism are evident in images that use interdependency of symbolic constellation to suggest the interplay of two or three factors.

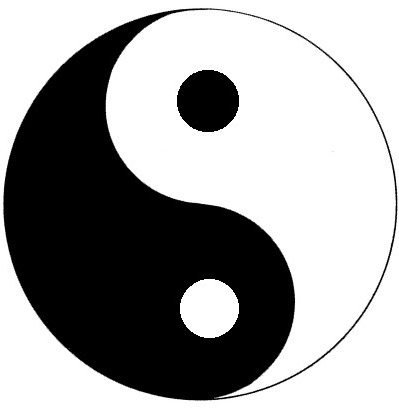

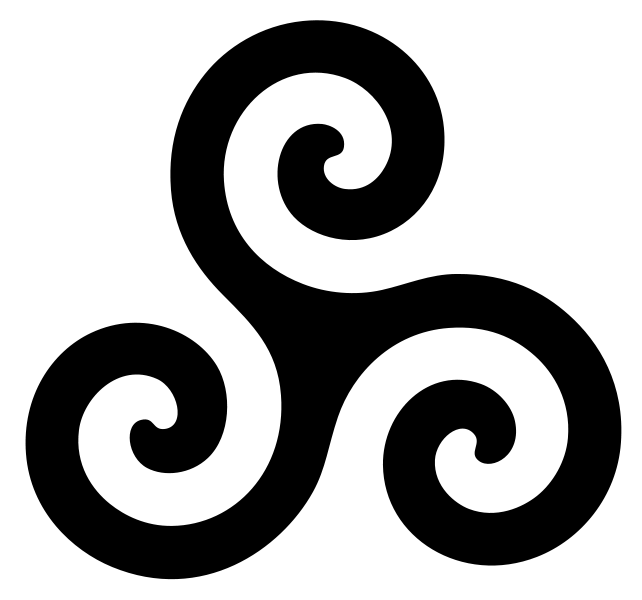

Bi-dynamical symbols

Yin-Yang:

Triskelions:

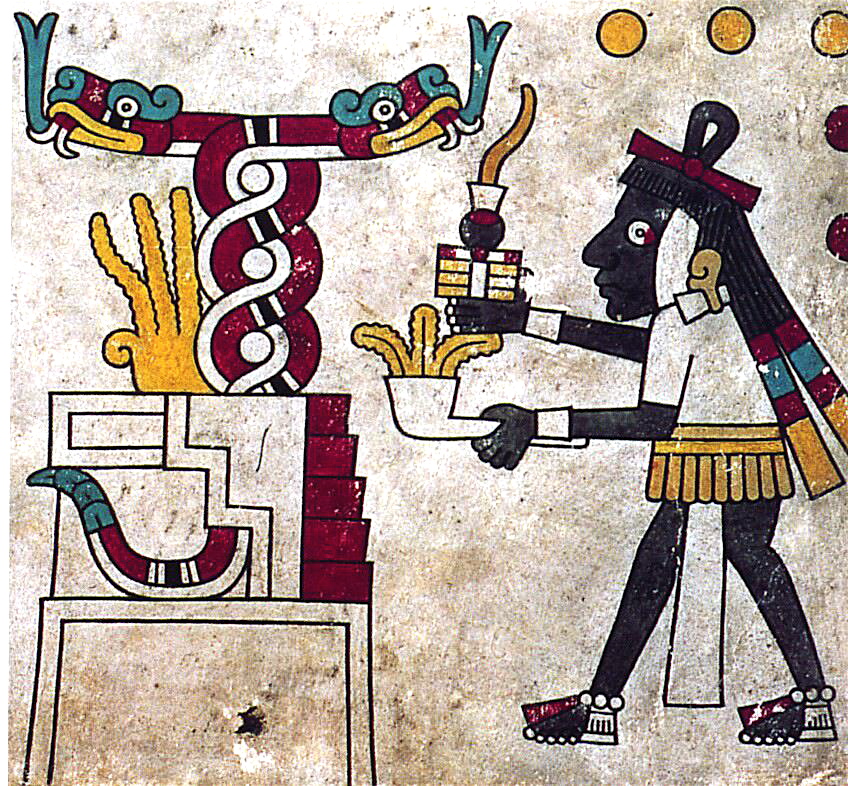

Cadeceus:    These images function to confound our habitual notions of exclusively separate entities acting upon each other the linear progression in events of mechanical causation and order creation. They suggest the quality of dynamical interaction between seemingly separate elements that has no beginning, middle, or end. That gives us a sense of the archetypal character of un-differentiable networked unity. The Yin-Yang can refer to the interplay of masculine and feminine, but indicates these are not exclusive opposites, as each has a dot of the other inside it. Their interdependency is further indicated by the impression of reciprocally moving into each other, in an endless round. Triskelions suggest that there is always a third aspect to phenomena, rather than being configured by simple oppositions or sequences. Where there are two interacting systems there is a third emerging from their interaction as an additional network. The cadeceus is associated with the Greek god Hermes, who is a messenger between the gods and humans. It is also associated with healing, indicating there is more to this phenomenon than a single domain of physical events. Such images prompt an intuition of complexity, interconnectedness, and interdependency--of a non-hierarchical, simultaneous relationship between multiple factors. We can think of these iconic images as archetypal metaphors of the bi-dynamical character of order creation. They remind us to be alert to the pervasive but invisible role of emergence and network autonomy in ourselves and the world. The contrast and co-existence of archetypally mechanical and archetypally complex order creation are illustrated in mythically by notions such as "the other world," which is a metaphor for the ordinarily invisible or hidden domain of complex dynamics. Myth's archetypal other world of complexity is usually "located" as adjacent to that or ordinary ordering--behind, beside, above, below, or even within it. Mythic tales bring the two together by mixing pragmatic acts with magically transformative ones that have the quality of disproportional emergence. The appearance of mythical figures such as spirits and gods provide a sense of the quality of spiritually animating network autonomy. The ways archetypal complexity are described in science and myth can be closely corrleated. The correlations of Complexity Science and Myth

Metamorphism in Science and Myththat constitute the basis for a Scientific Mythology Science: Myth:

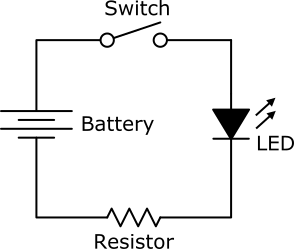

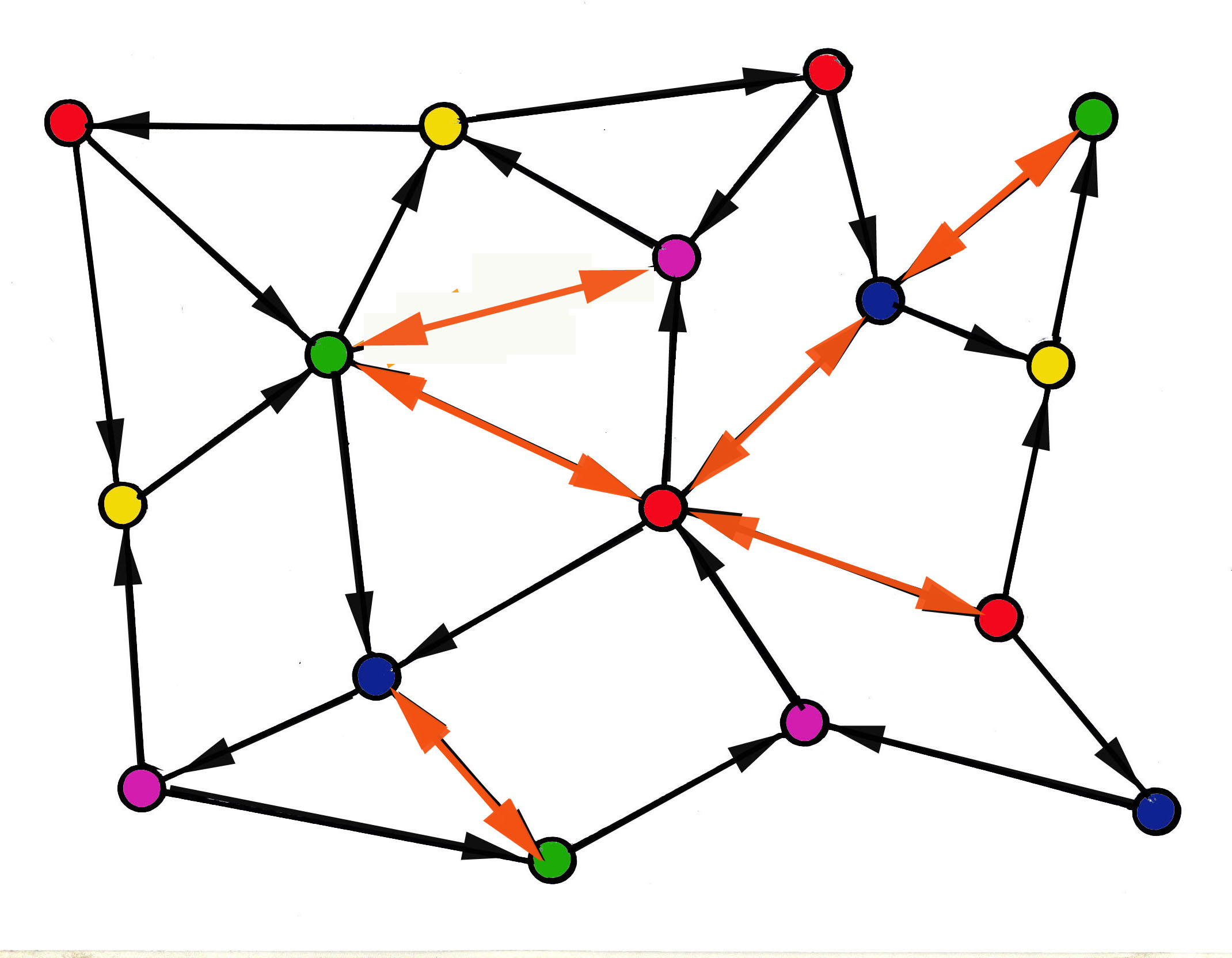

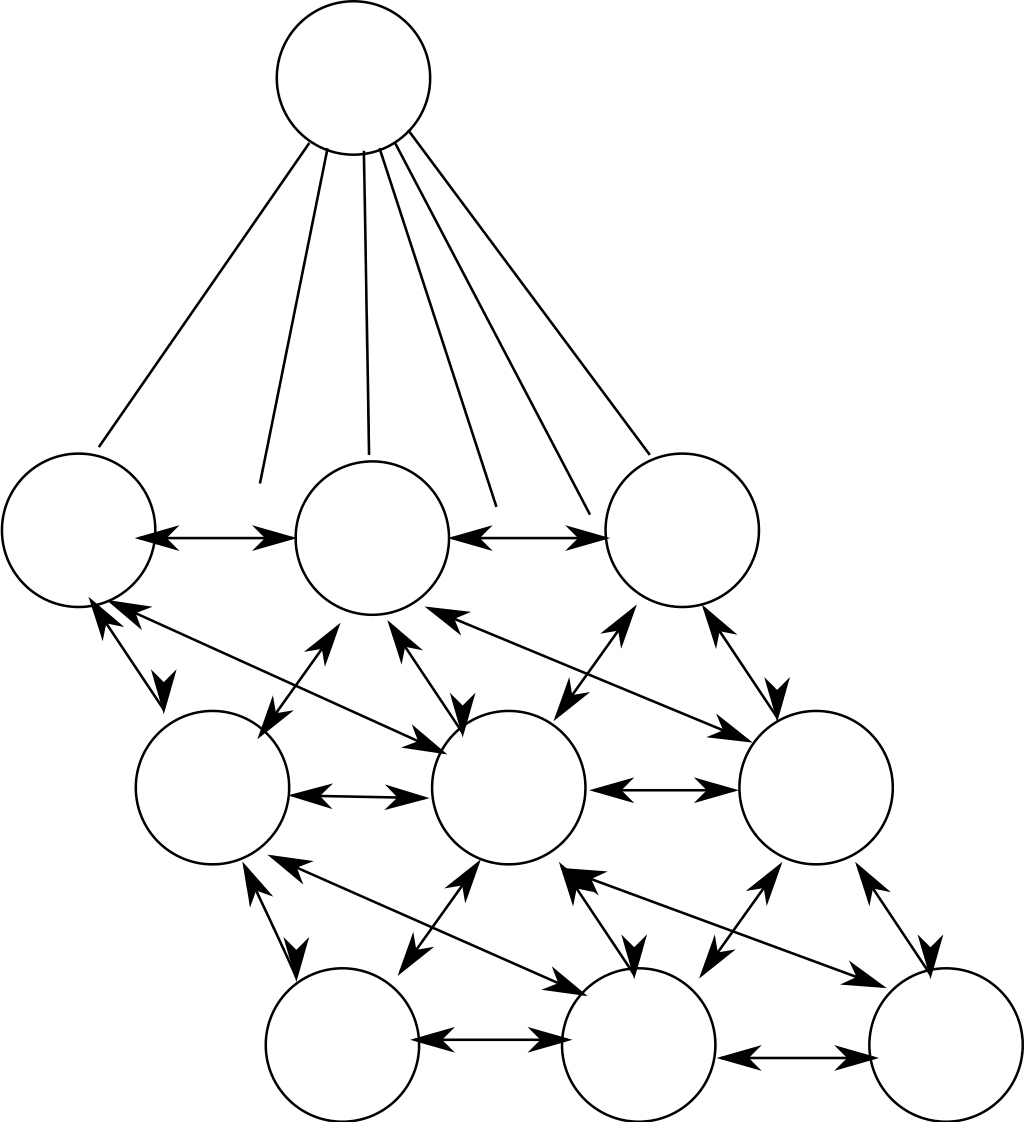

The Mythography as the Iconography of Complexity These correlations show how mythic imagination elaborates the science through its imaginal metaphors of complex dynamics "at work in the world." Engaging these factual and imaginal logics for how things are and happen in tandem provides enhanced perception of the actual ways Nature orders and adapts its interdependent systems. Mythic imagination generates a symbolic iconography of complexity's strange, paradoxical dynamics. It gives images to what the science intimates but cannot fully define or describe. In this regard, mythic symbolism constitutes a mythography of complexity, a graphic imagination of emergent order creation and emergent network autonomy. Yet this association between myth and science offers a way to evaluate our imaginations of how things happen that are "more than mechanistic." The science enables us to evaluate our symbolic iconography for its dynamical accuracy of complex dynamics. To imagine these as being subject to direct, predictable control--human or otherwise--is to contradict the science. An accurate mythography of complexity necessarily appears fantastic to our ordinary perspectives, but not as a fantasy of magical control or supernatural powers of pre-determination. The transformative metamorphosis of emergence in complex dynamics is the change of one form or function into a distinctly different form or function in an unpredictably disproportionate or nonlinear manner. The properties of the changed form or function cannot be found in or logically derived from the preceding status. The properties of form and function in a butterfly are not found in those of the catarpiller from which it metamorphically emerges. Though there is genetic data in the caterpillar to guide the transformation, it is the interdependency of the system's emergent network that actually interprets that data into information as it generates the metamorphosis. The genetic data is a form of memory utilized by the emergent network. Similarly, the transition of a society from a cooperative democracy to an authoritarian tyranny is an unpredictable but not accidental metamorphic effect of emergent network re-self-organization. The transformative effects of emergent order creation provide a way of understanding the realistic function of myth's metamorphic imagery. The magical changes of frogs into handsome princes and the unrealistic confabulations of half-human, half-animal creatures are the metamorphic symbolism of how emergence can radically change the forms and properties of complex systems and their network behaviors. Cultural mythologies generate a kind if "library" of such imagery. They constitute a meta-morphology of the characteristic or archetypal ways emergent order creation transforms things and events in a sudden, unpredictable, and ultimately unexplainable manner. Networks as Characteristic Archetypal Dynamics The contrast between mechanical and complex dynamics is illustrated visually in the schematic diagrams of network science used to represent structural and dynamical relationships. These visualization help distinguish between networks that produce the largely predictable order creation of mechanical dynamics and those which enable the emergence of complexity. The former represents the sequentially dependent archetypal character of mechanistic processes and the latter the concurrently interdependent, constellated archetypal character of emergent order creation. Archetypal

Mechanism

Archetypal Complexity

Network

structure gives us indicators of whether a network will be likely to

generate archetypally complex order creation. In mythic

representation this contrast is qualified in terms of ordinary beings

versus the spiritually animating agents of spirits and gods. When

ordinary humans in mythic tales find themselves in the Other

World of concurrent interdpendency, they notice magical events and

entities that convey the quality of having "dropped into" the

scientific reality of emergence and autonomous network creativity. An

example is the Russian tale of an ordinary human, Vasilisa, who finds

herself in the other world of the magical Baba Yaga. The latter is a

personification of network autonomy in Nature that can perform

extra-ordinary, emergent events. Baba Yaga travels in a flying mortar

and pestle and lives in a house on chicken legs. She gives Vasilisa a

skull that emits light to guide her back to the ordinary world. A basic electrical circuit network: A complex social network:   Ordinary Vasilia with a magical skull lamp Baba Yaga with her house on chicken legs

These two broad archetypal categories of mechanical and complex

dynamics, or ordinary and extra-ordinary ways that things happen, each

have their own diverse archetypal qualities that can be further

elaborated. Science does this with technical definitions of dynamical

activities. Mythic imagination differentiates ways things happen

through different metaphors, created with different constellations of ordinarily

dissimilar things and seemingly unrealistic events.

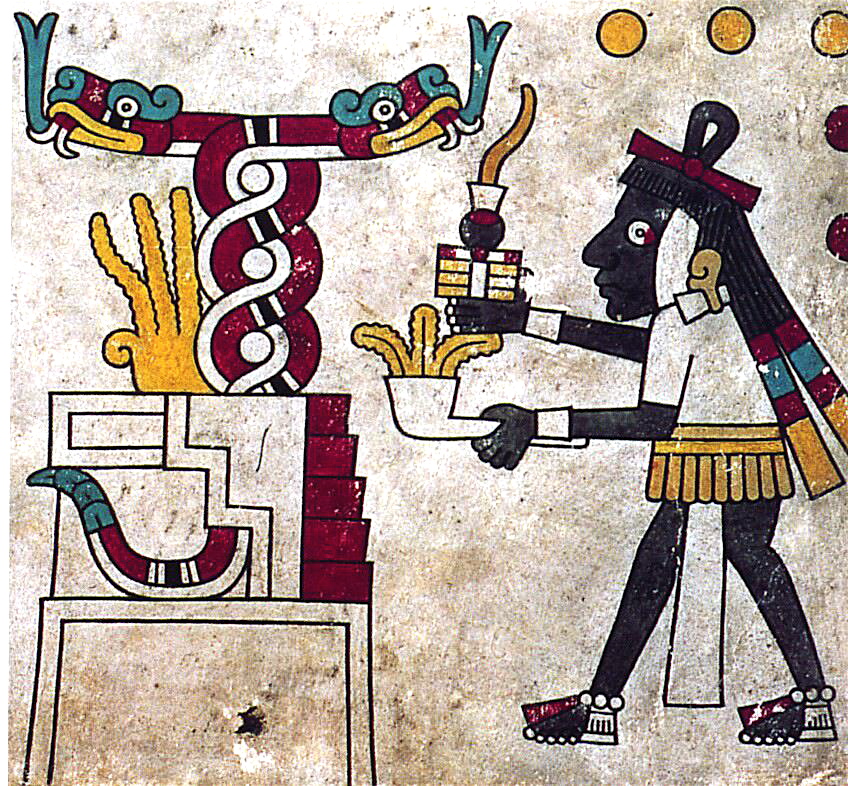

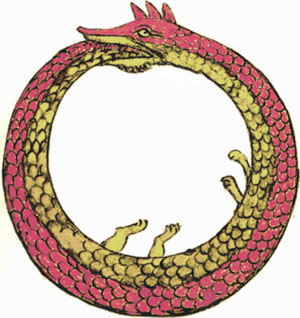

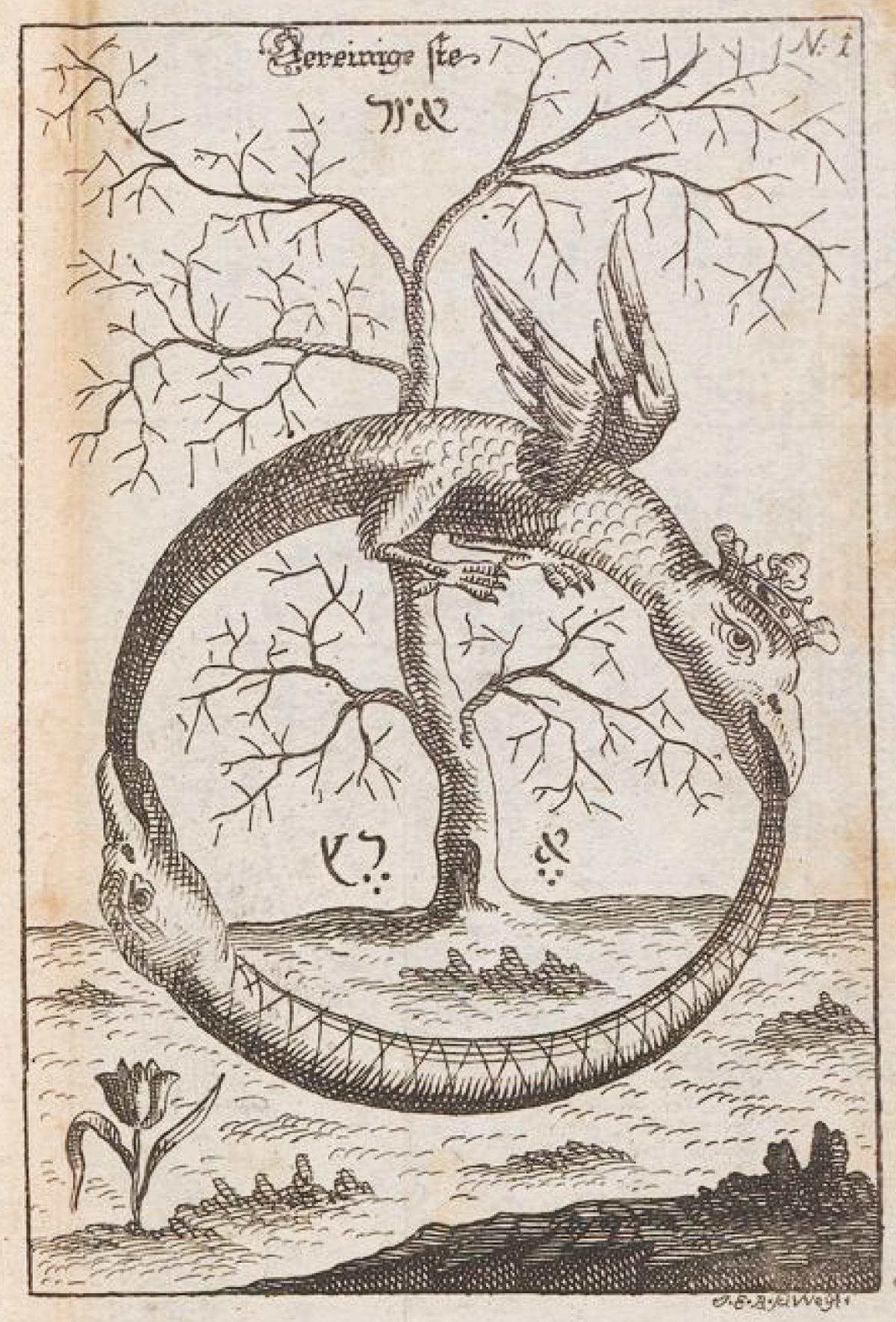

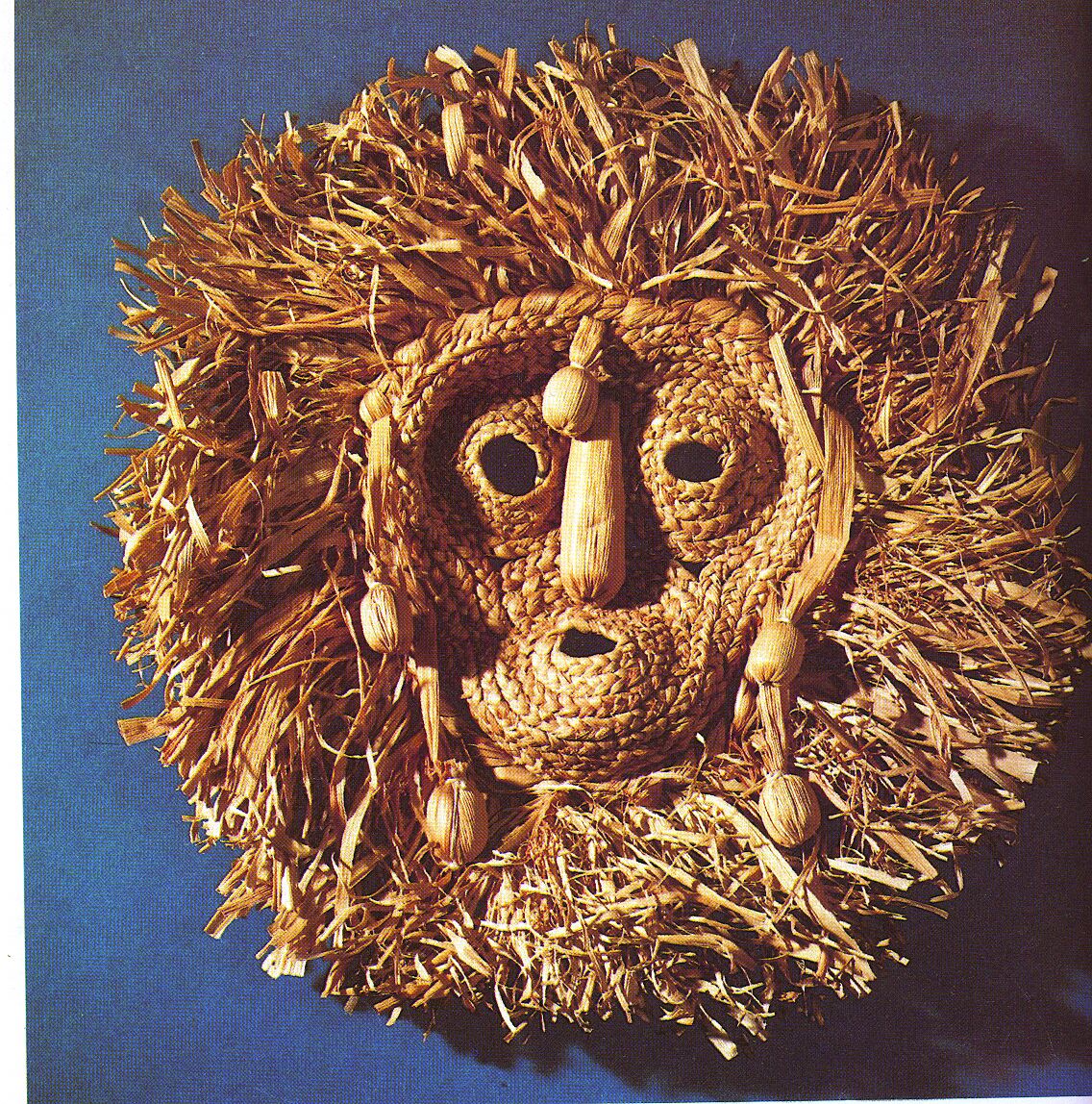

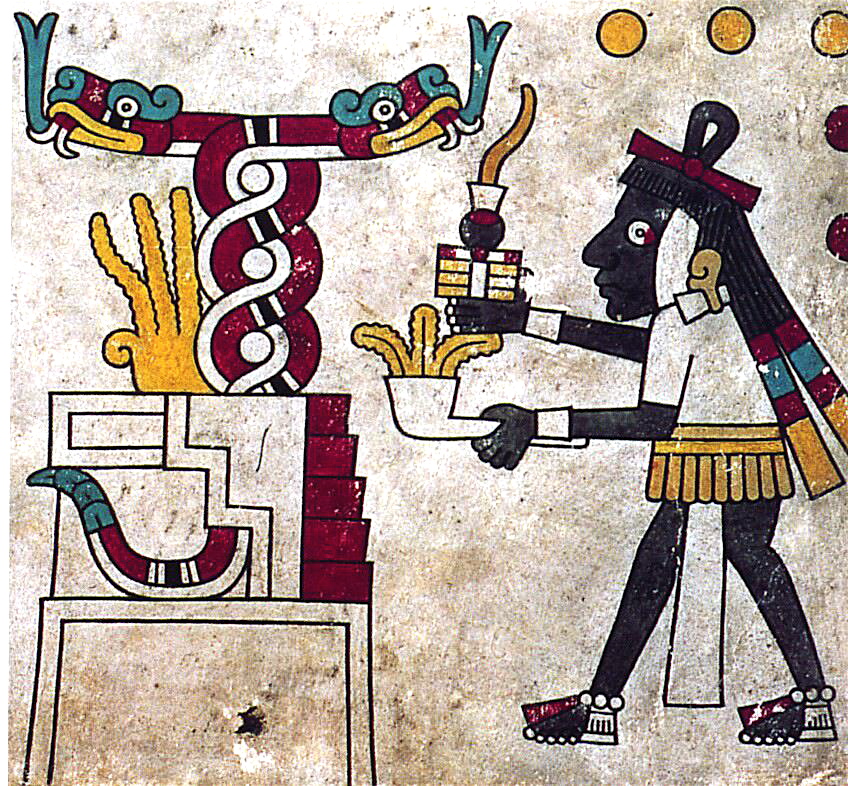

Mythic Symbolism as Archetypal Complexity's Emergent Order and Network Autonomy Archetypalizing Emergence and Netwdork Autonomy: Qualifying what can't be quantified about emergent order creation To archeytpalize is to identify characteristic traits of how something is composed and acts by associating it with qualities of origin, form, thought, and behavior. Adjectives and adverbs are typical word modifiers used to represent archetypal character. In general descriptions, we do this literally with phrases such as "the building creates a glassy, gently wavering reflection." We also use the comparisons of similes like "the crowd flowed like a river," or "his movements were mindless and mechanical," or "he has a wolfish grin." This way of characterizing qualities is extended through the use of more overt metaphors and symbols, such as "the river of the crowd," "he is an automaton," and "he is a wolf in sheep's clothing." Such language use gives us a way of describing our experience of how things are and happen. The emergent events that science cannot fully quantify are qualified in myth by its archetypal symbolism of magical transformation, such as a talking frog suddenly becoming a human prince. Network autonomy is represented by archeyptal characterizing in terms of personality. Mythologizing: Myth-ing the Archeyptal Qualities of Complex Dynamics in Bi-Dynamical Reality Like science, mythic imagination cannot reveal exactly how emergent order creation and network autonomy actually happen. But what the mythic imagination can do that science cannot is re-configure our habitually pragmatic, mechanistic mentality to give us an experience of complexity's extra-ordianry dynamical qualties. Like scientific models of complexity, mythic symbols are a form of abstraction of ordinary reality. They represent things and events in ways that disrupt our habitual perceptions and assumptions about how things are and happen. As stated, artistic expression often does this generally. But mythic imagination can be distinguished as the art of representing emergent order creation, in terms of magical transformation and the network autonomy of spiritual agency or animation. We can call this the mythologizing or myth-ing of reality. It is accomplished by generating archetypal metaphors that have the qualities complexity's nonlinear, emergent dynamics. The origins of imagery suggesting archetypal complexity's interdependency and non-ordinary being are prehistoric. It extends back beyond 30,000 years. There are human-animal figures, associations of the moon and the human feminine, abstract human forms indicating a non-ordinary quality of being and nonlinear activity, as well as indications of interdependent interconnections among animals and human humans.       Mythic imagination represents the traits of complexity's nonlinear dynamics, with their emergent properties of self-organizing criticality at the edge of chaos and resulting network autonomy in a variety of ways. A most basic one involves patterns that emphasize interactive relationships, inter-connectedness, nonlinearity. Greek meander Keltic knot Islamic tile Hindu paisley     These patterns are a way of mythologizing our sense of how things are and happen. They represent a formalized expression of chaotic turbulence that creates recognizable forms in a nonlinear, ongoing manner. Their regularity connects these dynamics with the non-random, self-organizing influence of network autonomy.    Specific symbols are employed to indicate the constellated reciprocal activity, mutuality, interdependence of opposites, and nonlinear directedness of complex dynamics. The European alchemical ouroboros eats its own tale, indicating infinitely reciprocal feedback. The three legs of a Greek triskelion suggests a non-ordinary triplicate, reciprocal movement. The Hindu lingam-yoni combination suggests the intrinsic interplay of masculine and feminine. The double headed Aztec serpent indicates influence that moves in opposing directions simultaneously. Alchemical Oroboros Greek Triskelion Hindu Lingham-Yoni Aztec double head serpent

The creation of small symbols that can be carried appears to be very ancient and extends into preset times. These indicate importance attached to physical representations of non-ordinary states of being and the existence of network autonomy as agency of order creation, or spiritual animation, in the ordinary world. Referred to as fetishes, totems, and talismans, these serve as tangible reminders of the hidden interplay of bi-dynamical order creation in one's self and the world around one. These assist in directing ordinary human awareness toward the invisible dynamics of network autonomy through extra-ordinary mythic symbols of other worldly spiritual animation.

Paleolithic:

Egyptian: Native American:

Hindu:

Greek:

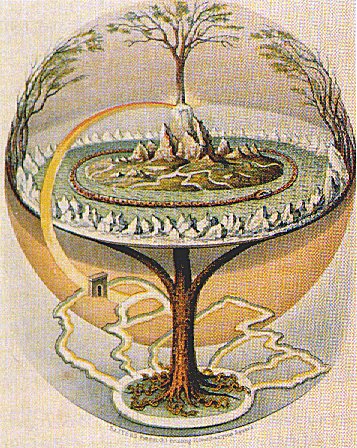

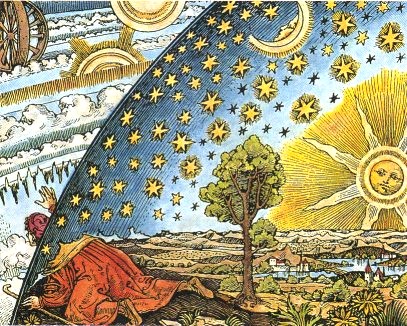

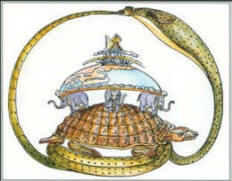

Myth's Other Worldly Models of Bi-Dynamical Order Creation A common theme across cultural mythologies is a notion of an other world that influences the ordinarily obvious one. There are upper and lower realms that act as the source or support for the familiarly visible one. These are metaphors for how the ordinarily visible world is in fact part of a larger meta-system of networks that manifest it through the bi-dynamical modes of dependent and interdependent order creation.    The Disproportional Order Creation of Emergence as Myth's Metamorphic Transformations The magical changes of one thing into another, typical of mythical tales, models the disproportional order creation of complexity's interdependent dynamics. In the other world of myth, these emergent changes are made overtly visible as metamorphic transformations. Ordinary objects are transformed into magical ones, as when a pumpkin becomes a coach in the tale of Cinderella. Humans become animals, animals become human, or are turned to stone, as in the story of the Medusa, and the dead come back to life. Myth is the Archetypal Psychology of how Network Autonomy Animates the World

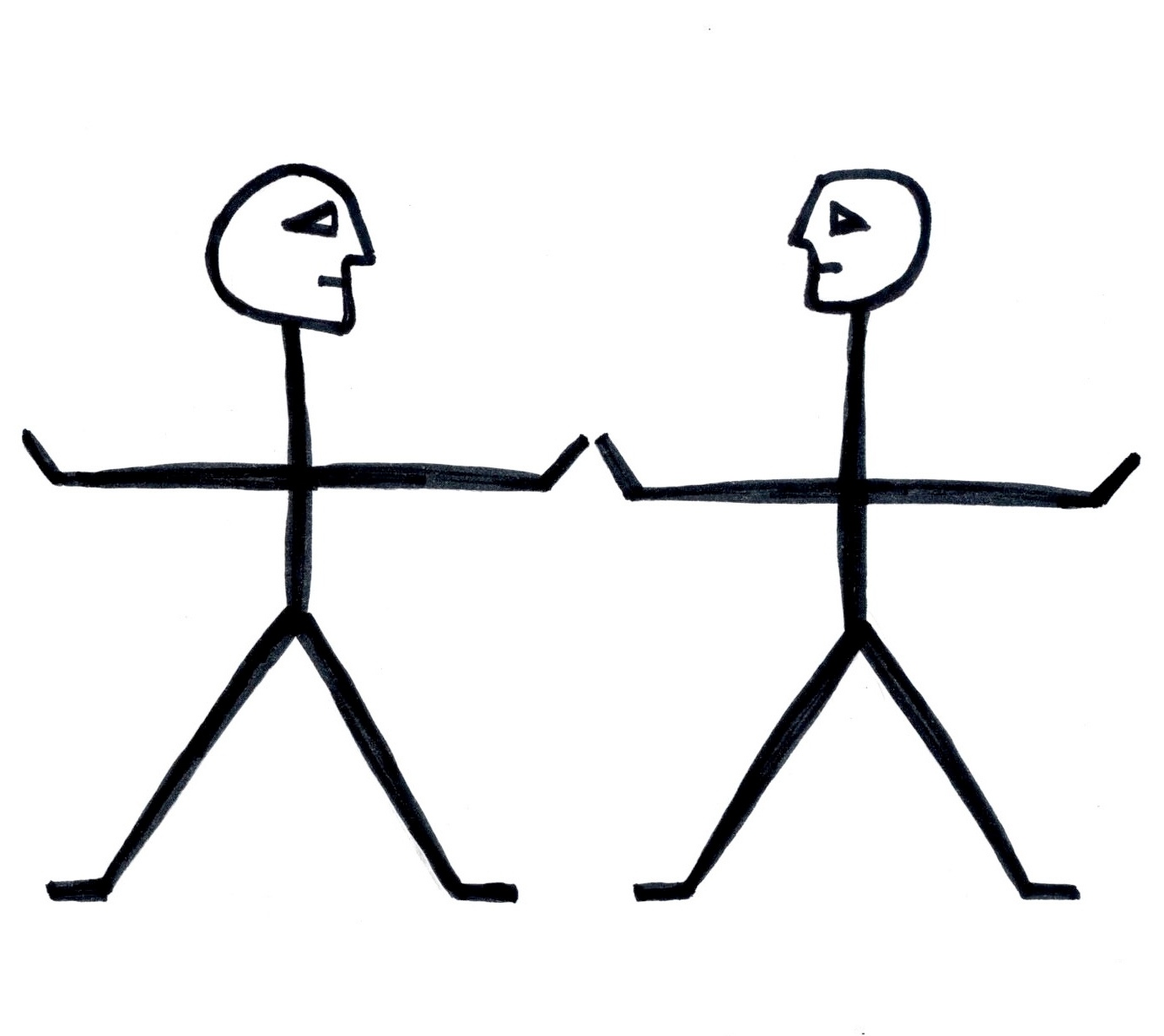

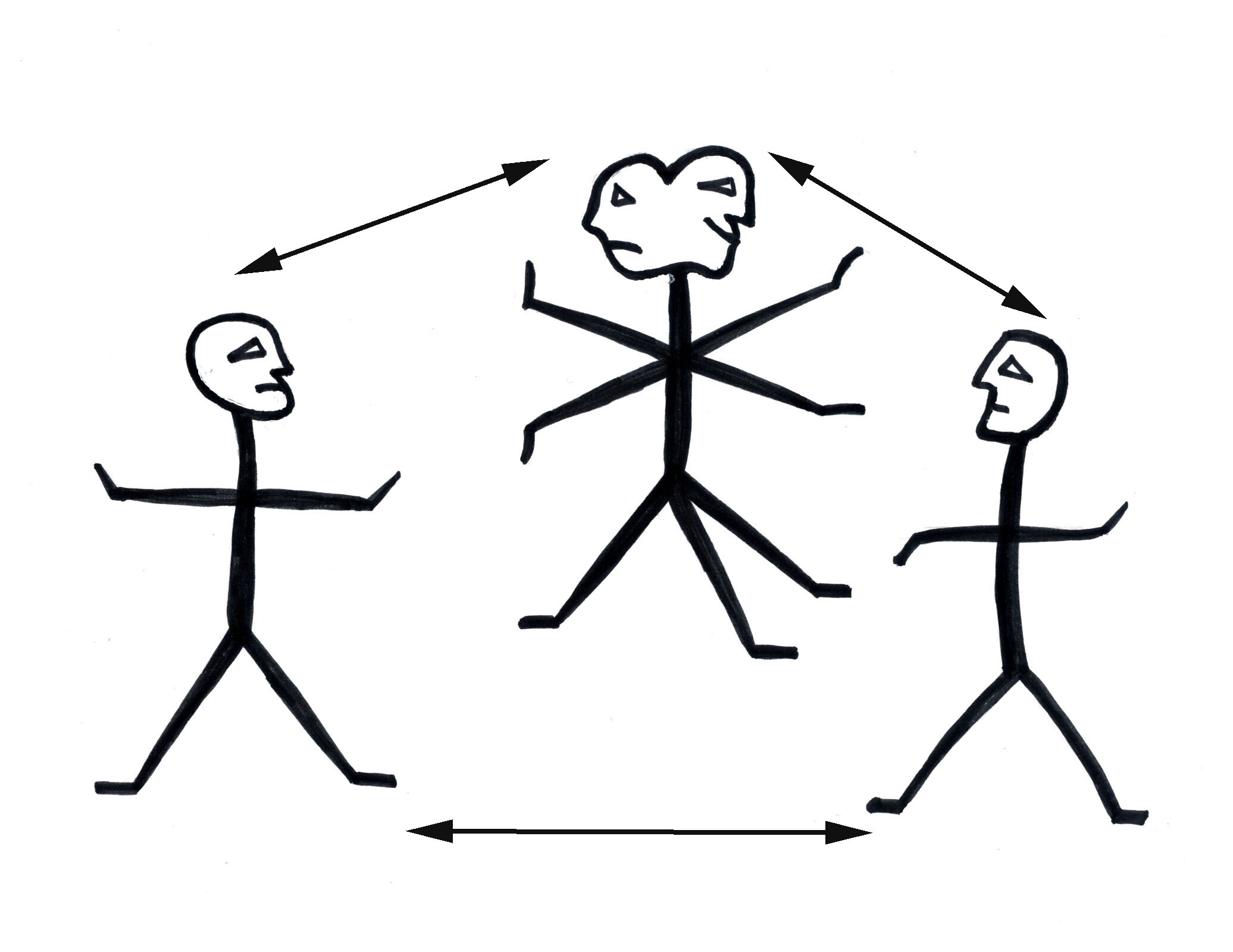

In so far as mythic symbolism is concerned with representing the volitional behavior of complex system's network autonomy, it is necessarily a kind of psychology. More specifically, it can be thought of as network psychology, as a way of representing the behavior character of autonomous networks, thether they operate in/as human or non-human systems.. Symbolizing the Archetypal Character of Network Autonomy Network autonomy's volitional behavior constitutes a form of psychic activity that influences the physical world. Mythic imagination provides a way of identifying its characteristics metaphorically. A common theme is to associate humans with animals as a way of representing their shared behavioral traits.   This creation of composite and metamorphic figures indicates the qualties of emergent networks and their interdependencies. Different metaphors constellate different emergent network character. A man-wolf network has different subjective traits than does a man-horse. In this sense, mythic figures often are best understood as meta-networks of different networks that have become interdependent. There is a kind of principle in both network science and myth that can be stated as: "wherever two interact a third emerges." Yet the three that result from two are also one interconnected network. How mythic imagination might represent the emergent

network of a two person relationship:     Mythic Symbolism and the Psychic Numinosity of Network Animation The term numinosity is used in mythological study to describe human experience of intelligence or mind emanating from even seemingly ordinary things. This is a feeling that events, environments, and things are "creaturely," that they have psychic awareness and intentionality that makes them somehow alive. This numinous aura tends to make people feel perceived even by non-animal entities. As an experience of the psychic quality of network autonomy, numinosity is a general phenomena that has more specific traits depdending on the archetypal character of a particular system and its self-organizing network. A fundamental function of imaginal mythologizing is to promote and enhance this awareness, thereby redirecting our attention to the fact that there is more going on in Nature than what society defines or mechanistic pragmatism can explain. Such awareness is crucial to humans and their societies having any adequate sense of bi-dynamical reality. Emergent Network Ordering and the Psycho-Spiritual Material of Things Just as complexity science reveals how even ordinary physical objects tend to have forms and functions that arise from emergent ordering in complex systems and their autonomous networks, so does mythic imagination represent these as some how magical or spiritually animated. Thus, even the most familiar of things can be experienced as numinous--as in some way a context of psychic or spiritual activity. In the realm of myth, any physical object can become overtly animated by a psychical or spiritual impetus, even to the degree that it speaks or induces the emergent transformations of a metamorphosis. Physical things created by spiritual animation that are, thereby, spiritualized matter:

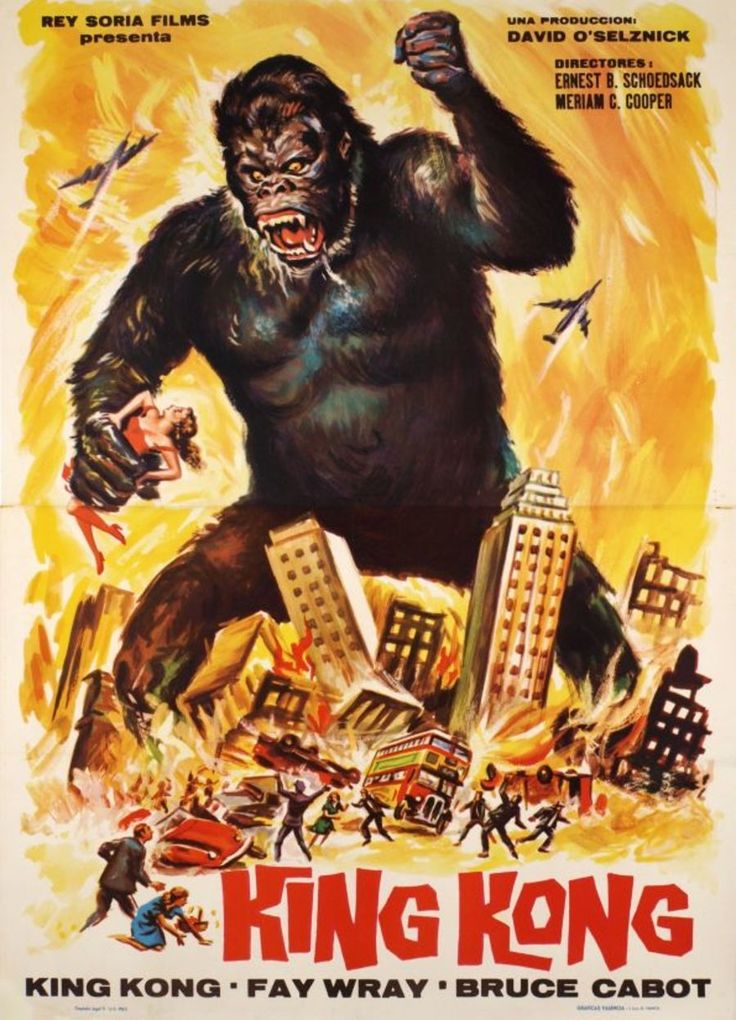

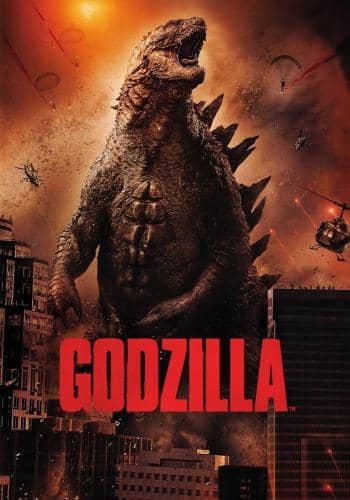

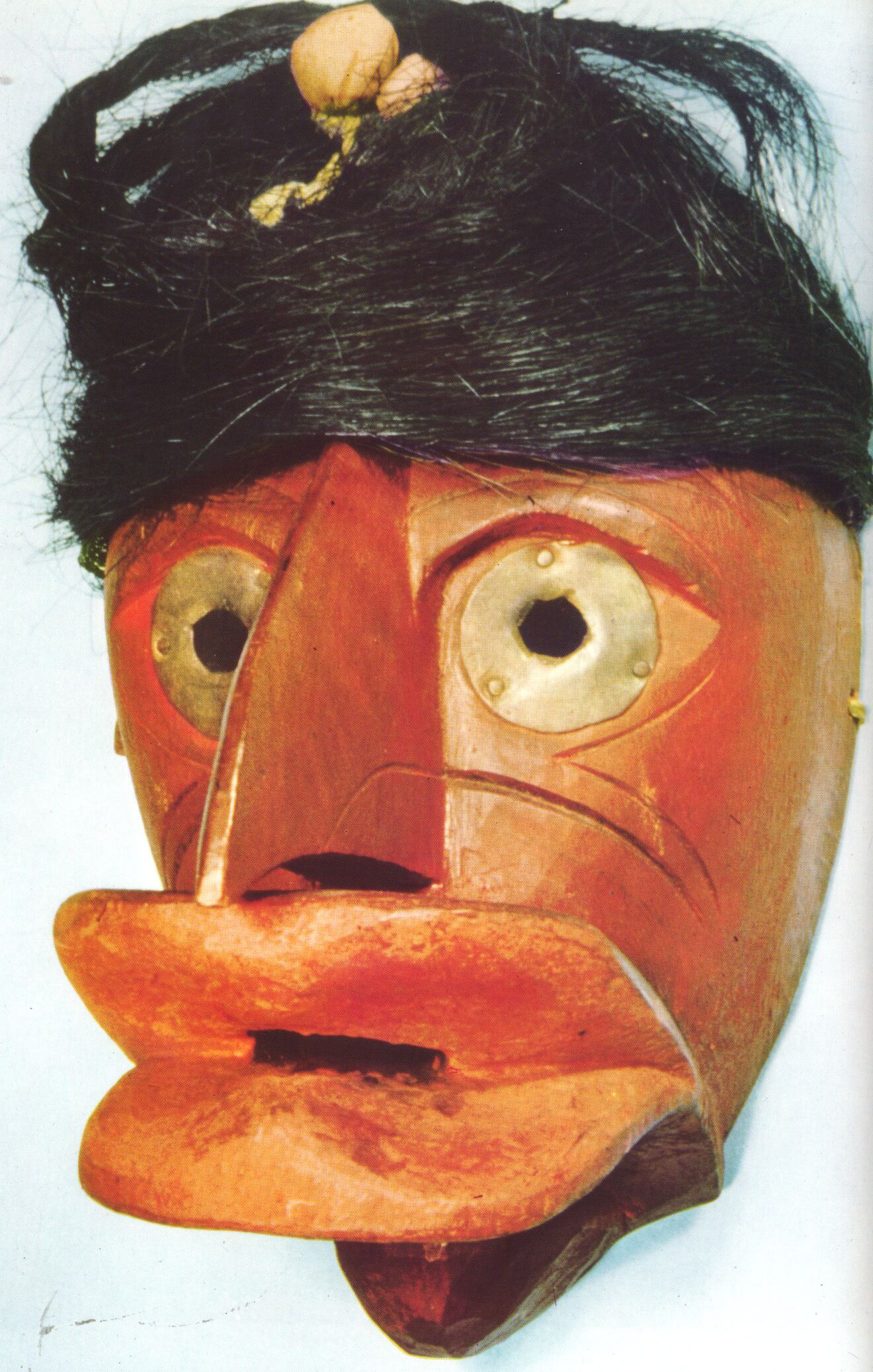

Archetypalizing the Psychological Identities of Spiritual Animators

.

The information processing, willfully adaptive traits of complex

network autonomy is generally archetypalized as psychological

character--giving them the qualities of human consciousness. This personification of the world-animating spirits, gods, and goddesses of mythic imagination are

depicted as diversified, unpredictable, metamorphic, and as likely dangerous as

beneficent for human interests. Accordingly, they are archetypally qualified as

multiple forces with specific characteristic behaviors and areas of influence on emergent order

creation in Nature.

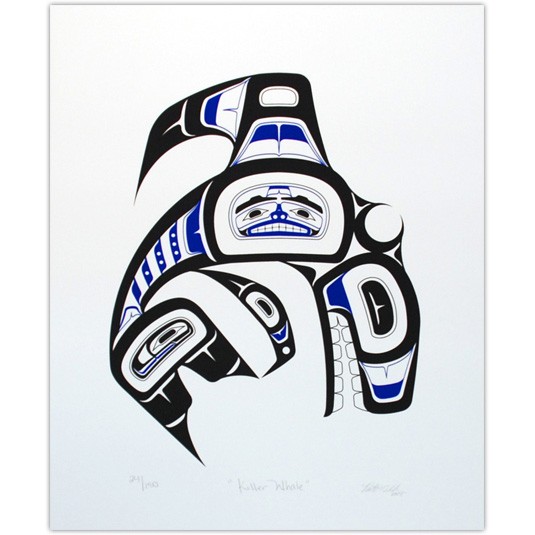

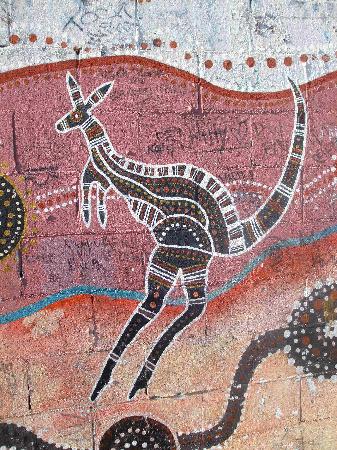

Whether symbolically personified in the form of an animal, human, or more fantastic creature, each is typically individualized as a complex network constellation of diversified, subjectively psychological characteristics. These traits are often associated with the particular power each has for inducing emergent order creation, whether it be concerned with weather or war. They are rarely portrayed as predictably self-consistent stereotypes or as phenomena that can be controlled. However, they are often represented as entities that can be engaged and influenced by each other, as well as by the behaviors of the human network autonomy they influence. To people in mythical cultures, these differentiated forms of extra-ordinary agency are not just abstract concepts. Rather, spirits and divinities are actual phenomena that, though typically invisible to A common posed by modern people is, "Did the ancient Greeks really believe in their crazy gods and goddesses?" Scholars of myth have in essence replied: It was not belief that made the gods real, but direct experience of intentional forces shaping the world and its events. To mythical cultures it appears obvious that something like network autonomy is generating order in the world in a relatively extra-ordinary manner. Traditional mythic tales reveal recurring patterns of interaction between these archetypally qualified animators, and in how human networks are affected by their order-creating impetus. Though unpredictable, there are archetypally identifiable themes in how they act and interact. Thus the world as viewed by myth is an on-going interplay of varied spiritual animators, configuring an ever shifting constellation of relationships and effects. Though unpredictable, this interplay manifests with archetypal tendencies in how it influences both human and non-human systems. Here the scientific notion of dynamical landscapes, composed by differing dynamical attractors, assists in comprehending the meanings of mythic tales. Mythic stories from around the world are configured around recognizable archetypal themes of how spiritual animators behave, interact with each other, and become involved in human relationships. Thus mythic imagination archetypalizes both the diversity of animators and the contexts or situations that they influence. These include life stages such as birth, coming of age, marriage, old age, and death, as well as contexts such as commerce, love, war, and social power struggles. Such context specific archetypal stories constitute a knowledge base that societies can refer to when confronted with particular types of events and conflicts. The Range of Mythical Metaphors for Personifying Network Autonomy's Animating Agency Every cultural mythology represents behavioral patterns of network autonomy in a somewhat unique manner. Symbolic personifications of network animation as spiritual agency range from the very specific character of particular plant and animal species, referred to as animism, to the abstract gods and goddesses of polytheism that represent more abstract archeytpal impetus in emergent order creation. Some cultures favor one or the other mode more, some employ both. Less hierarchically structured societies like tribal cultures often emphasize animism. The more hierarchically structured societies of civilization tend to emphasize the role of "higher" abstract gods and goddesses who have broad influence over generalized aspects of Nature and human society. In this range we can discern a sense of specific system network character, such as an animal species or lake, as well as a generalized archetypal impetus that acts to influence emergent order creation across a range of phenomena, such as a goddess of plants or marriage and family. In the case of monotheistic mythologies, most all of Nature is represented as animated by a single, all powerful, disembodied god character. This diversity of types of spiritual agency reflects the scientific evidence for how network autonomy becomes scaled up as more systems become interdependent with each other, creating meta-systems. The variations between cultures in how spiritual animators are characterized reflects the scientific view of emergence and network operations as ultimately obscure, thus undefinable. What seems to be most important about the symbolic art of a mythical imagination is how its metaphoric representations of archetypal patterning in network autonomy create a means of perceiving and relating to dynamical complexity as a real, if ultimately undefinable, aspect of reality. The variation of how this is done across cultures does seem to reflect aspects of their social order. Civilizations are more overtly concerned with command and control of their societies and environments. So their emphasis upon the abstract powers of higher gods and goddesses seems to express this concern. However, the scientific evidence does provide a basis for both the system-specific characterization of network autonomy and the more abstract form of divine powers that influence these. Where the system-specific animation of particular species identifies archetypal traits of its network's subjective aspects, the abstract divinities provide a way of imagining archetypal tendencies that exist more independently, as types of dynamical attractors that can influence order creation in many types of specific systems. In addition to this distinction between more specific network character that is effectively embodied in a particular system network, versus abstract ones, there are other general categories of mythic animators, such as mythical beasts, monsters, nymphs, daemons, demons, angels, the living dead, etc.. These are useful in symbolizing a variety of ways archetypal impetus can take form in certain contexts of network behavior. The category of mythical monsters, for example, is particularly useful in identifiying network autonomy that causes a system to act in ways that are not reciprocal with other systems and thus become destructive to the sustainability of other systems. Again, none of these can be interpreted as literal descriptions of complex dynamical events. Their function is to provide some means of qualifying conditions that tend to recur in similar if ultimately varied and undefinable ways. Thus the metaphorizing of emergence and network autonomy is necessarily unrealistic in its efforts to characterize archetypal qualities of dynamics that can neither be explicitly defined nor definitively separated, due to their interdependency as interactivity. The most specific embodied animating agency associates more with the terms spirit and soul, usually used in reference to animating personality of human and animal systems, or aspects of natural phenomena like landscapes, wind, and weather. A metamorphic and fanciful category of mythical creatures, such as centaurs, dragons, and monsters also appear as overtly embodied. But the obviously extra-ordinary quality of these figures suggests they represent network agency that takes form and operates somewhat independently of the souls and spirits of individual humans, animals, or features of natural environments. A somewhat more abstract realm of mythical agents that at least appear to have corporeal bodies associate with terms like witch, nymph, elf, dwarf, and fairy. Though often located in natural environments, these are not specifically identified as spirits of those environments, though they may have influence over these. Animating agents that are similarly abstract but less specifically located involve notions of demons, jinns, devils, imps, and angels. These have a more free-roaming quality and seem particularly interested in influencing human behavior. The most abstract type associates with terms like deity, divinity, god, or goddess. Though they are usually identified as human or human-animal appearances, they are also experienced as being present and active as invisible forces. These animating agents who have broader powers of influence over phenomena and often dwell in a specific other world that is located above or below the ordinary one.In general, these animators have the quality of being universal. They can be anywhere and everywhere at once. The Greek Hestia is a goddess of the hearth or home. Thus her influence is present where ever people have created a home environment. Souls and Nature Spirits as Specifically Embodied Network Animation The term soul is most often used to refer to an incorporeal aspect of a person, animal, that generates its individual living character. The term spirit is used similarly but more generally to indicate an incorporeal force that makes a thing alive. Archaic cultures regarded most aspects of Nature to be animated by such an ethereal force. Thus their mythologies are described as primarily animistic. These tend to represent network animation as the personalities emanating from the actual things of the ordinary world--plants, animals, rivers, mountains, etc. This is a more overtly concrete, embodied location of the archetypal impulses of network autonomy. In this way of mythical thinking, there is a distinguishable mode of en-spiriting doing and being associated with particular species. Whales, beavers, and kangaroos can be understood as types of network autonomy that influences the ordinary world in characteristic ways.    Abstracting the Archetypal Character of Network Animation Mythologies described as pantheistic can represent network autonomy as a more general agency that animates Nature without being located in a particular aspect of it. The European Green Man and Greek god Pan are examples. These generalized animators can be regarded as a meta-level networks arising from the interaction of those that are more specifically associated with particular creatures and things.   This meta-level of animating networks expands in polytheistic mythologies to involve a diversified cast of characters constituting what is termed a pantheon. Each has influence over particular types pf phenomena, such as love, war, marriage, healing, commerce, wild nature, civilized society, etc. But their areas of animating influence can overlap and even be contradictory. These animators are more commonly referred to as gods and goddesses, and tend to be personified as more explicitly human-like. They often have on-going relationships with each other and interact in a vast variety of ways. Their behaviors vary depending on the conditions of their "states of mind" and a particular moment in time. They quarrel, love, form alliances in a constantly shifting constellation of interactive relationships. Though often depicted as having human form, their extra-ordinary powers are represented by traits such as multiple arms and heads or metamorphic forms and animal aspects.

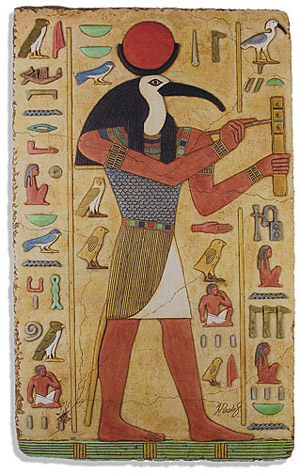

Extra-ordinary appearances of spiritually animating network character:

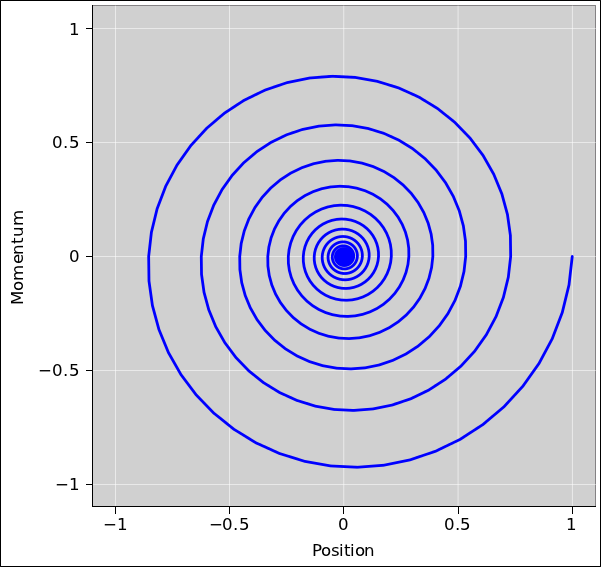

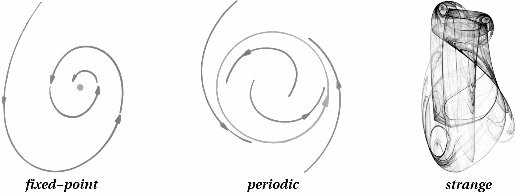

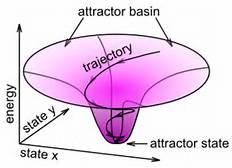

Archetypal Spiritual Animators as Dynamical Attractors

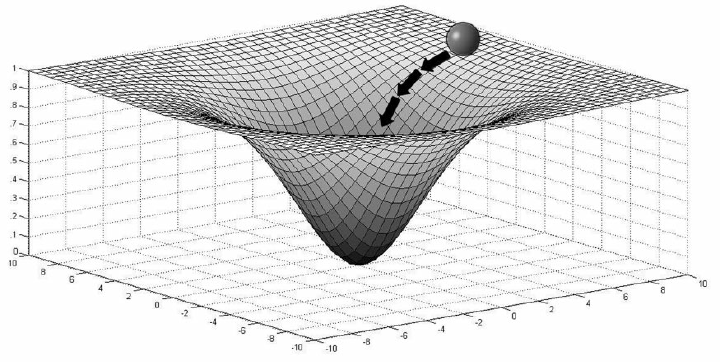

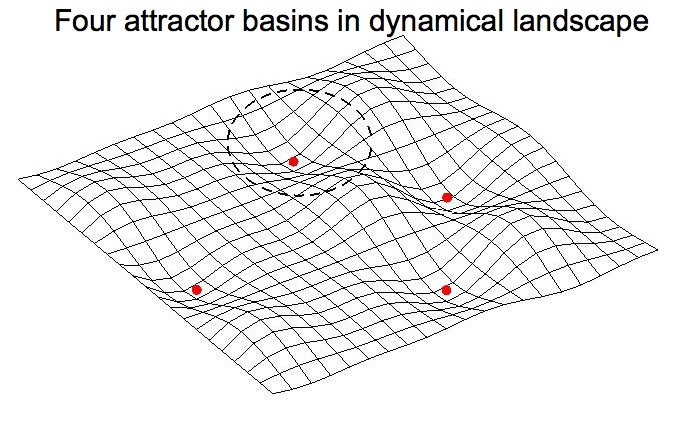

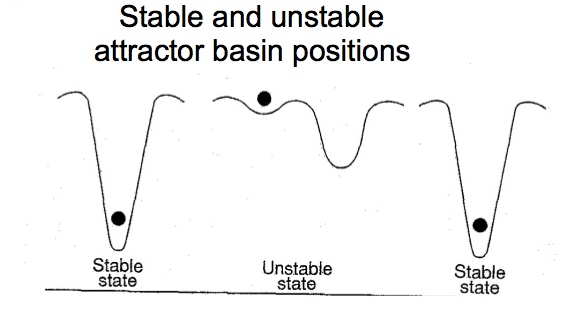

Myth's archetypal characterizations how network autonomy animates the world can be further understood in relation to the scientific concept of dynamical attractors. This concept is illustrated by a whirlpool in water. The actions of the water become a network of dynamic relationships taking the form of a vortex. That form can be understood abstractly as expressing a dynamical attractor. This concept is represented by abstract graphic images derived from mathematical descriptions of the activity. The expression of a dynamical attractor

A whirlpool vortex and its graphic representations:    The spot on the graph around which the motions of the water rotate is called an attractor point. That spot appears as a focal point for the network's active changes in the water. It is the relationships of these changes and the trajectory they trace over time and space that constitute the network's formation of the of water molecules into an the order of an identifiable system. Though this point appears as central to the activity, this it in fact exerts no force upon the water directly. It is a mathematically calculated expression of the network's dynamic behavior. So the attractor is not a physical thing but an expression of the interactions of water molecules as the system self-organizes into patterns during chaotic turbulent flow. Simple mechanical systems, like swinging pendulums, express what are termed fixed point or periodic attractors. These attractor expressions are the mostly predictable and thus readily calculated. They can be graphed in two dimensions. But systems with the more unpredictable behaviors of chaotic and complex dynamics produce patterns so irregular and convoluted they are best graphed as three-dimensional forms. These 3D graphs express multiple or moving attractors points, termed "strange attractors" in reference to the instability involved in a system's creation of its organization. Dynamical attractor expressions--predictable and strangely unpredictable

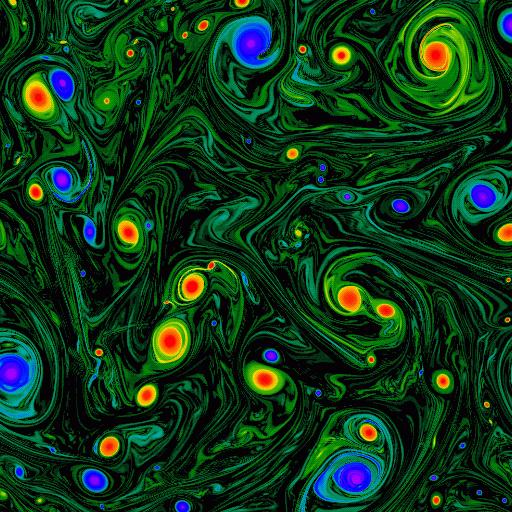

Examples of the 2D patterns of predictable fixed-point and periodic attractors and the more convoluted 3D formations of strange attractors:  Graphs showing strange attractors can reveal multiple attractor points, between which system activity oscillates in a never exaclty repeating but still identifiable pattern of self-organization. The complexity of the various loops and spirals on these graphs indicate the expression of multiple attractors manifesting from the interdependent interactions of system parts. Strange attractors

Dynamical maps of complex system behaviors:   As complex as these graphs appear, they do give us the impression that they chart courses of sequential trajectories, as if a system's activity were progressing around attractor points in a simple 1, 2, 3, progression. But the graphs chart the trajectory of the entire system, relative to its past actions as plotted on the graph axes, not all the events within it at each position on the graph. Even in the case of simple, dynamically linear mechanical systems, many actions can be occurring simultaneously. In chaotic and complex systems, with their non-linear dynamics, there can be vast numbers of actions and interactions occurring and modifying each other in each instant of time--resulting in their unpredictably emergent order formation. Thus one must imagine the lines on the graph as representing continual interactions and organization emerging out of disorderly conditions. Such images give us an impression of the interplay of contrasting and conflicting impetus in how a system's operational network is emergently generating its forms and operations. They visualize the disorderly ordering of complex networks. We can think of these forms as the "finger prints" of a system's network autonomy, through which it generates the similar but never exactly repeating behavior of its particular animating character or network soul. They are, however, blurry finger prints, relative to all the relationships of interactivity occurring concurrently moment to moment. Spiritually Animating Agency as Dynamical Attractor Expession The dynamical portraits of strange attractors presented by these graphs have a striking visual resonance to mythical imagery. Many mythic symbols suggest interaction and trajectories that occur around a central point or axis. But the configurations of these patterns tend not to direct attention to those central points as the source of the actions. Instead, central aspects often more as expressions of the motions implied. The movements and their related trajectories generate the appearance of a center that is like the expression of one or more attractor points.      Even the simplest seeming mythic images, like crosses or circles, suggest that a center exists only as an effect of the interactions of lines which indicate directional orientation or movement. The most basic dynamical symbols

Intersection, interior, and division as expressions of directional dynamics:    Similarly, mythic images of spiritual animators themselves often indicate their character expresses a plurality of dynamical agency, rather than a singularity. Spirits of dynamical complexity

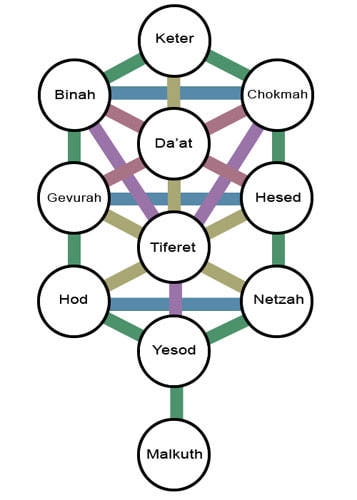

Twin serpent Aztec god: Many armed & headed Hindu god: Three-faced trinitarian Christ:    In various ways, these figures "put a face" on dynamic complexity in a manner similar to how graphs give an impression system behavior. Thus, as metaphoric personifications of network autonomy, they can readily be understood as the expressions of strange dynamical attractors--as symbols of the interactive character of emergent network behavior. Their diversity indicates the archetypal range of how this order creation manifests in Nature. Their contexting as other worldly, typically eternal spirits, which can be anywhere or everywhere at once, shows that such expressions of ordering exist as abstract, immaterial patterns. In other words, where ever strange dynamical attractors are manifested, there too are the spiritual animators of myth. A further resonance between myth and the science of dynamical attractors is evident in how a multiplicity of spiritual factors gets represented in non-hierarchically networked relationships, suggesting the interactive dynamics that are mathematically graphed to reveal the expressions of strange attractors. Network orientations in spiritual traditions

Hebrew Kabbalah: Australian Aboriginal

ancestor spirits: Taoist I Ching elements of Nature:   In conclusion, then, the convoluted three-dimensional graphs of strange attractors and mythic symbols both serve to represent the emergent order creation of concurrent interactivity of complex network dynamics. Both give us impressions of how such networks operate, with self-organizing intention, to create, maintain, or modify their forms--thereby animating the world. Thereby, they assist in our perceiving that the things of objects and events are not simply "made of" matter and energy, but the creations of ultimately invisible, undefinable, centerless network relationships--relationships, however, that express at least some identifiable archetypal traits. The Mythical Fields of Dynamical Attractor Landscapes A counterpoint concept to that of an attractor is an attractor basin. A basin is represented graphically as the outer boundaries of the shape created by the trajectory of a system's dynamic changes as it moves toward organization around an attractor point, or points. Though a basin looks like a physical thing that is forcing the system trajectory into a pattern "from the outside," it is actually a mathematical description of the relative actions of a system over time, which is used to generate an abstract visualization of the boundaries of a system's trajectory toward an attractor point. When that trajectory reaches a point of relative consistency in system behavior, it is considered to in an attractor state. Visualizing attractors as external forms

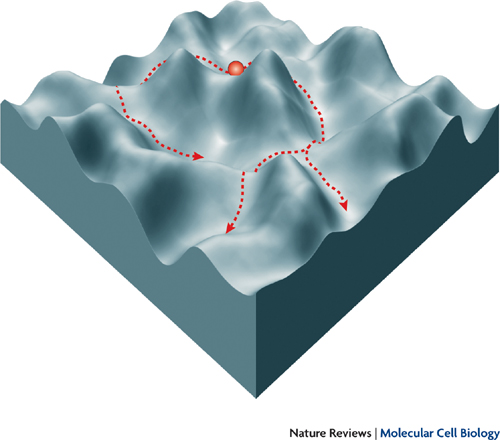

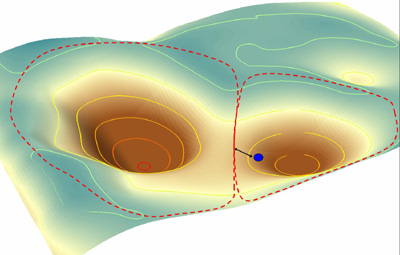

The basic 3D representation of an attractor basin:   Though the basin graphs give the impression of a physical form that is being that is "pushing" a system into a shape, like a literal ball rolling into a funnel, and attractor graphs suggest that certain points in space are "pulling" the system into an order around them, these impressions are misleading. The active 'forces' that are giving the system these configurations arise from interactions among system parts, and between these and other factors in the system's external environment. A physical system that provides a tangible example is a tornado. Its vortex takes initial form from the flows of heated air rising into the atmosphere under conditions that promote an spiraling currents. The system of the tornado emerges within the conditions of an external environment, as an array of chaotically interacting dynamic activities. These then self-organize into its operational network, which in turn interacts with its external environment. What can be calculated as the tornado's attractor basin, trajectory, and attractor point/s are expressions of these interdependent interactions. However, such emergence of form and operations from dynamical events are not limited to completely physical phenomena like tornadoes. They occur in a similar manner in the complex systems of ecologies, economies, and human social groups, where feedback among system parts involves the interpretation of physical data into meaningful information by autonomous networks. These systems also express attractor basins, points, and states. But these cannot be specified like the physical properties of a tornado. Thus, the scientific visualization of dynamical attractors and attractor basins can produce representations of how order takes shape in ways which involve more than explicit physical forces. Dynamical attractors and basins can represent the appearance of directing, constraining forces which have order creating effects but are not literal things. Comparing the ways these manifest from various systems reveals similar tendencies that suggest there are archetypal traits to how system networks behave. Chaotic systems express attractor traits distinguishable from those of complex adaptive systems. In this regard, dynamical attractors "stand for" various ways the order is generated. Though derived from mathematical calculation, attractors are not physical things or forces but representations that characterize modes of emergent, self-organizing network dynamics. In this regard, they are like the spirits, gods, and goddesses of mythic imagination. Just as different types of attractors characterize archetypal traits of order formation, so do the individualized metaphors of spirits and divinities. Thus the spiritual imagination can be viewed as visualizing characteristics of autonomous network behavior in complex systems by personifying these as types of dynamical attractors. These figures, like the dynamical attractors of science, are not literal things that "push and pull" order into being, but representations of the archetypal character traits of emergent order creation. The concepts of dynamical attractors and basis are combined into that of attractor landscapes. These are visualizations of topologies formed by multiple attractor basins. Images of attractor landscapes enable us to image the effects of adjacent attractor basins and the points toward which system trajectories tend when moving into one pattern of behavior versus another. Here again, though this idea can be illustrated by literal physical landscapes, like hills and valleys that direct the flow of rivers, it applies to the ethereal aspects of emergent network autonomy as well. Visualizing multiple attractor manifestations

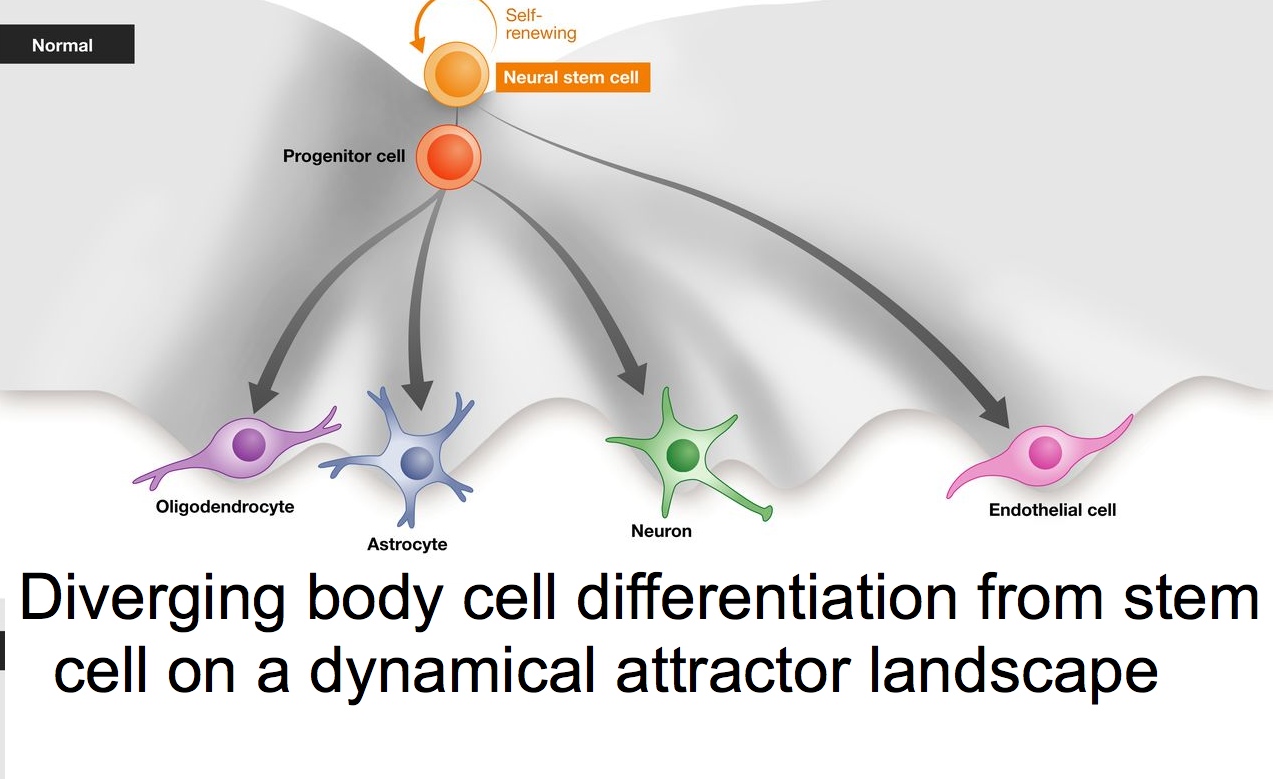

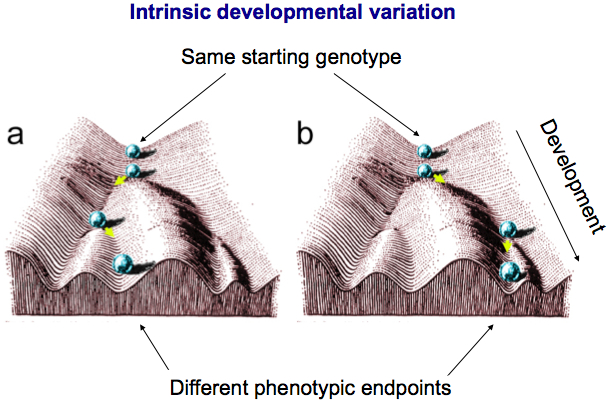

Graphic representations of dynamical attractor landscapes:    Like water flowing into a whirlpool, things and systems can be in stable or unstable positions on an attractor landscape. When positioned between attractors, there is influence pushing and pulling on a system, like flowing water, pushing or pulling it toward a stable dynamical formation.   The differentiation of body cell development from basic stem cells is represented on an epigenetic landscape graph. The same stem cell can become many different types of cell systems, with distinct operational networks, which have different network autonomy. This diversification is an emergent form of order creation impelled by self-organizing criticality in the original stem cell network. The same stem cell can change its form into several different forms with unique new properties by re-self-organizing its archetypal network character. Attractors as potential dynamical trajectories

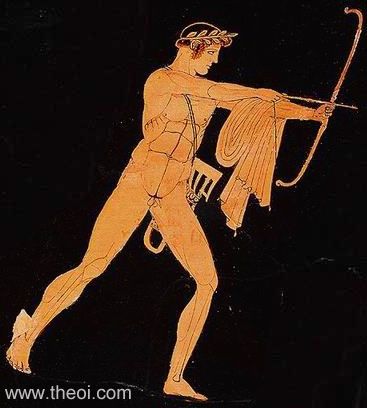

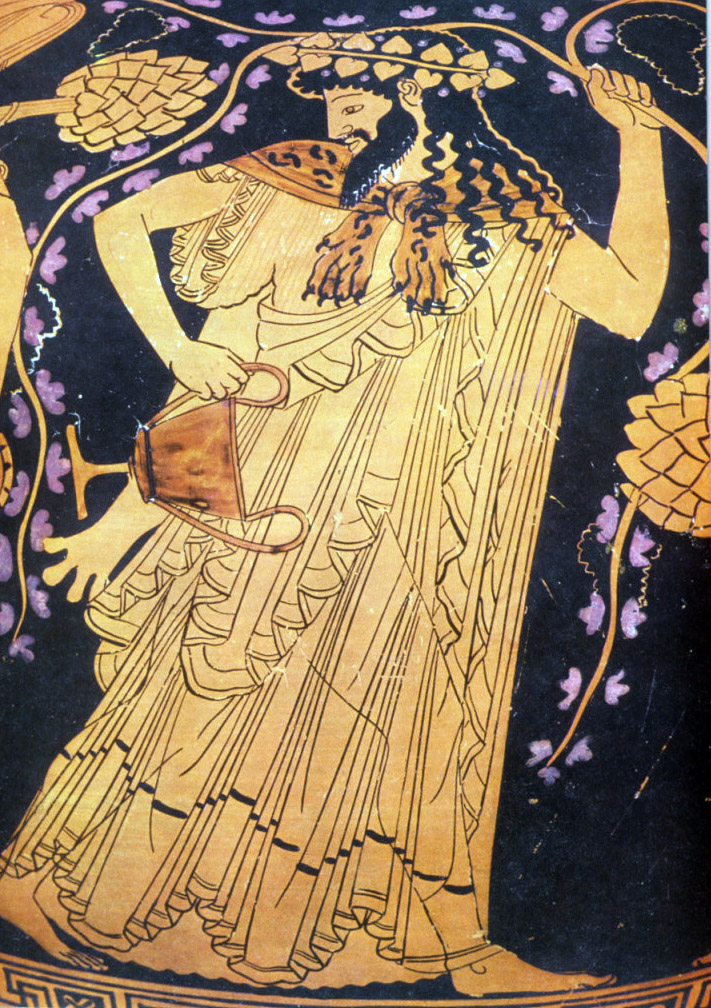

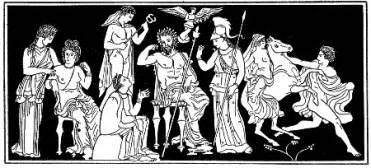

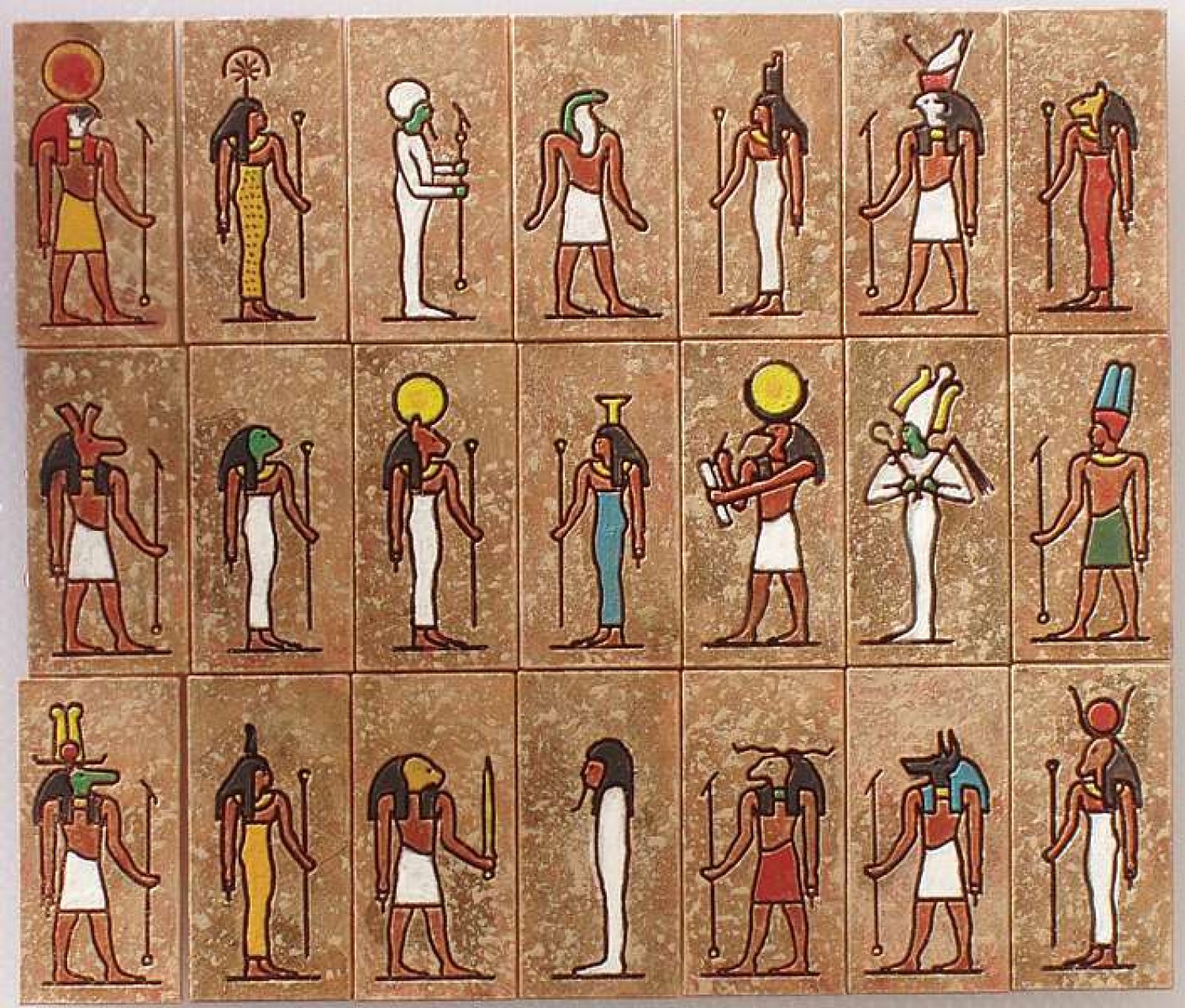

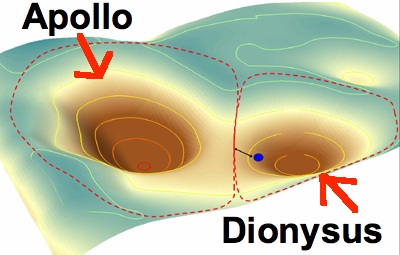

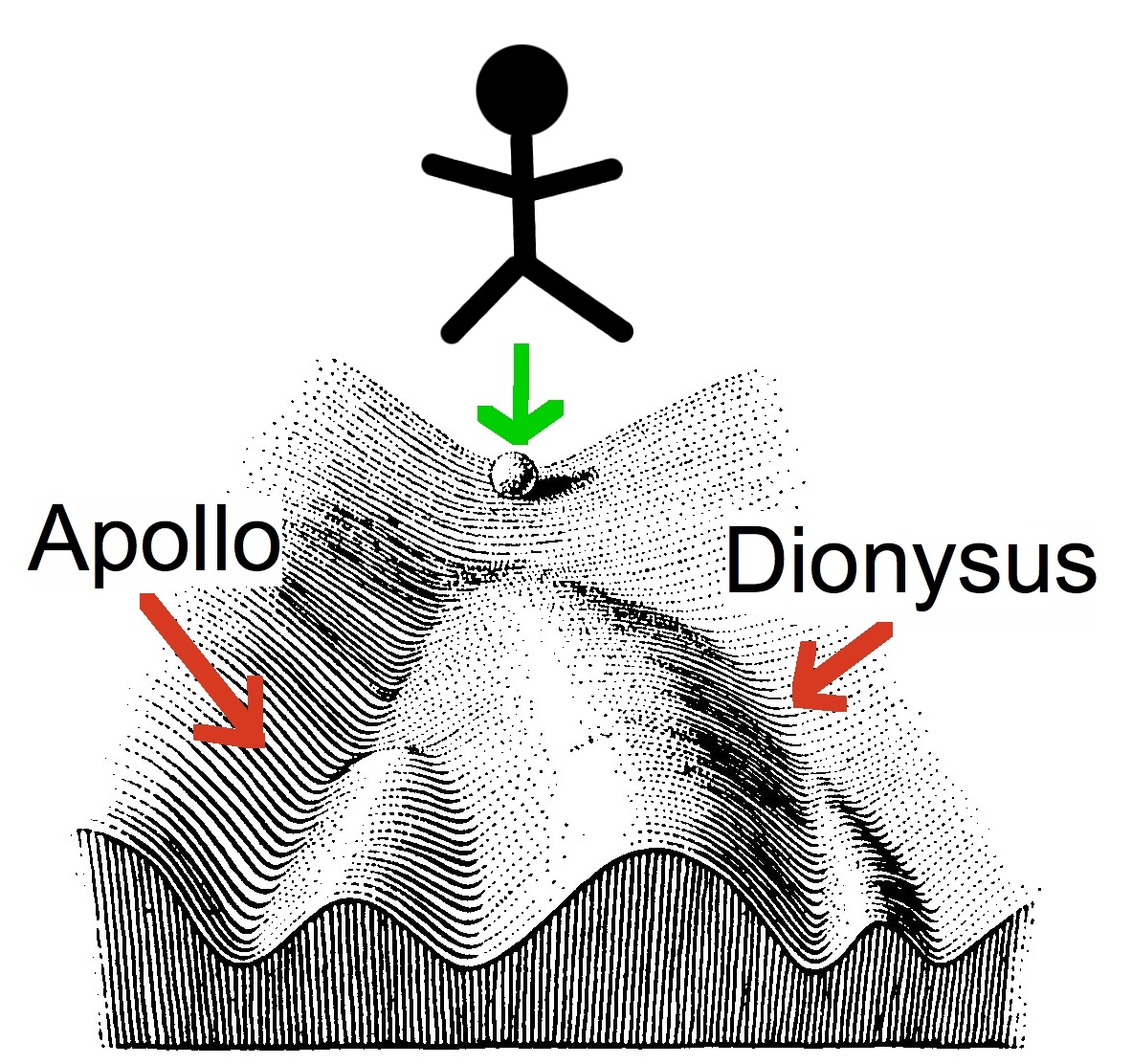

Cell differentiation viewed as attractor landscapes:   Though the graphs suggest that dynamical landscapes are static, this is not typically the case. The intensity and proximity of dynamical attractors varies in the unstable activity of complex system dynamics operating near the edge of chaos. Animation of these graphs helps grasp this aspect. Link to animated video of dynamical attractor landscape: The Con-spiracies of Spiritually Animating Dynamical Landscapes This concept of dynamical attractors forming landscapes of potential influence on the network operations of a complex system readily illustrates the mythological imagination's other world of diverse spiritual animators. Most cultural mythologies involve a diversity of spiritual animators of the world whose individual and collective traits involve paradoxical attributes and relationships. They are seldom portrayed as simple stereotypes. Instead, they tend to be complex characters with conflicting traits. The ancient Greek pantheon of gods and goddesses illustrates the variety of archetypal characters that compose the overall, archetypal meta-network of world animating agency. For the Greeks, the world was animated by hundreds of locally identified spirits as well as a more abstract pantheon of gods and goddesses, referred to as the Olympians--meaning those that dwelt in an upper world associated with Mt. Olympus. The society of dynamical attractors Pantheons of diversified gods that can represent attractor points in dynamical landscapes Greek: Egyptian:   Depending on the place and moment in time, some of these animators are more active in the emergent formation of order than others. Various networked relationships among them are portrayed in different traditional myths, suggesting ways they tend to become involved with each other--as symbols of network autonomy. These collective relationships can be thought of as "con-spiracies," as a "coming together" of particular spiritual or dynamical tendencies of order formation. In this way, mythic imagination provides a sense of how a particular "conspiracy" of dynamical attractors, under certain types of conditions, tends to generate characteristic emergent effects. These insights from the science of dynamical systems assist in understanding the diversity and multiplicity of spirits, gods, and goddesses that differentiate the archetypal character of network autonomy in myth's other world of ethereal influence on the ordinary one. With such correlations the potential of enhancing our capacity for "network vision" through a scientific mythology becomes evident. Abstract Spiritual Animators as Symbols of Archetypal Dynamical Attractors Relating mythic metaphors of spiritual animation to dynamical science helps reminds us that they are indeed not human, nor any sort of ordinary being. Despite being personified in myth, as agents who can can act like, or through, human persons, they have magically transformative powers, can metamorphically change their own forms, can appear anywhere and everywhere at once, and are often eternal. Thus they appear not to be limited by physical laws or chronological time. As abstract "forces of Nature," their capacity to generate such emergent order and transformative effects is portrayed as beyond willful human control. This metamorphic power and autonomy, along with the immaterial and eternal aspects of how they are portrayed, suggest they are like dynamical attractors: expressions of, or references for, traits of how order emerges from interdependent relationships, rather than the actual direct cause. Thus their existence is actually relative to their validity as symbolic expressions of how emergent order is created. As metaphors for archetypal characteristics of emergent network autonomy in complex systems, they model behaviors of such systems in a way similar to the graphically represented strange attractors of dynamical science. Personified spirits "stand for" the autonomous impetus that arises emergently in system networks. So there is an empirical basis for regarding "them" mysteriously creative "powers." The Paradoxically Conflicting, Co-Operating Archetypal Attractors of Polytheistic Pantheons The diverse psychological personalities of these animators associate with different ways that order emerges and network autonomy acts. Apollo is more rational and unemotional. He is a representation of the archetypal psychology of perceiving the world through mechanistic physics. His way of acting is represented by his association with the bow and arrow that can have effect remotely at a great distance. His brother Dionysus, in contrast, is an agent of ecstatic, embodied emotion. He is associated with wine and its transformative effects on ordinary consciousness. Yet as brothers, there is an indication that these contrasts are also interrelated. Taken together, they form a dynamical attractor landscape that exerts influence on embodied network souls, pulling them in different behavioral directions at once. Contrasting but related spiritual attractors

Rational

Apollo Ecstatic

Dionysus: Apollo & Dionysus as attractor landscape:   We can think of a person as a complex adaptive system,

continually generating its emergent network autonomy "at the edge of

chaos," as it interacts with the dynamical landscape around it. The

resulting interdependencies produce the emergence of particular types

of attractors, or the archetypal

tendencies of the network autonomy that is animating the system. That

unpredictable improvisation can be represented the system encountering

two contrasting gods as potential expressions of attractors on a

dynamical landscape. The

rational Apollo and the ecstatic, emotionally transformative

Dionysus are described as brothers in Greek mythology, suggesting their

contrasts have some intrinsic relationship in how order is emergently

created.

Eros:

Athena:As the human system "enters" this dynamic landscape, it is in an unstable position that might jump to manifesting either one of these attractors/gods. That potential is represented by two possible trajectories for the behavior of the system's network autonomy. As the network of the human mind system interacts with the two different archetypally animating attractors, it can choose, or be pulled, into one dynamical behavior more than the other.   Combining the scientific metaphors of dynamical attractors and landscapes with the myth's metaphors of spiritually animating agency reinforces how both stand for what cannot ultimately be directly described and explained. At the same time, the correlation enhances how both modes of representing emergent network dynamics convey the effects of complexity's mysterious self-organizing creation of order. The Dynamical Landscapes of Spiritual Pantheons This basic notion of how spiritual animators can form an attractor landscape expands to consideration of the paradoxically diversified figures of traditional mythological pantheons. Staying with the ancient Greeks, the god of relationship, Eros, is winged and musical. But he is regarded in Greek mythology as a dubious influence who haunts thresholds where he can seductively prompt sudden transformations in network behaviors, resulting in great disruption. His archetypal dynamics can bring intimacy and harmony, but also trouble and conflict. The goddess Athena is a aggressive female warrior born from the head of her father Zeus. Yet she is also associated with the civilizing dynamics of lawful social order.   The god or war, Ares, embodies the emergent properties of battle. Yet promiscuous goddess of love, Aphrodite, who has attributes as varied as she who makes children laugh and she who walks on the graves of men, favors Ares as the most attractive lover. Curiously, she is married to the least attractive of the Olypians, the crippled Haphaestus, who is a god of craft and technology. Ares and

Aphrodite:

Hephaestus:

In the Hindu pantheon, Shiva is a male identified power of both creation and destruction, indicating that these aspects of emergence and network autonomy are intrinsically interdependent. Yet despite his potency, he cannot dominate Kali, a goddess of feminine associated destructive fury. Shiva's consort is the loving, peaceful Parvati. In a fit of jealous rage, Shiva beheads their son, Ganesha. But he replaces the head with that of an elephant and Ganesha becomes, among other aspects, an animator of good fortune and jovial behavior. Shiva and Parvati's contrasts are also fused in a single hermaphorditic form, again indicating the archetypal complexity interdependency among aspects of emergent network animation. Shivas diverse character

Shiva:

Kali over Shiva:

Shiva and

Parvati: Shiva/Parvati:    These examples of how mythic imagination personifies network autonomy's capacity to "act" in animating the things and events of our ordinary world, the traits of complex network structure and dynamics are clearly evident. Events emerge from simultaneous, synergistic interactions among distributed networks of feedback. Relationships and events that we ordinarily perceive as predictable or have hierarchical order are ever influenced by abstract, intentional, but unpredictable impetus. The turbulence of spiritual characters Interactive turbulence of dynamical landscape of archeytpal animators:    What we see as hierarchy is more likely self-organizing interdependency of network agents influenced by archetypal/spiritual animators:    Again, it is useful to think of these pantheons of many gods and goddesses as a elaborate landscape of diverse dynamical attractors that is continually fluctuating and re-arranging as they interact in various ways. But the stories of myth do indicate there are some characteristic, if not predictable, traits to the ways these ethereal forces shape the things and events of the ordinary world by influencing the behaviors of its complex systems' network autonomies. Other Symbolic Dynamical Landscapes The mythic imagination takes many forms, extending from mythologies of gods and goddesses to the symbolic traditions such as the Tarot, Astrology, and Alchemy. The latter provide a kind of library of symbols and some principles that allow networks of relationship between these to be revealed, relative to partiular times and events. Symbolic Libraries of Network Animation